NYMZA Aeros – Charles Dellschau and The Secret Airships of the 1850s

.jpg)

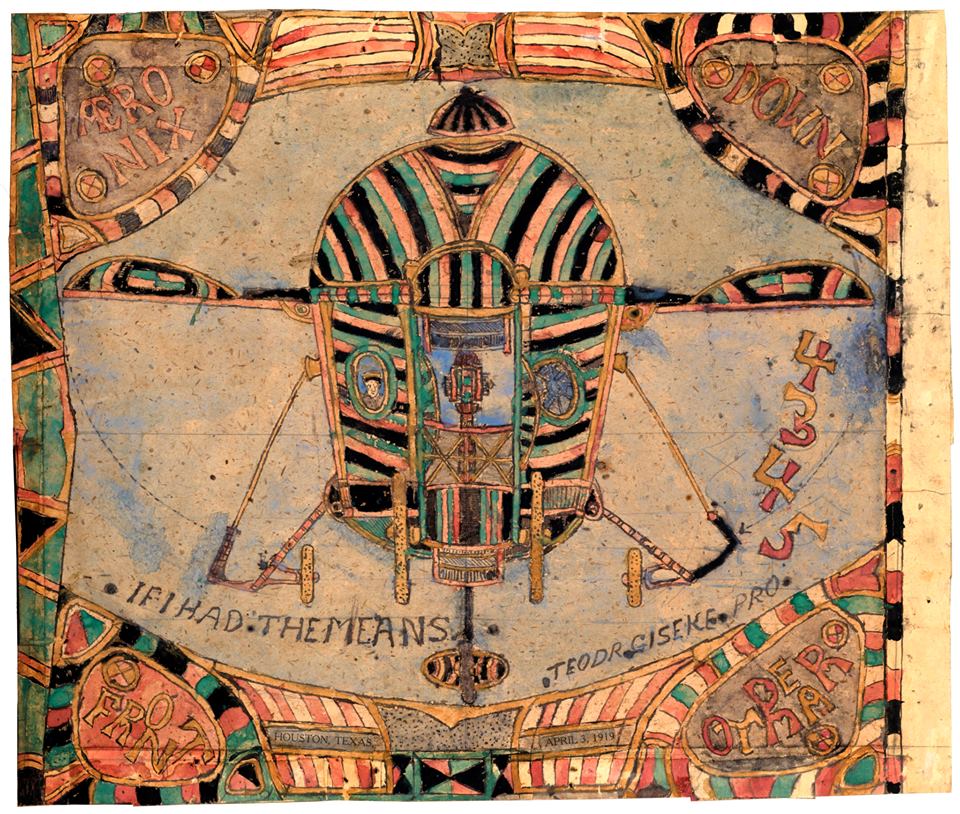

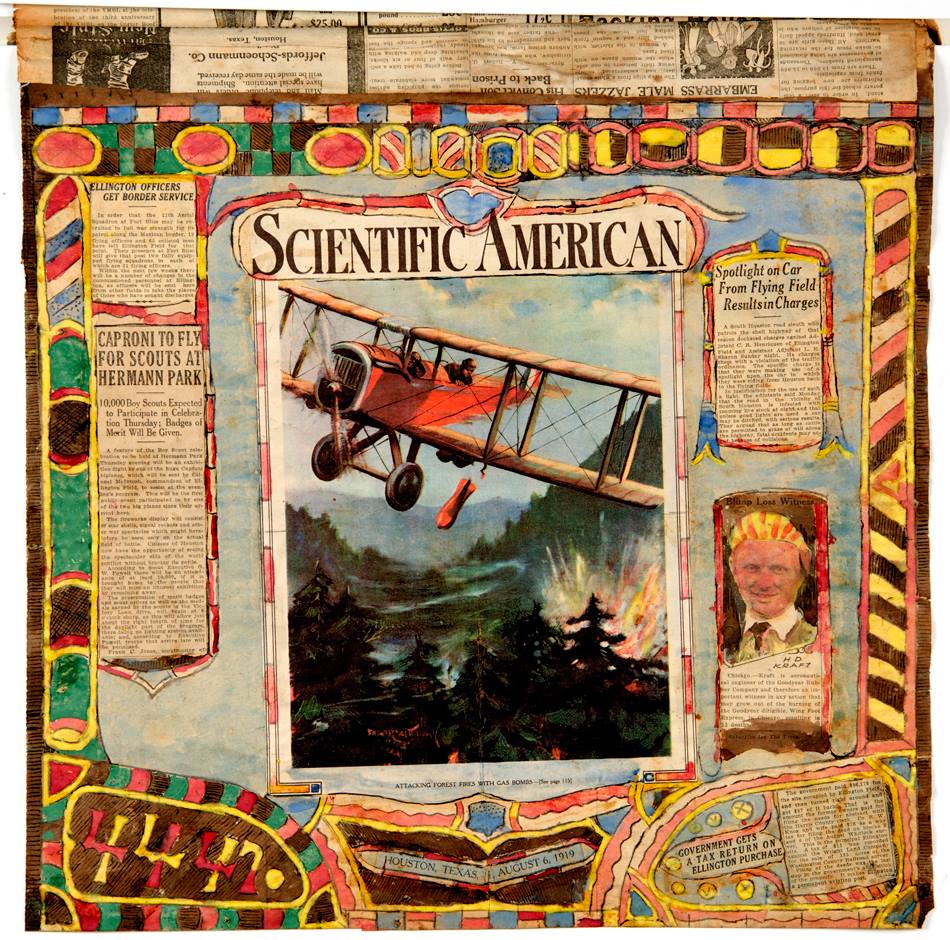

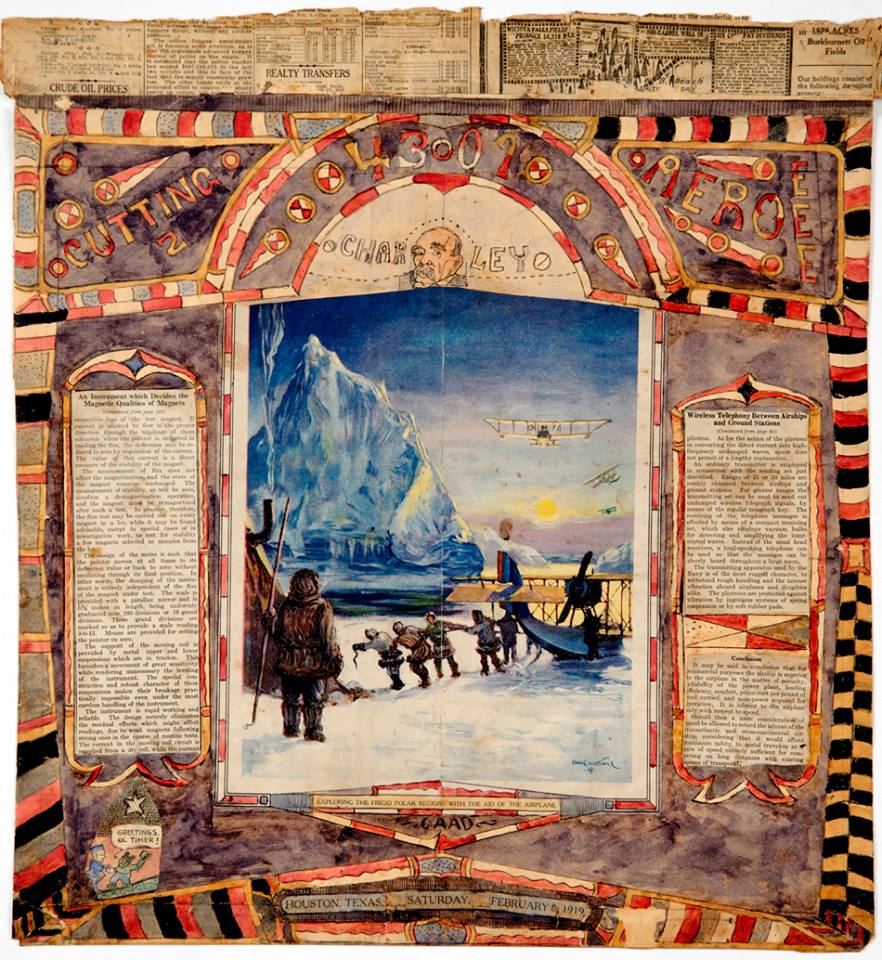

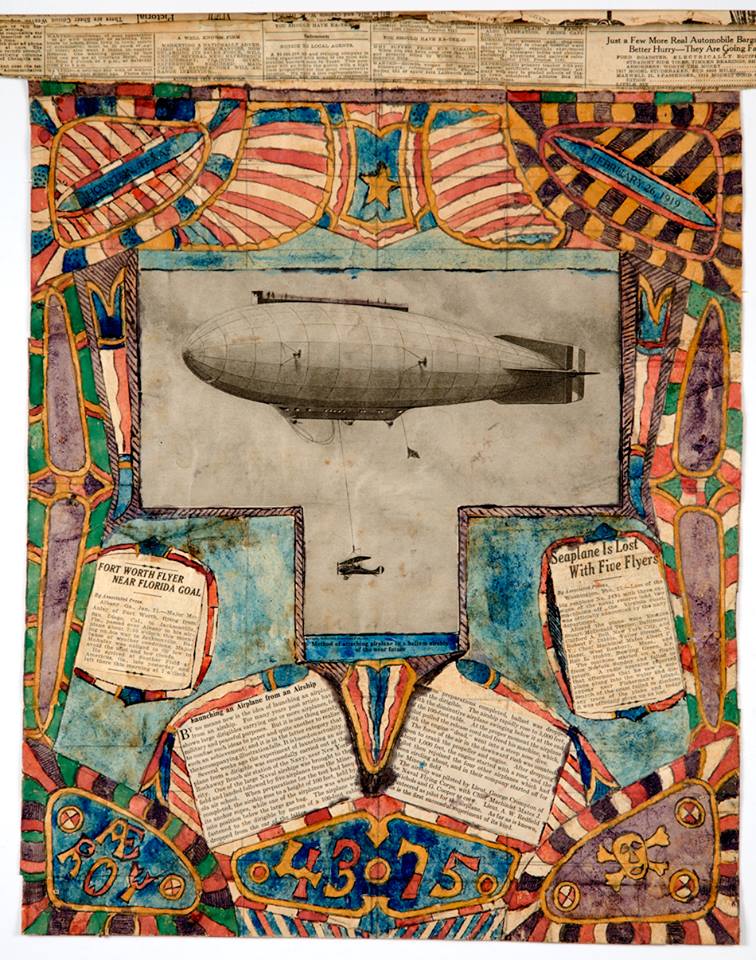

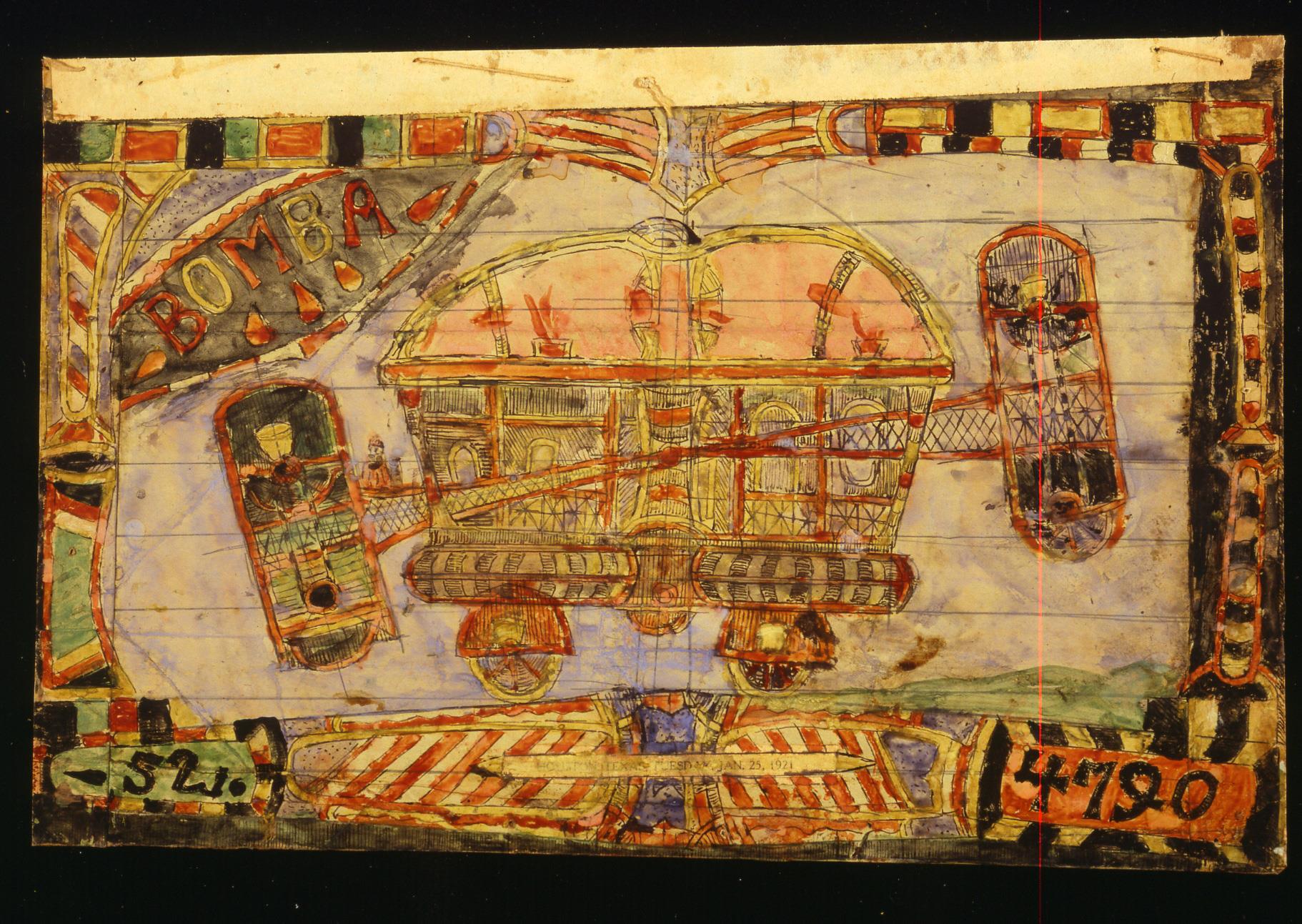

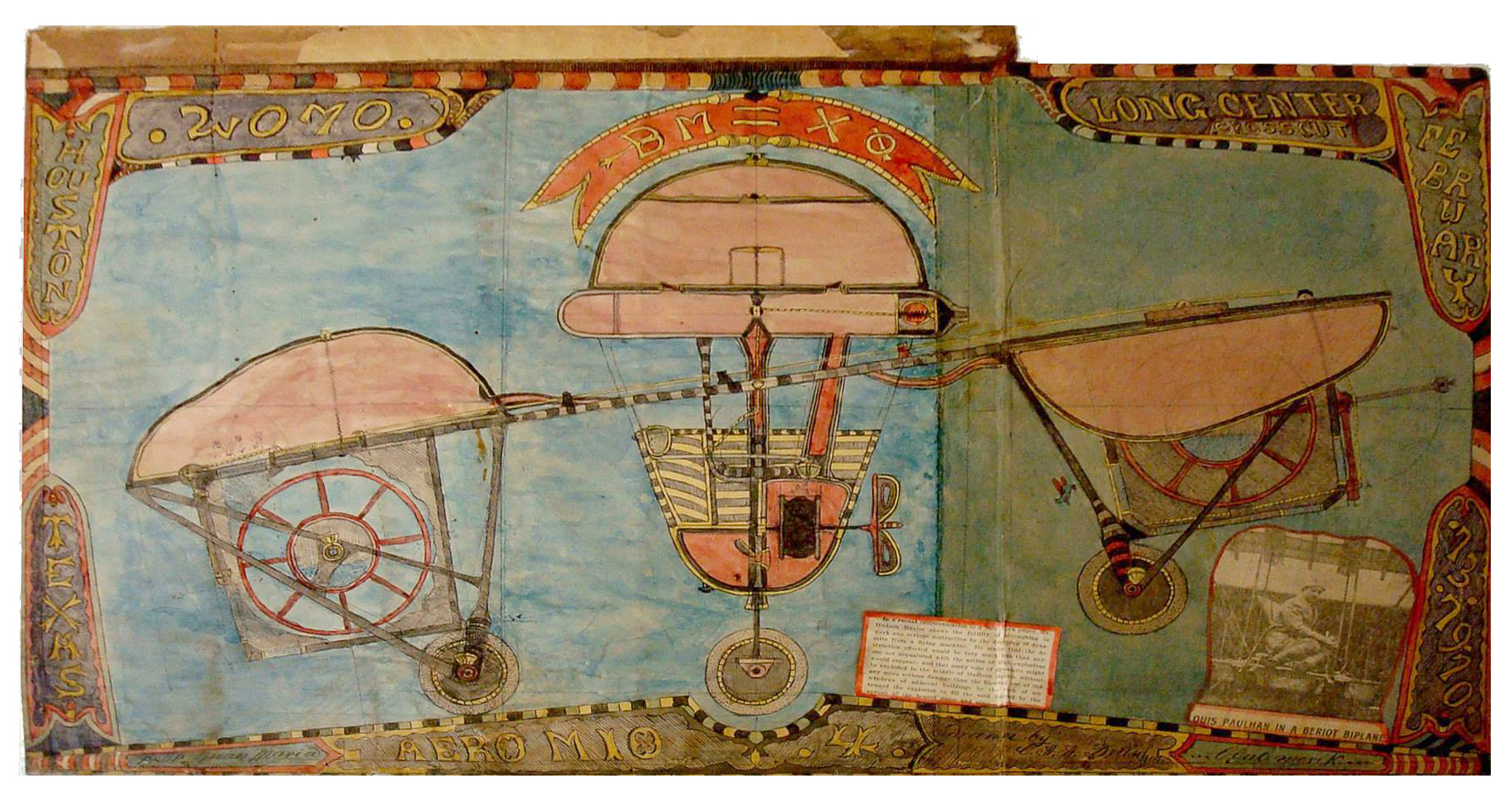

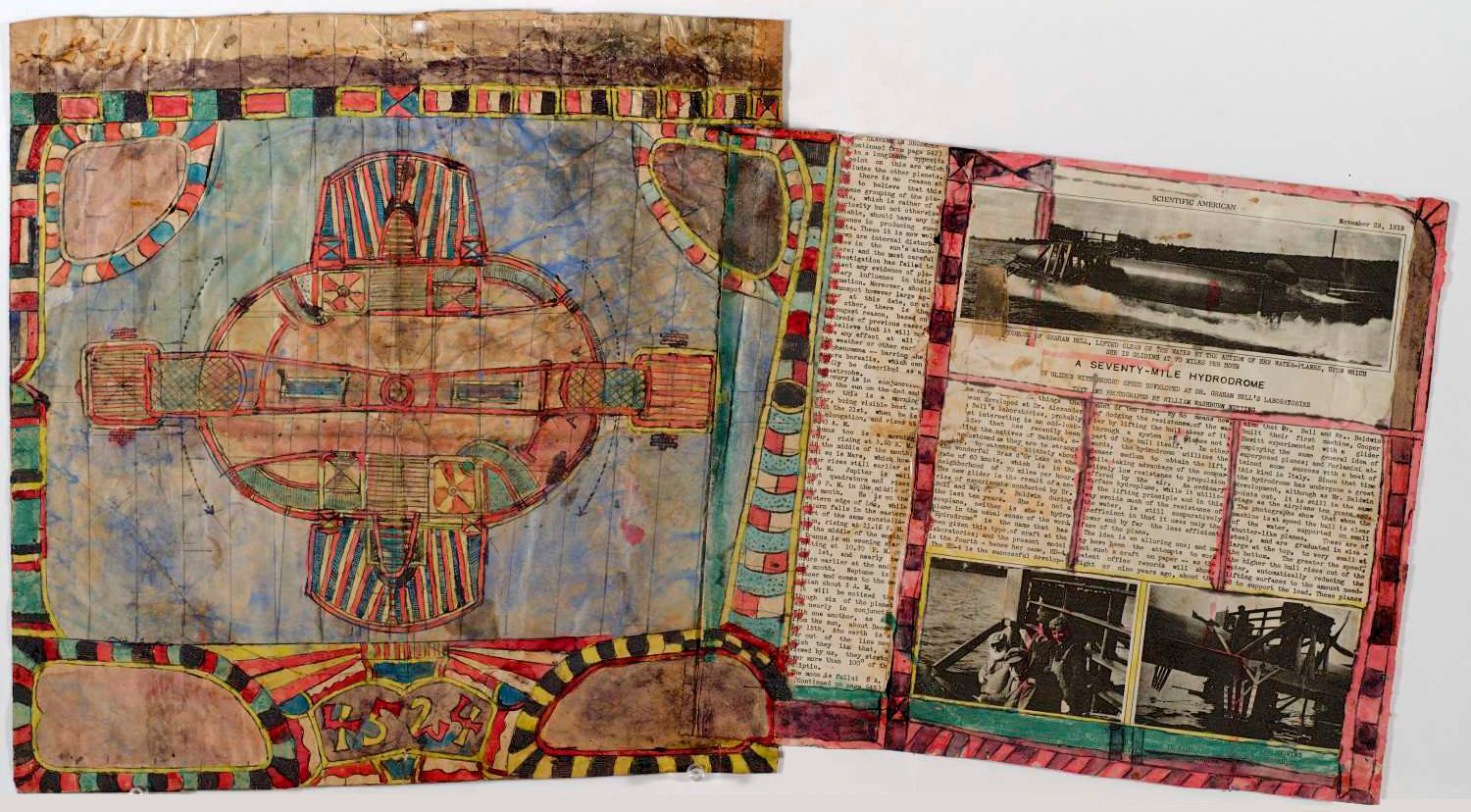

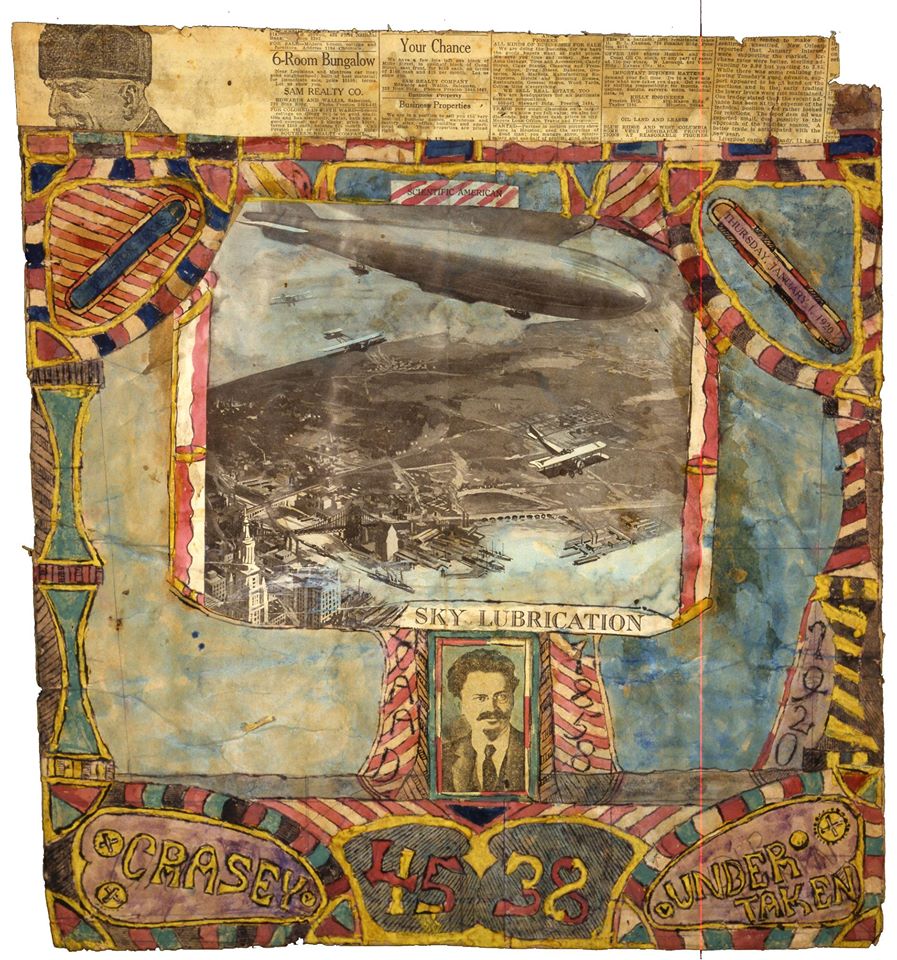

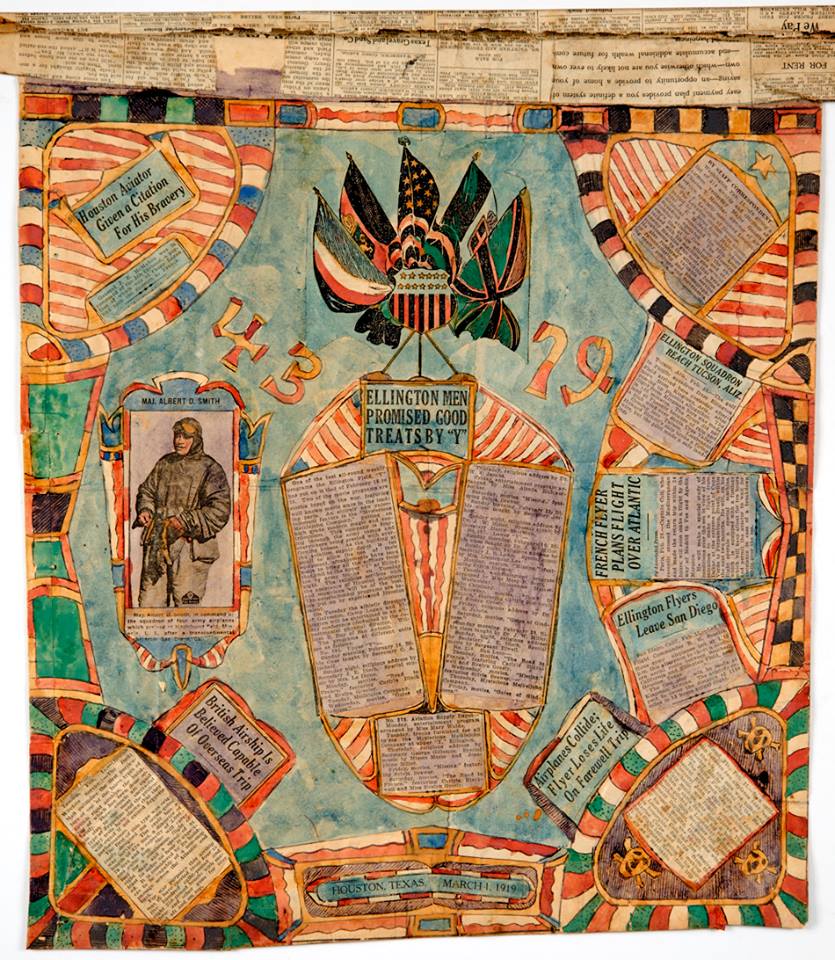

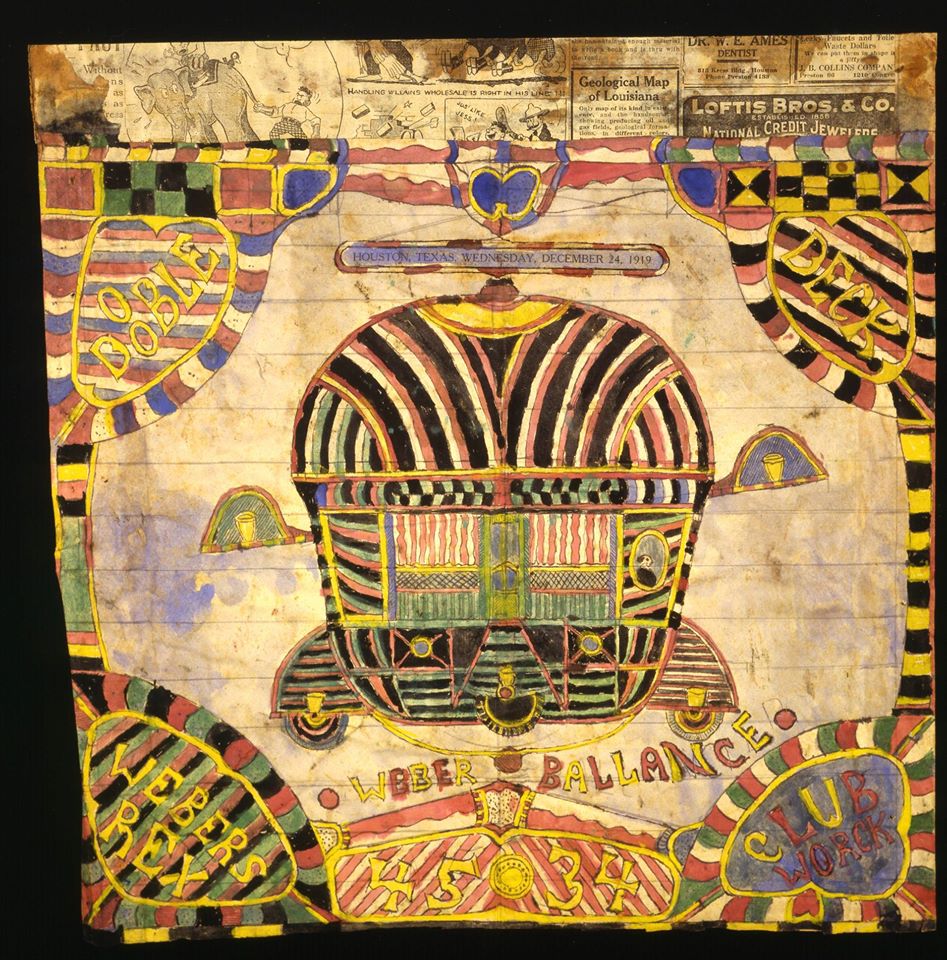

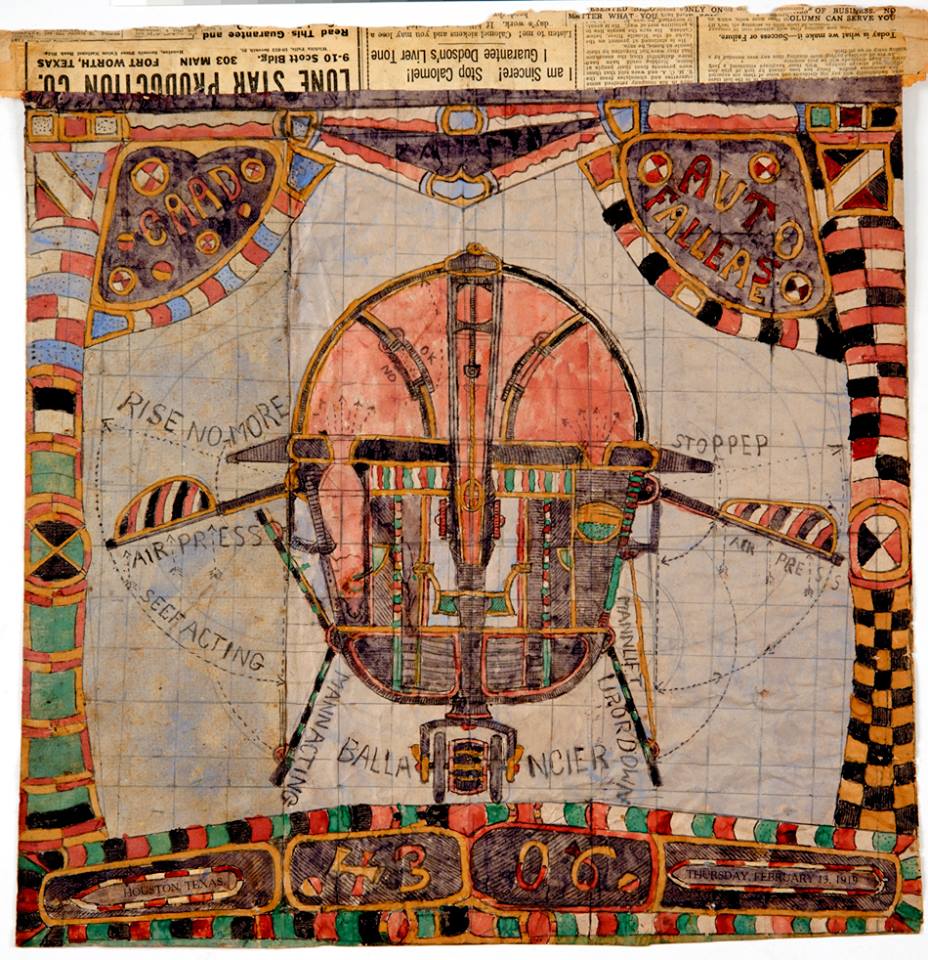

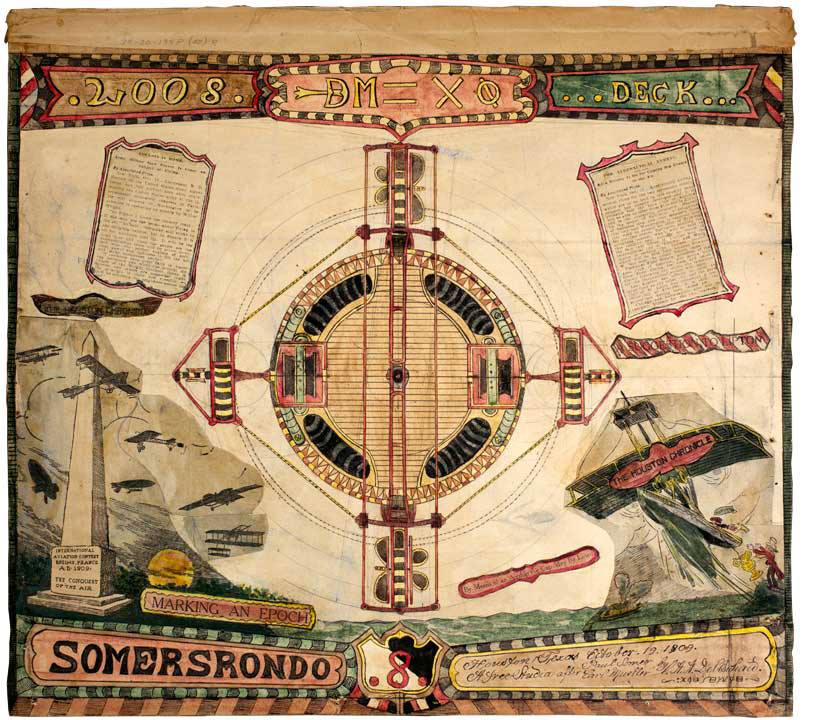

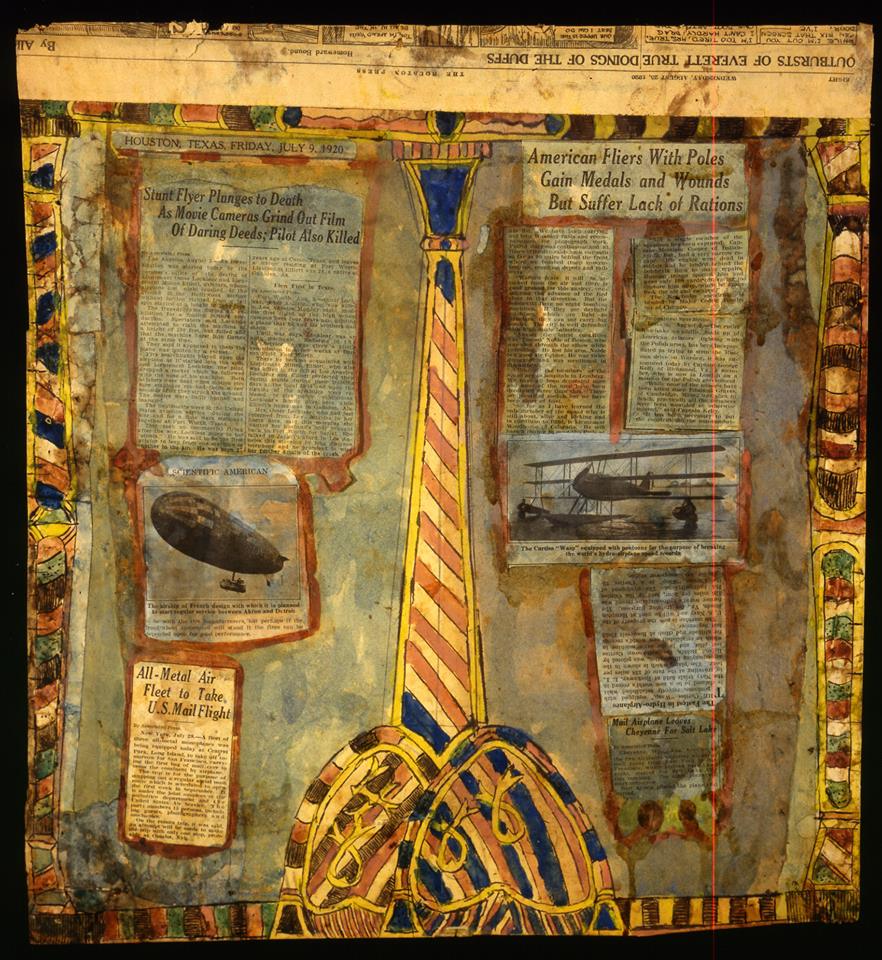

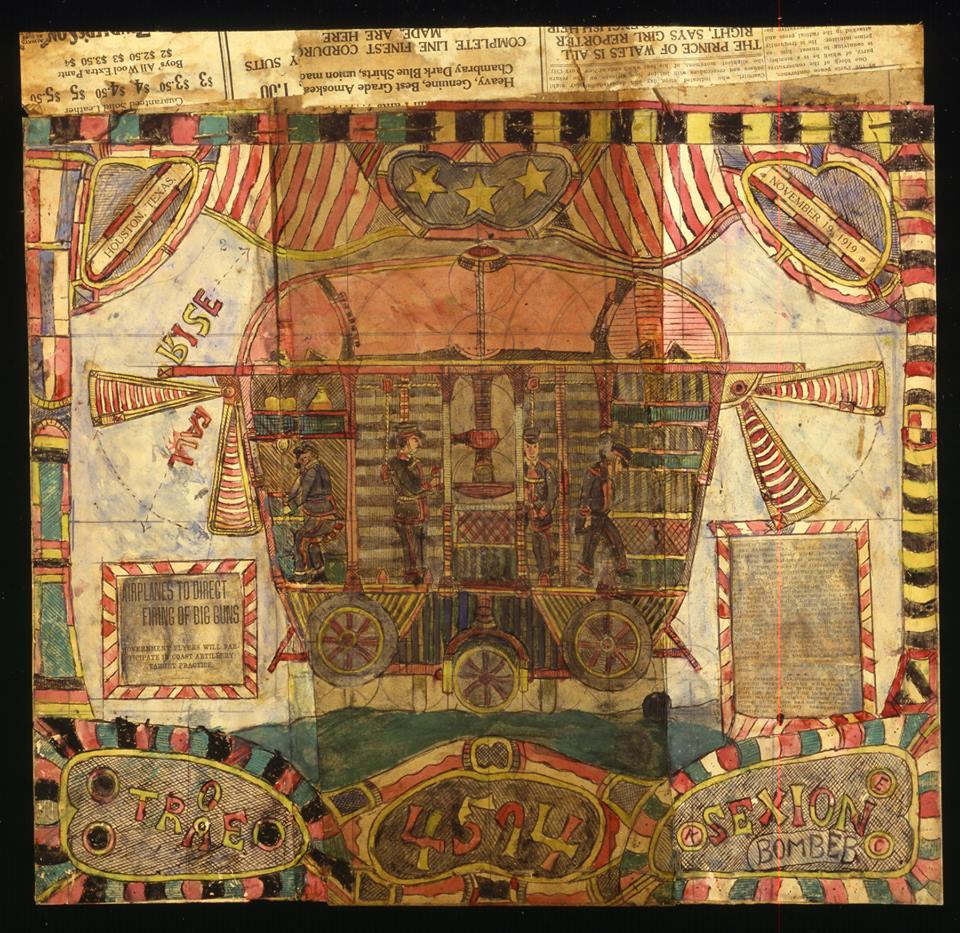

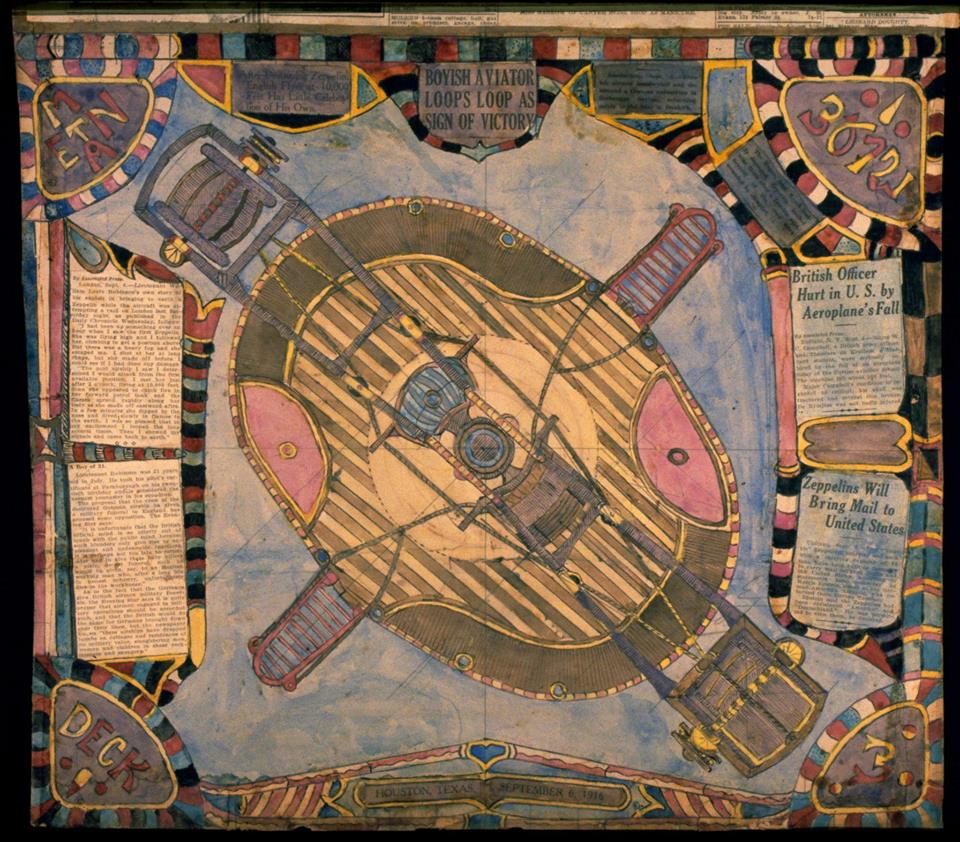

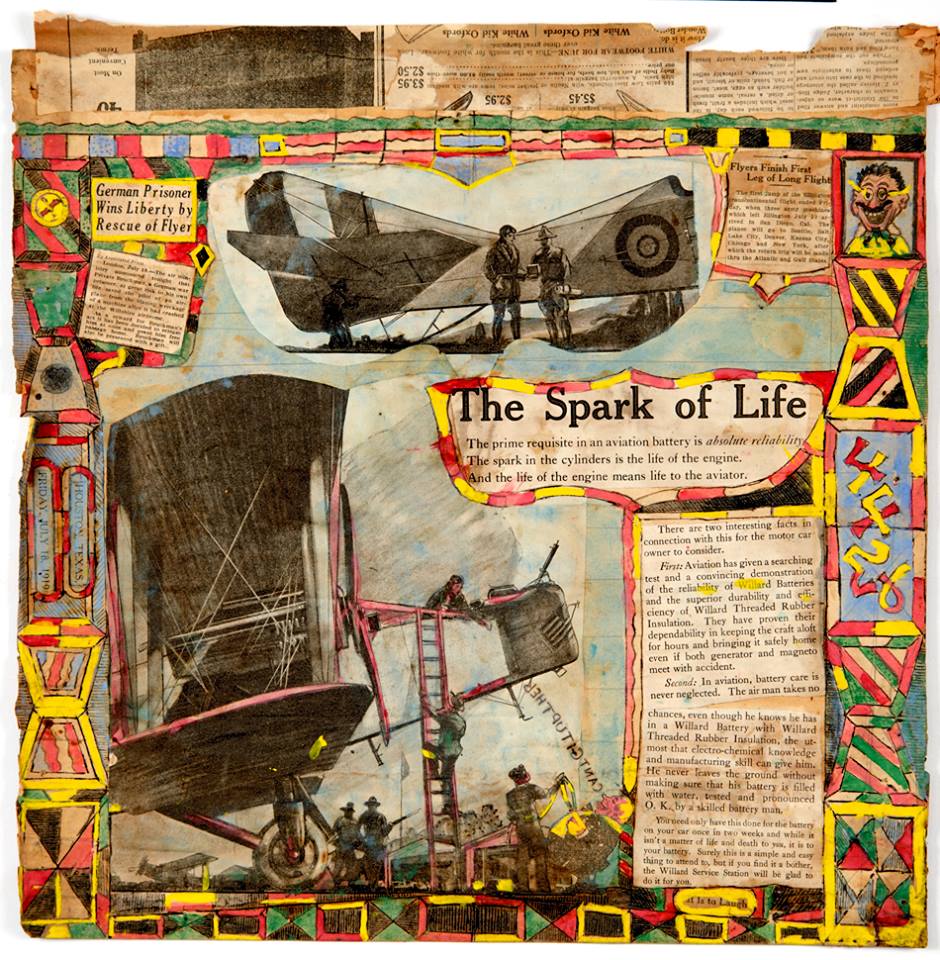

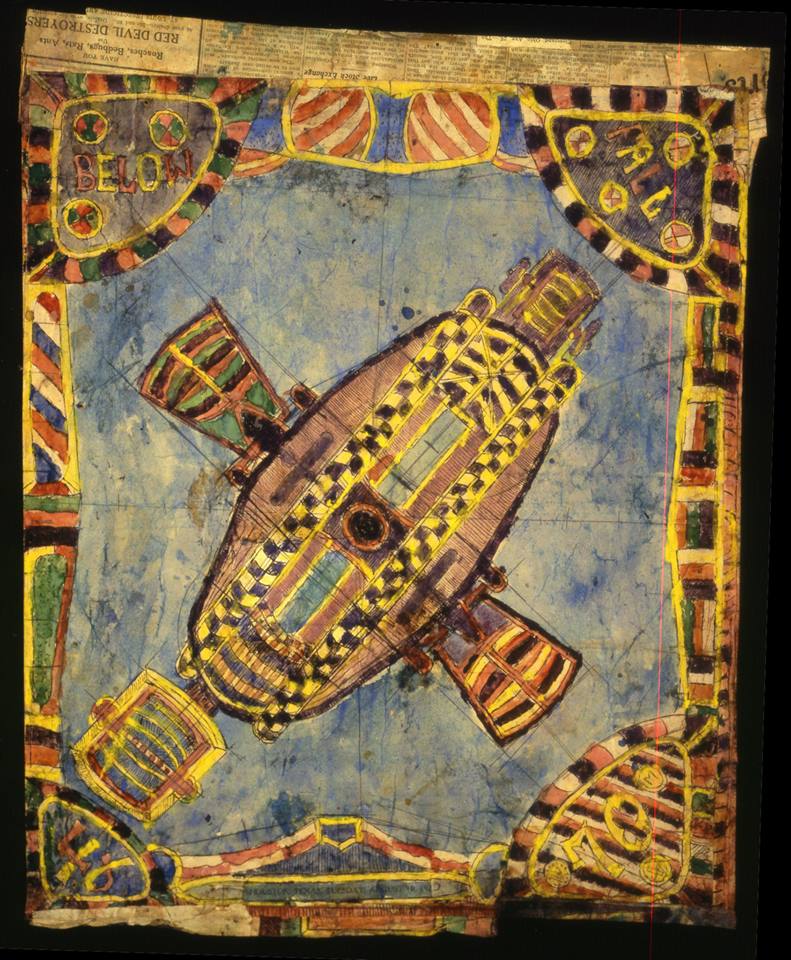

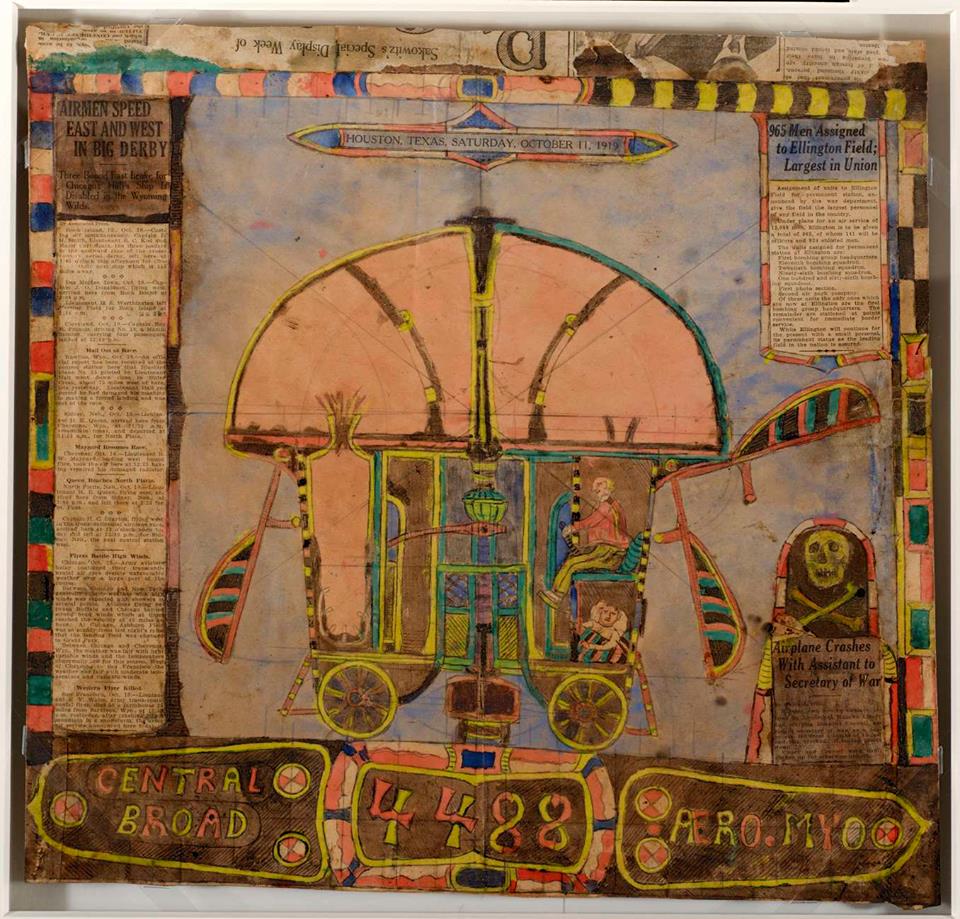

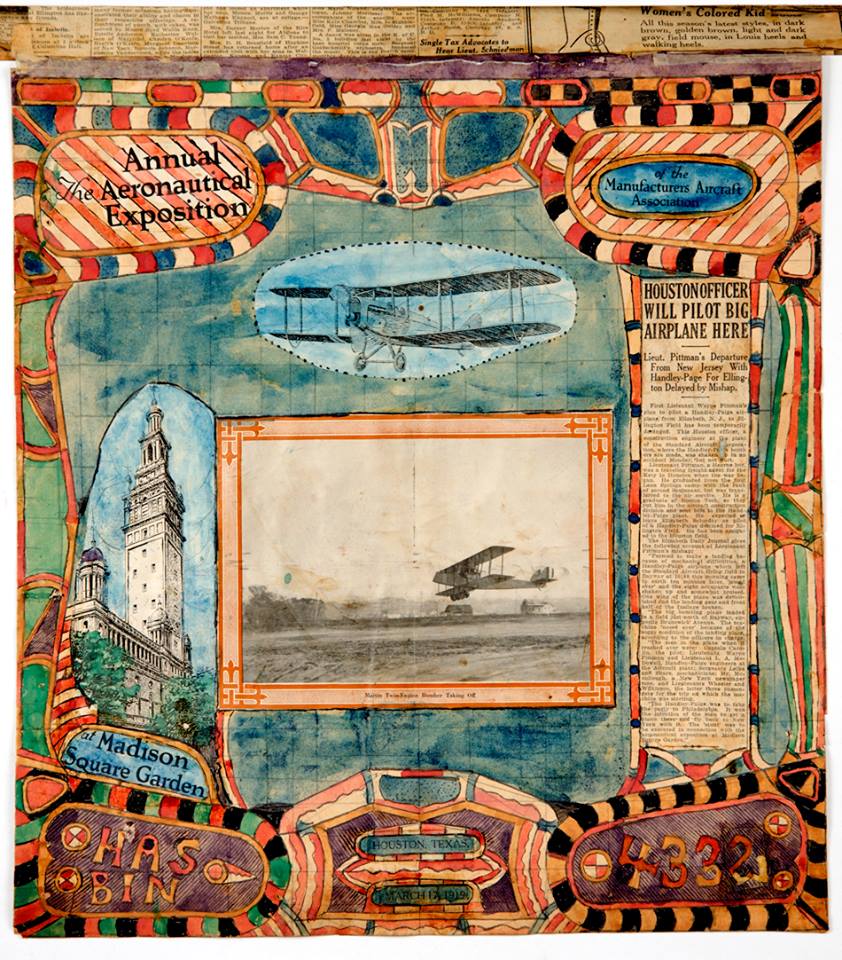

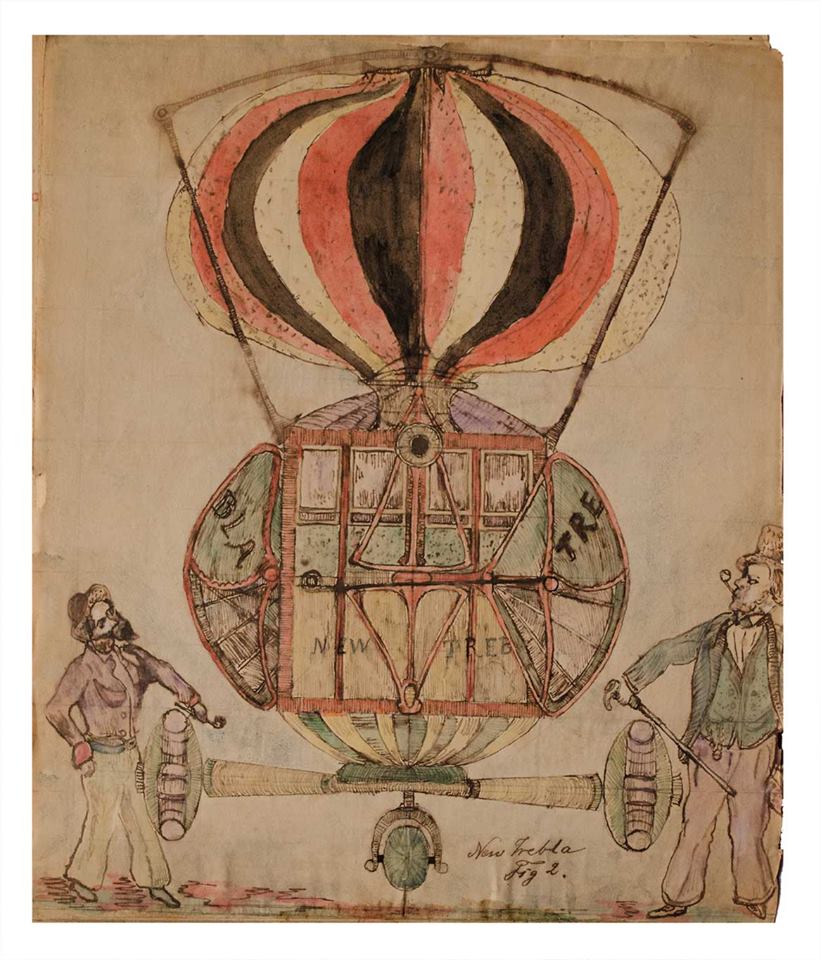

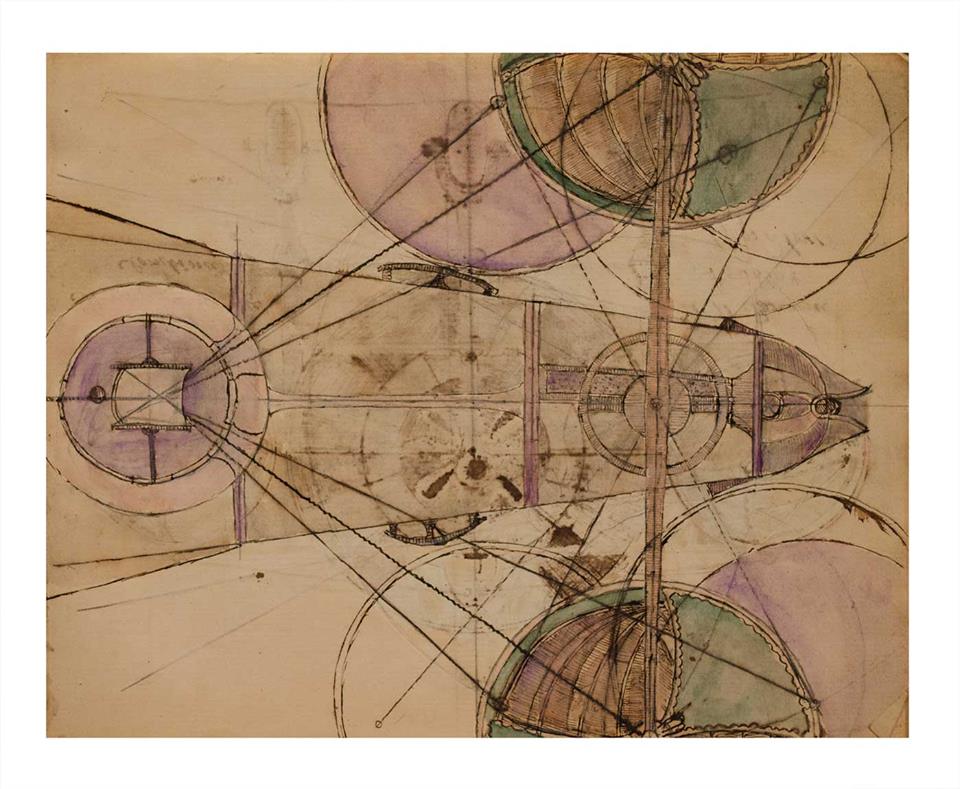

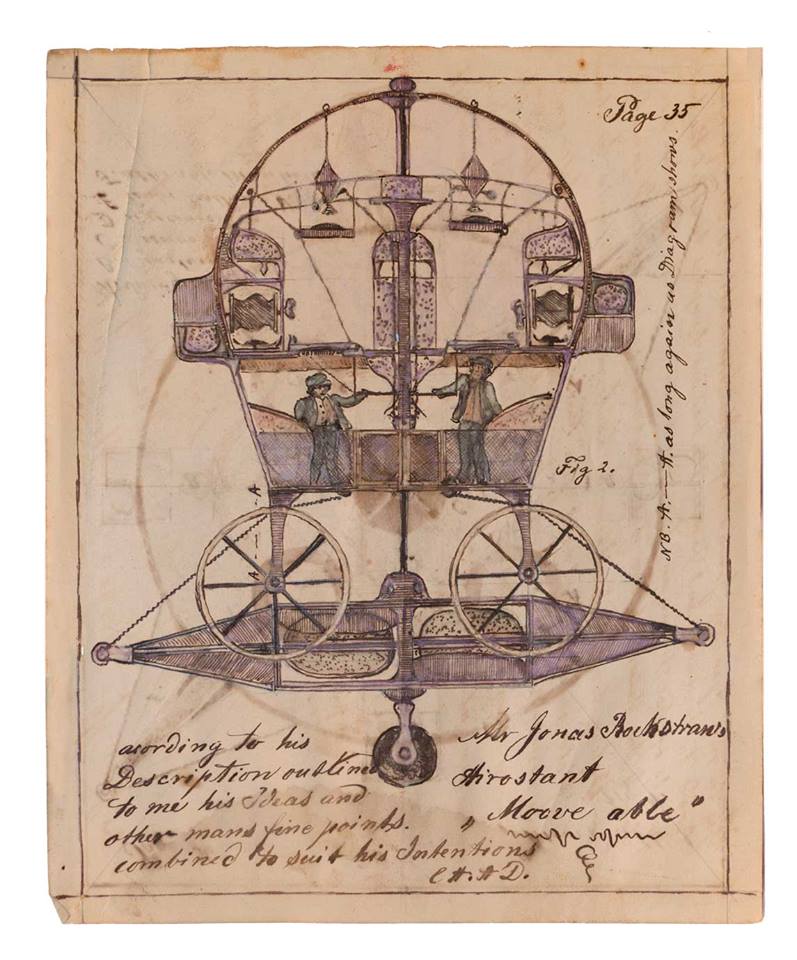

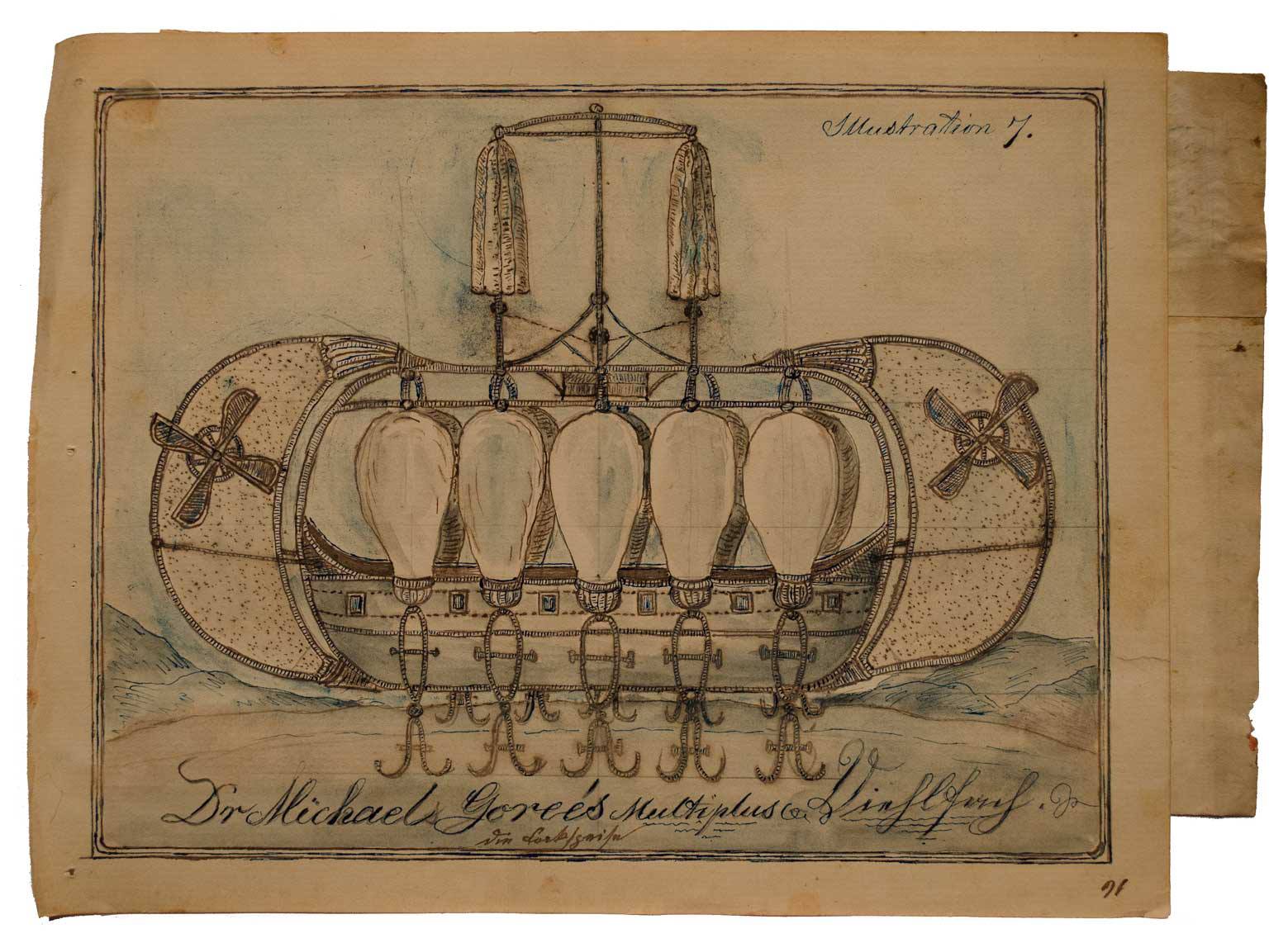

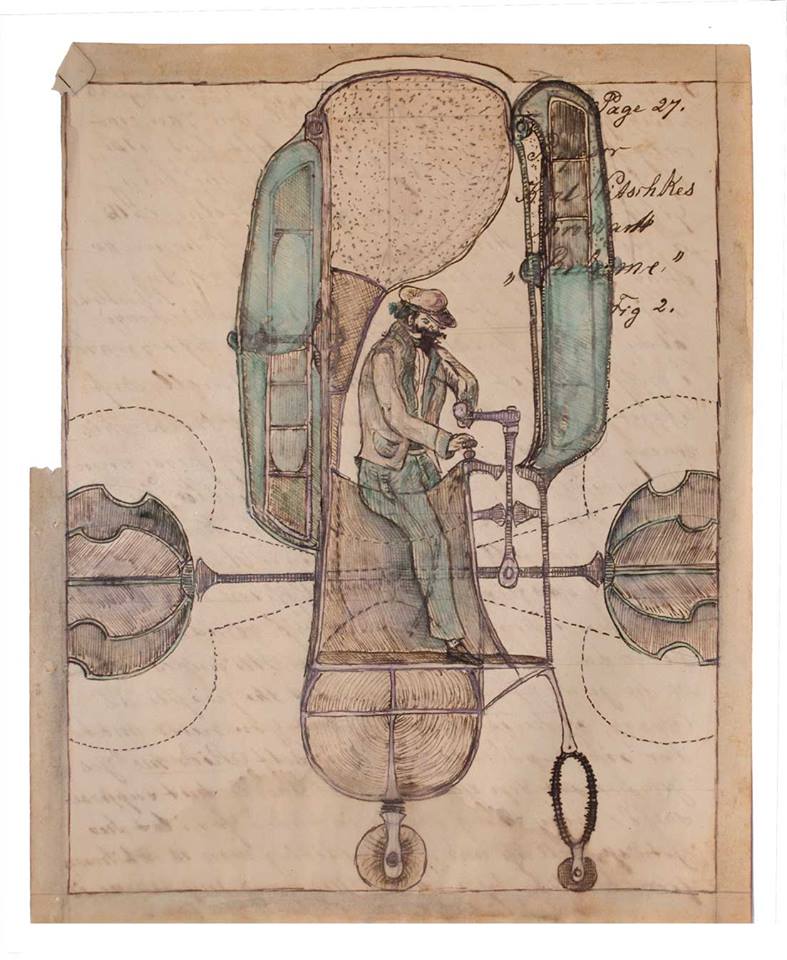

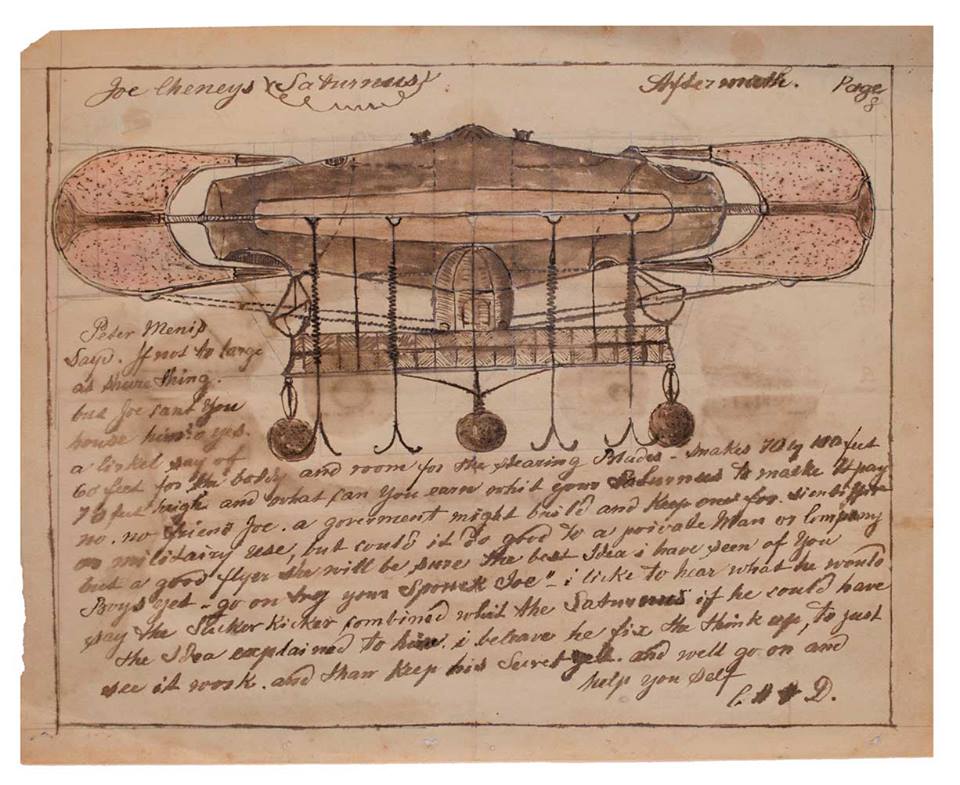

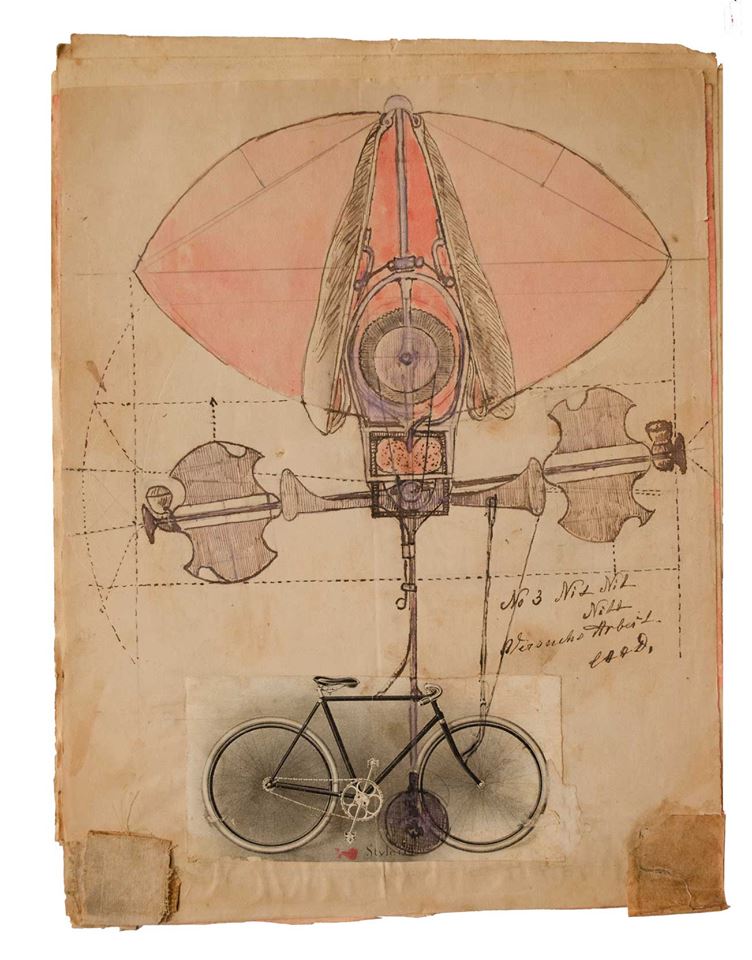

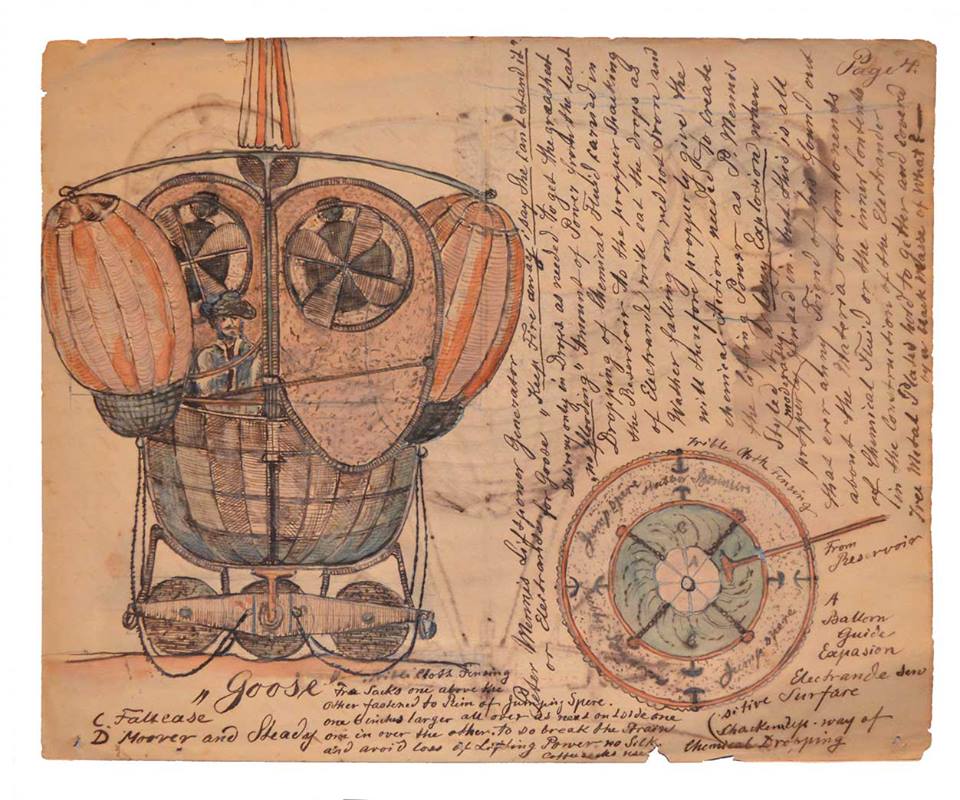

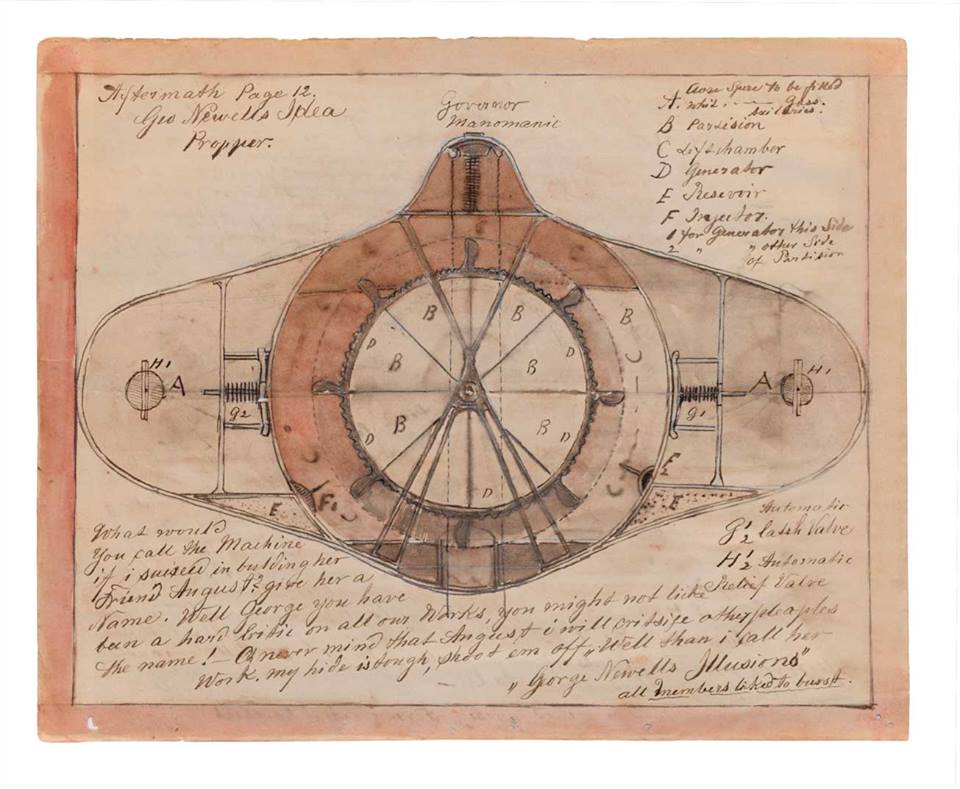

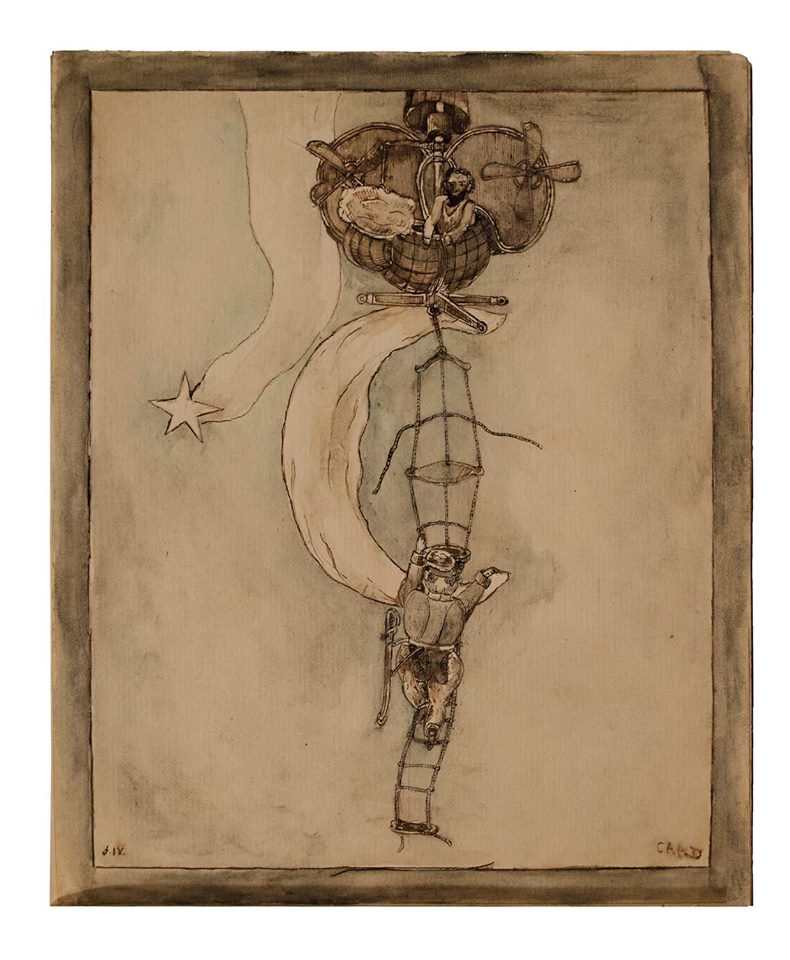

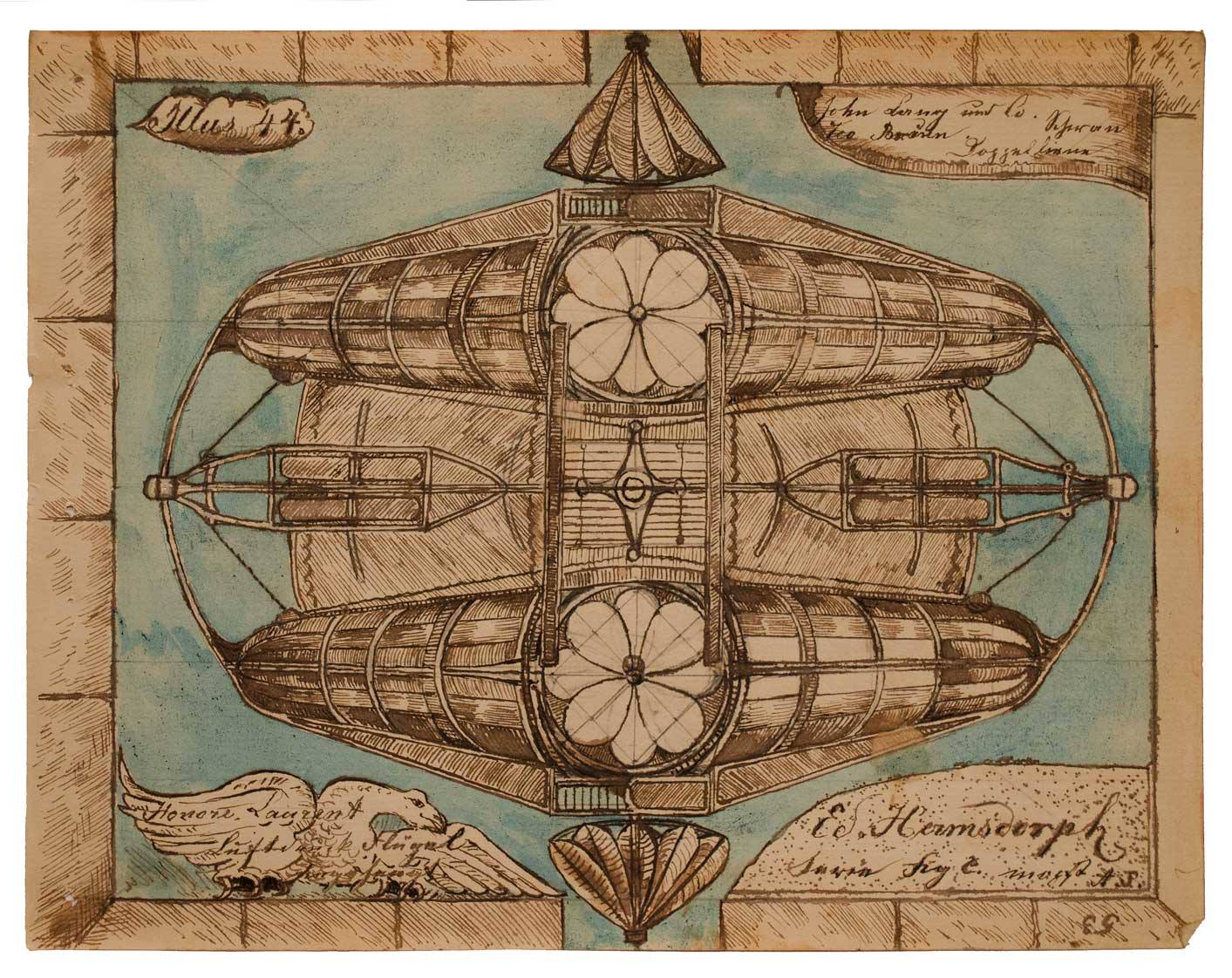

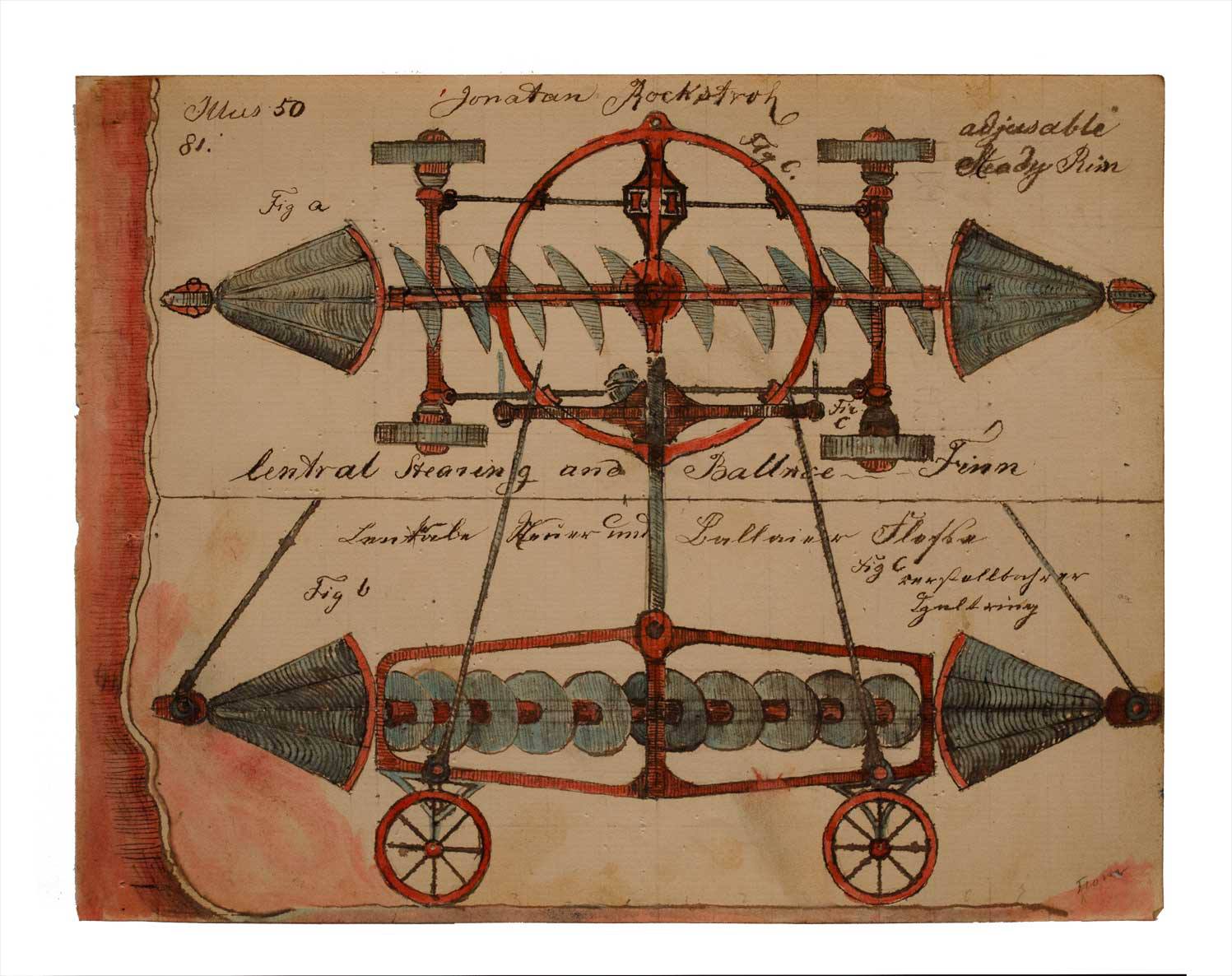

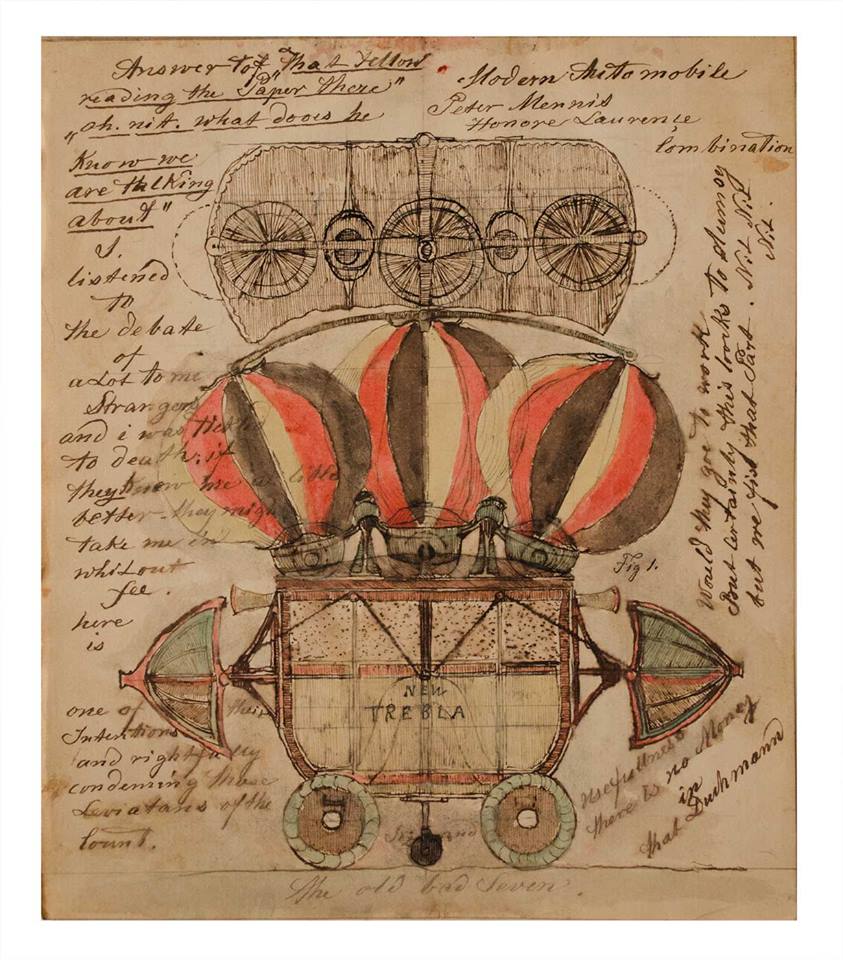

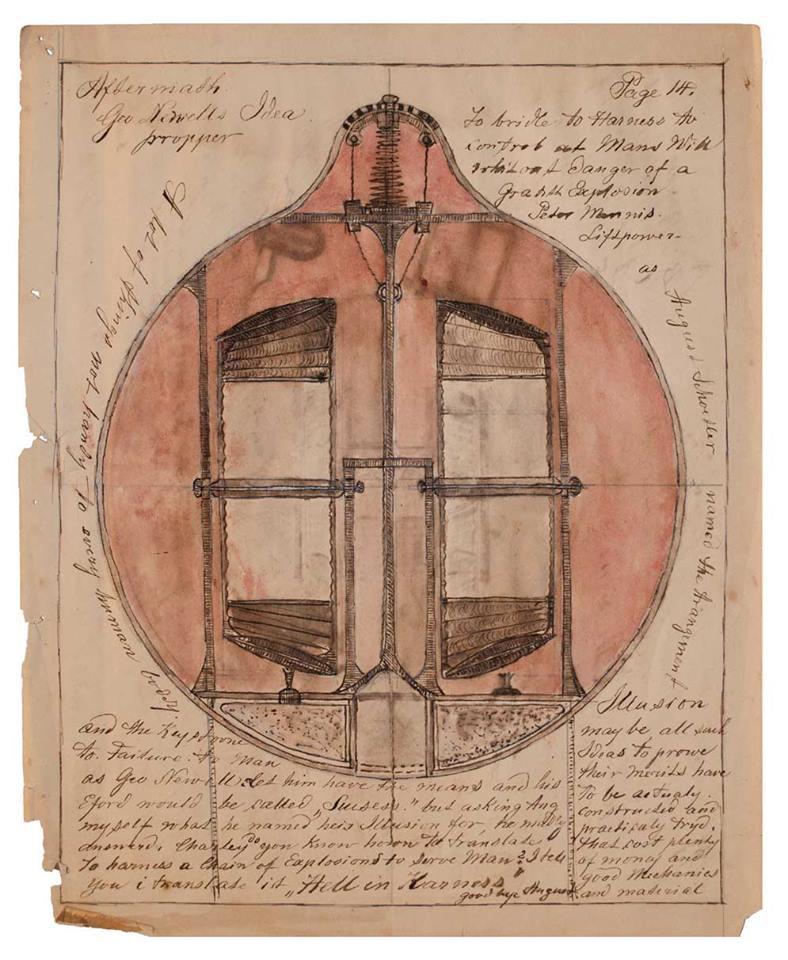

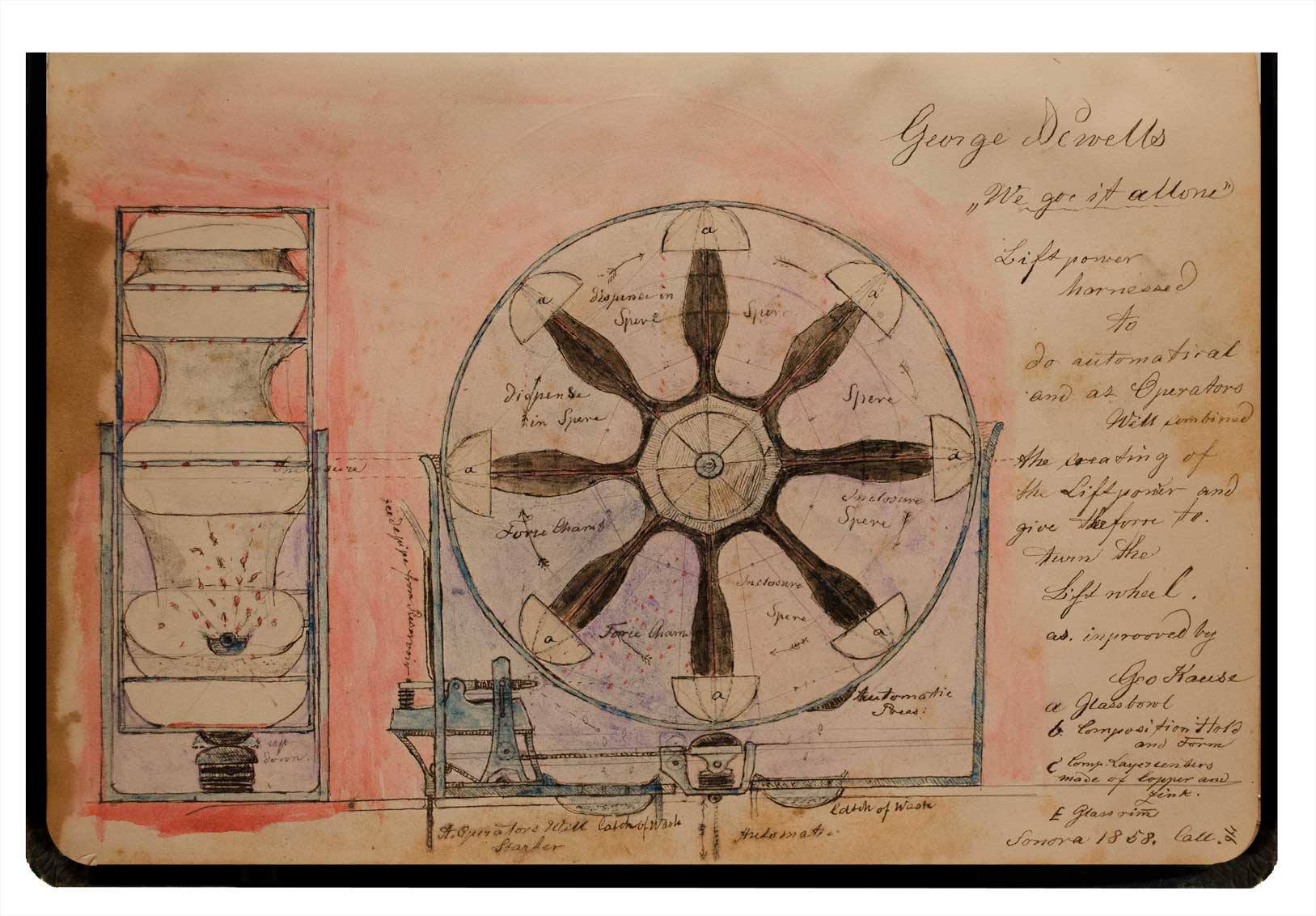

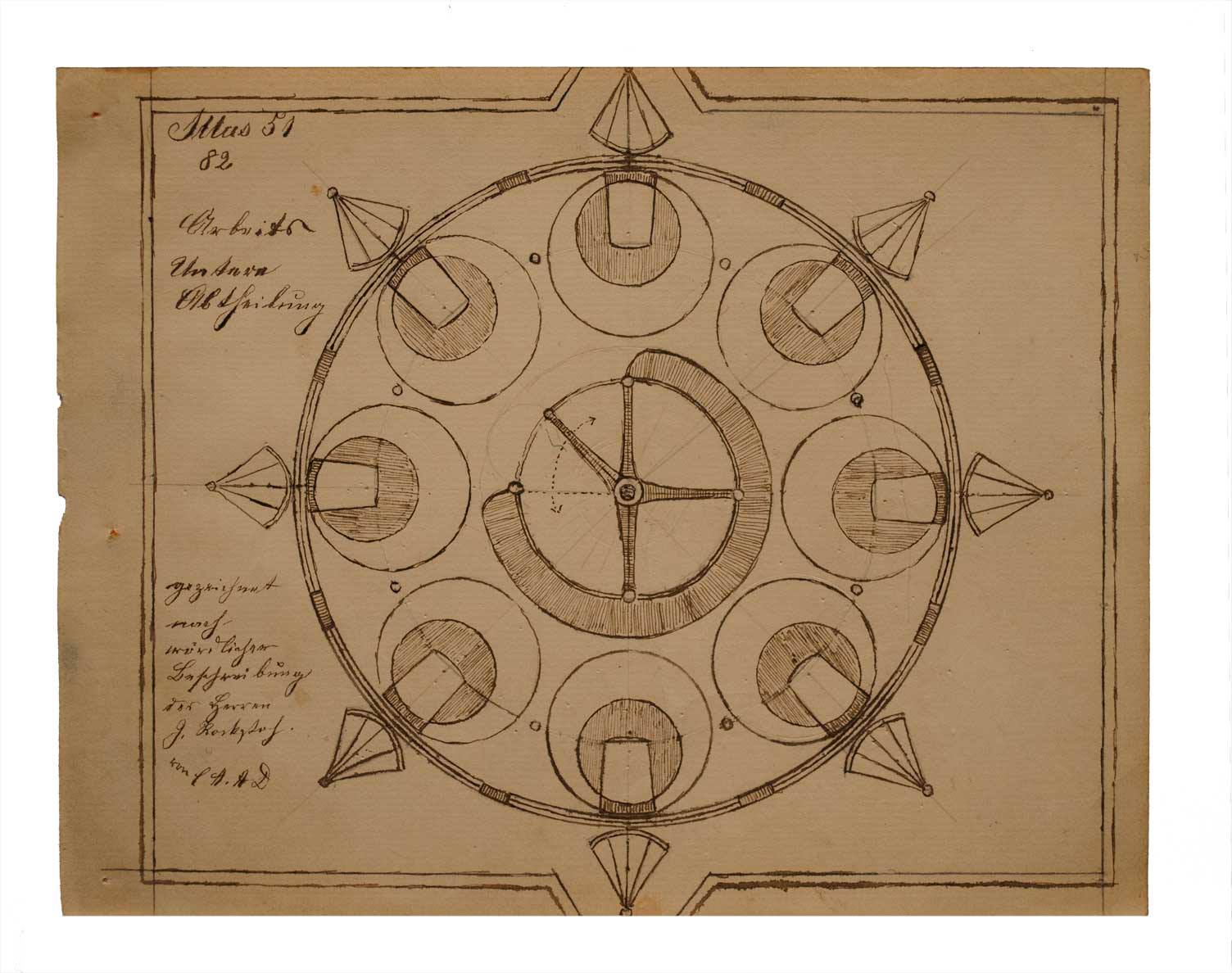

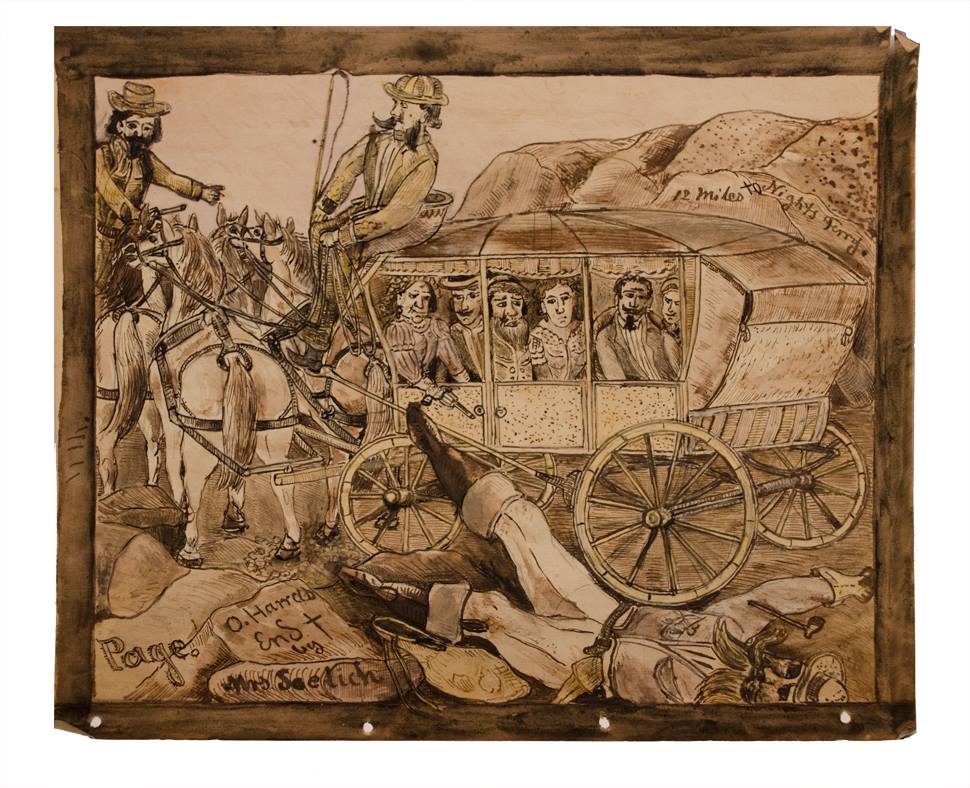

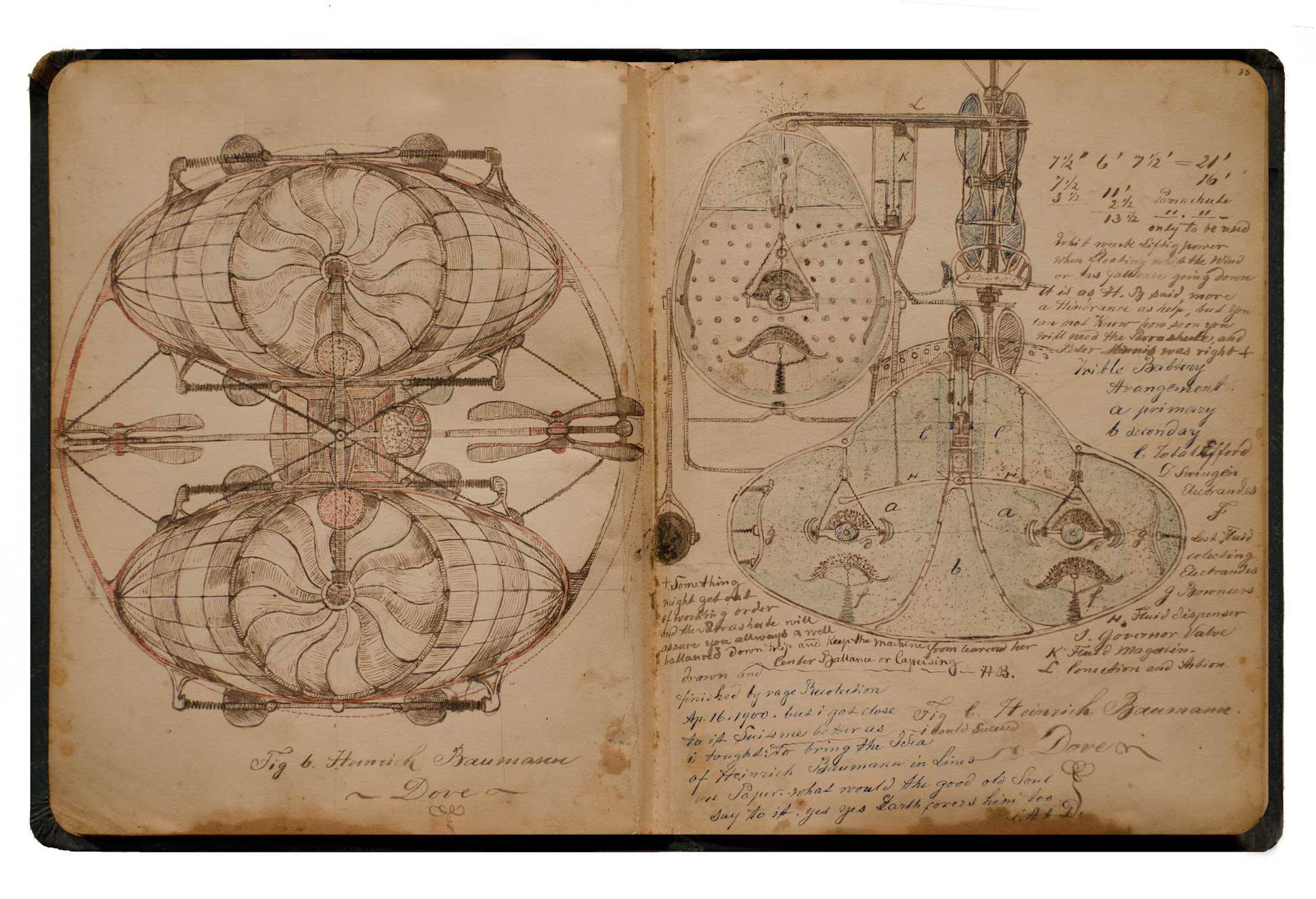

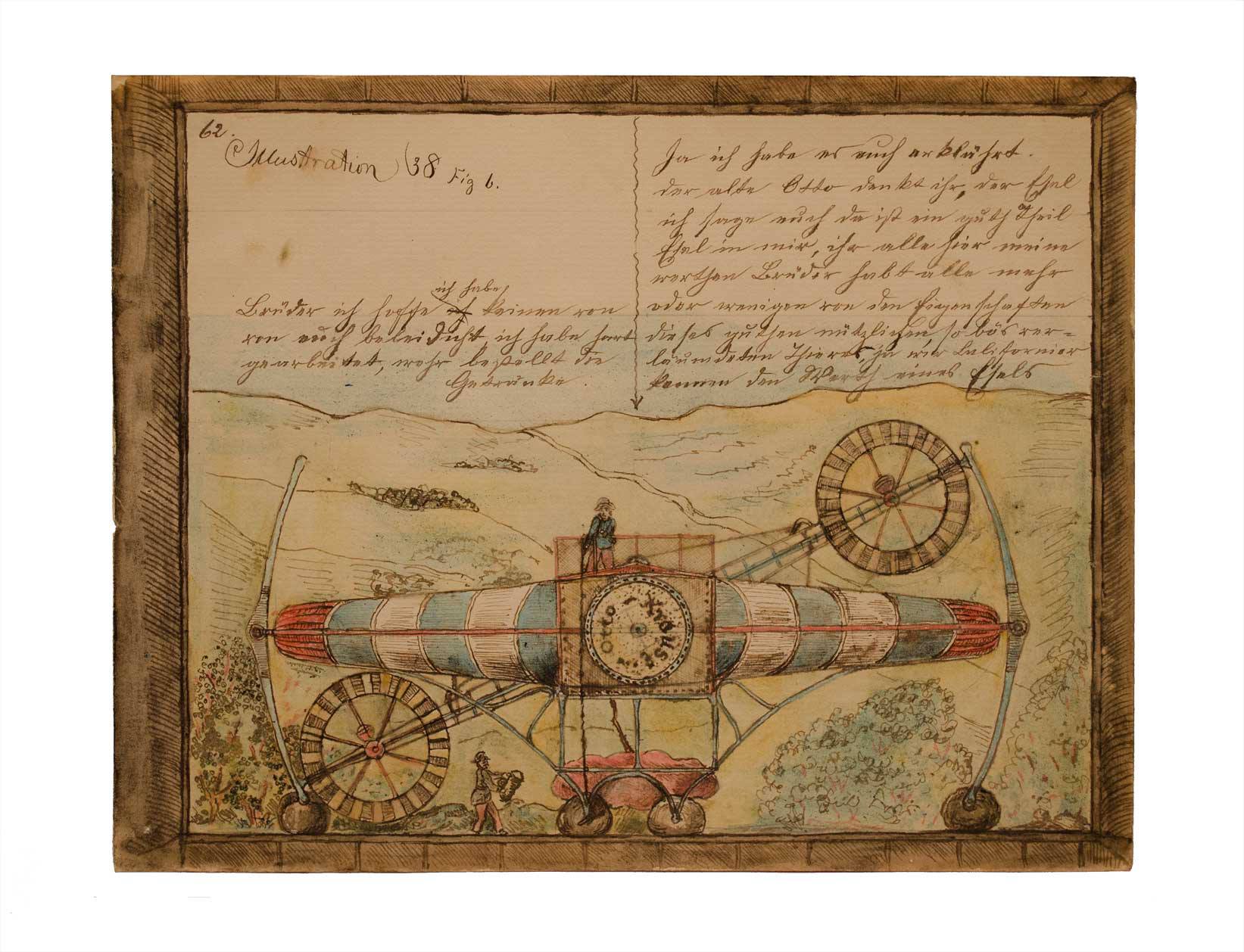

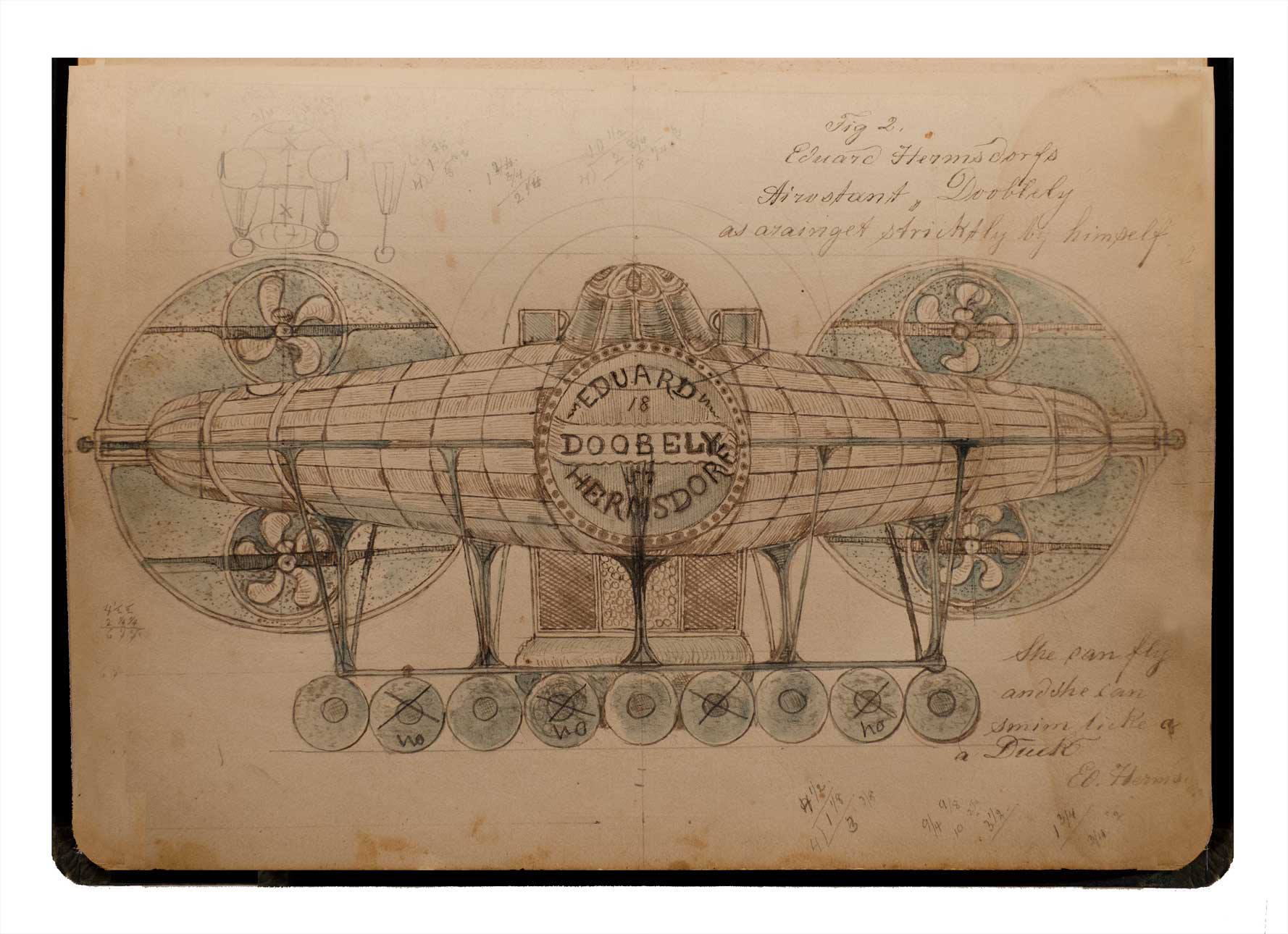

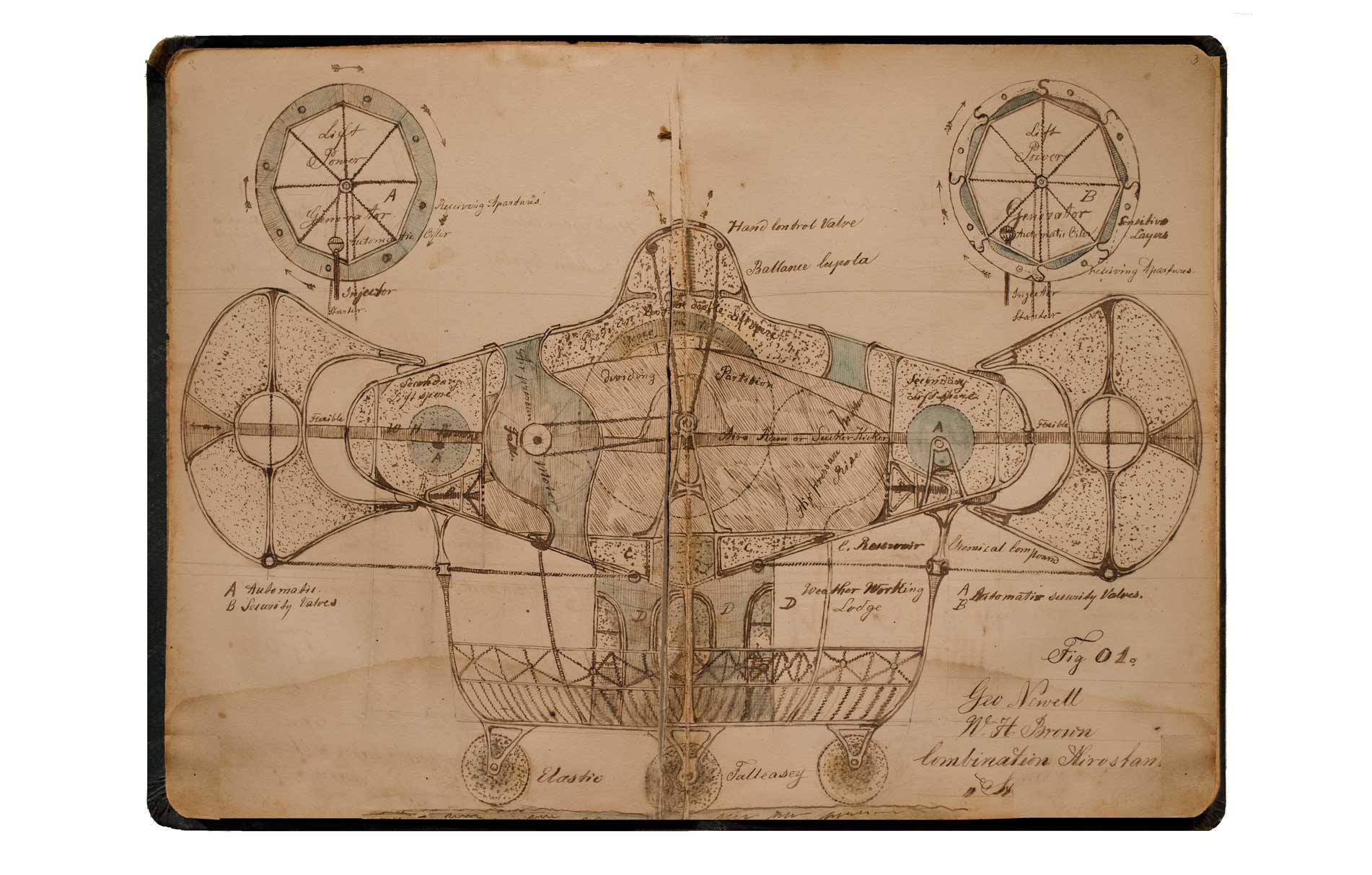

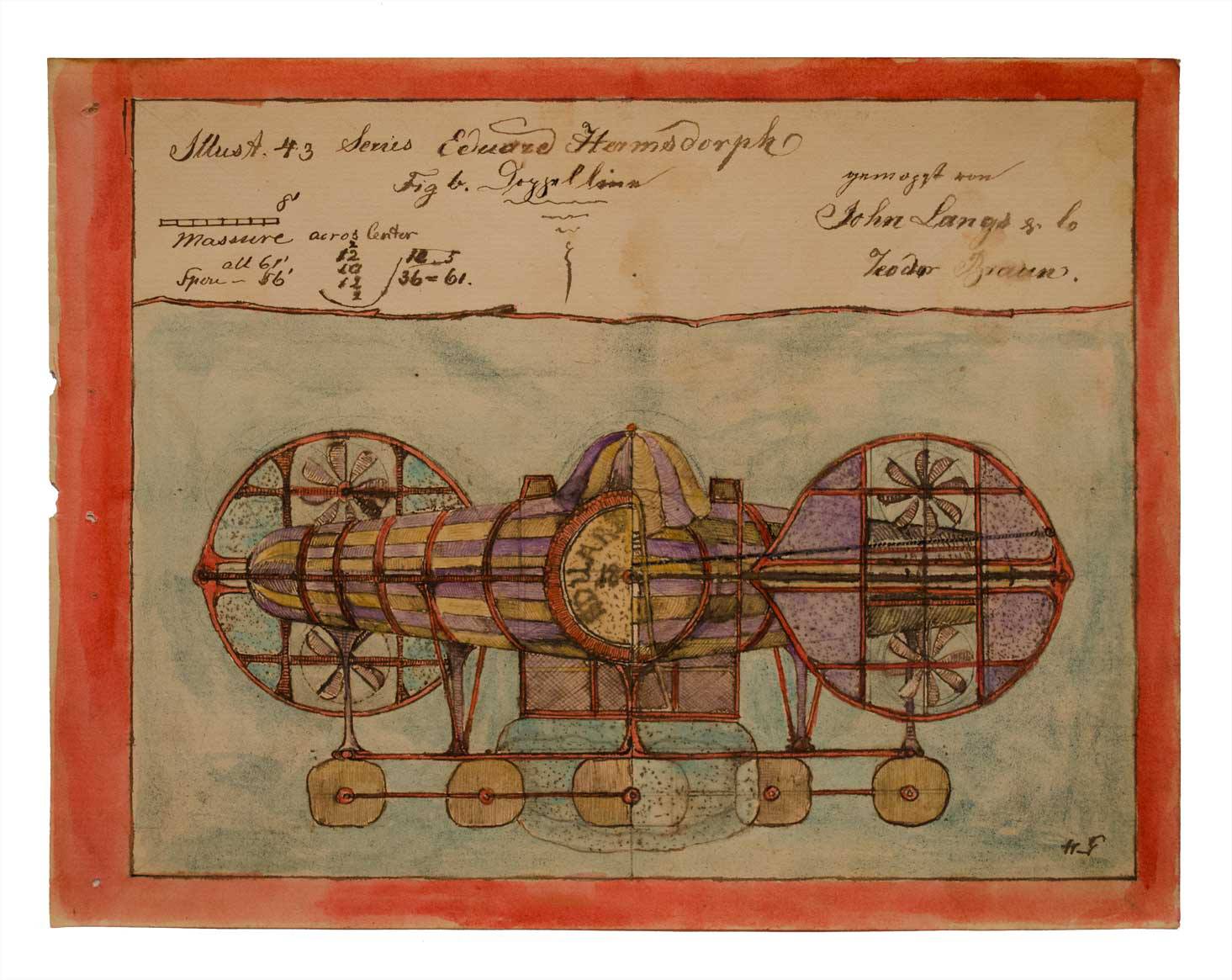

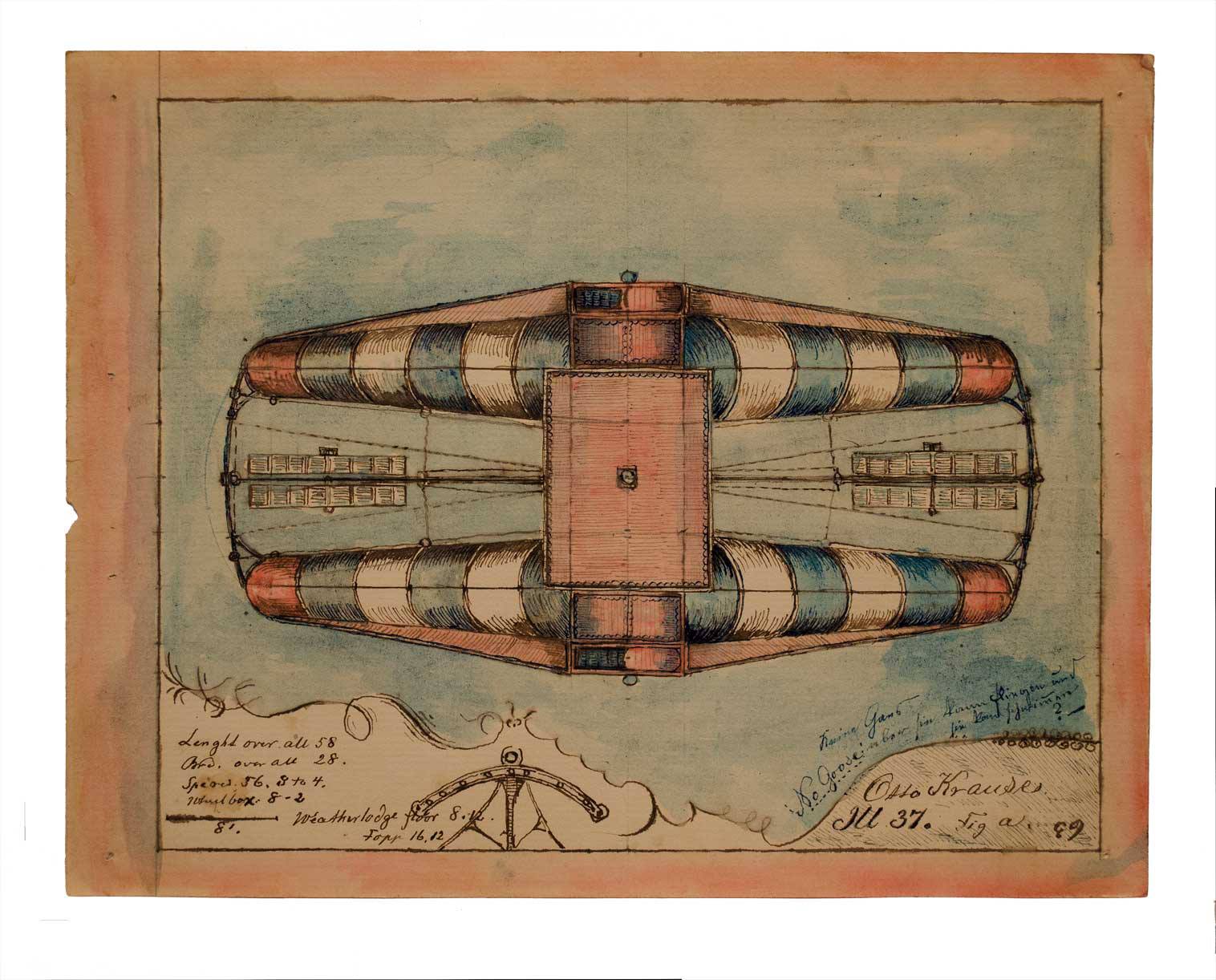

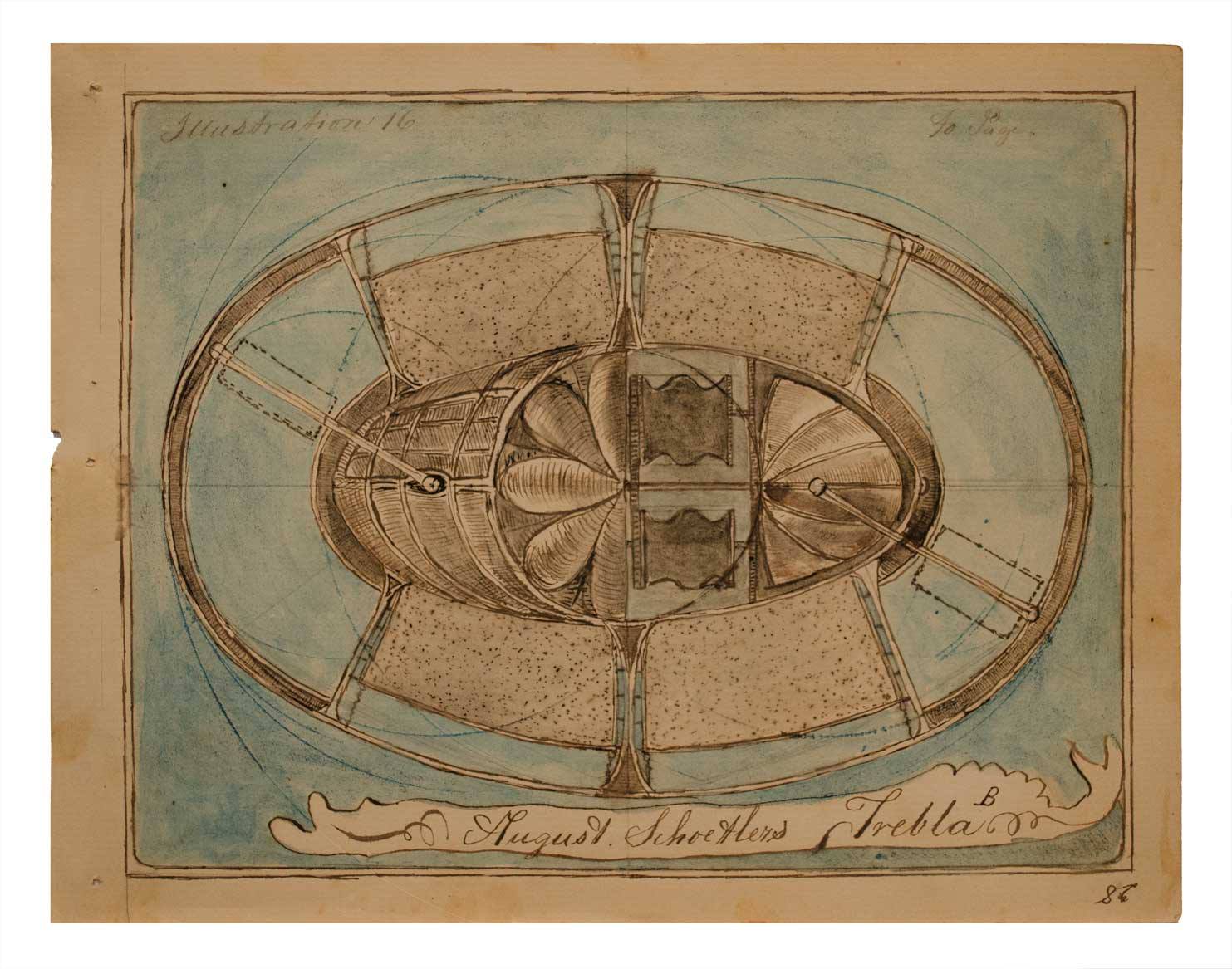

Charles A.A. Dellschau (1830 – 1923), untitled watercolor on paper c. 1898 – 1900 approx. 8 x 10 inches.

NYMZA Aeros – Charles Dellschau and The Secret Airships of the 1850’s

by Jimmy Ward & Pete Navarro, 1970's

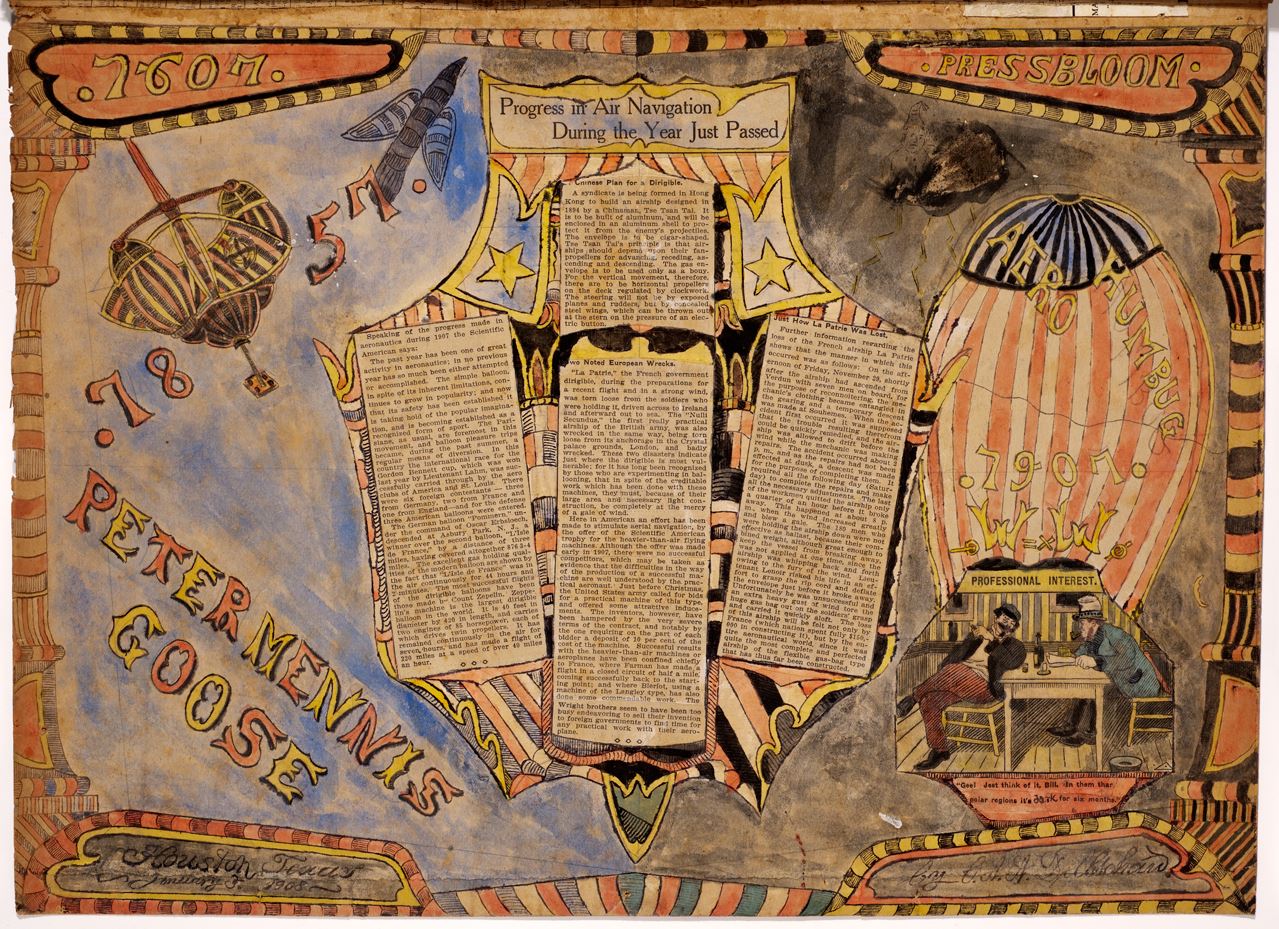

Have you heard of Schultz’ Hydrowhir Auto, also known as the “Cripel Wagon”? If not, perhaps you have heard or read somewhere about Peter Mennis’ “Aero Goosey”? How about Schoetler’s “Aero Dora”,

which was built in 1858 and was destroyed in a fire which consumed the town of Columbia, California that same year? Chances are you never heard or read about any of the above or the many other “Aeros’,

or aircraft that were designed and actually built and flown by members of the Sonora Aero Club around the middle of the last century in California.

Charles A.A. Dellschau (1830 – 1923), untitled watercolor on paper c. 1898 – 1900 approx. 8 x 10 inches.

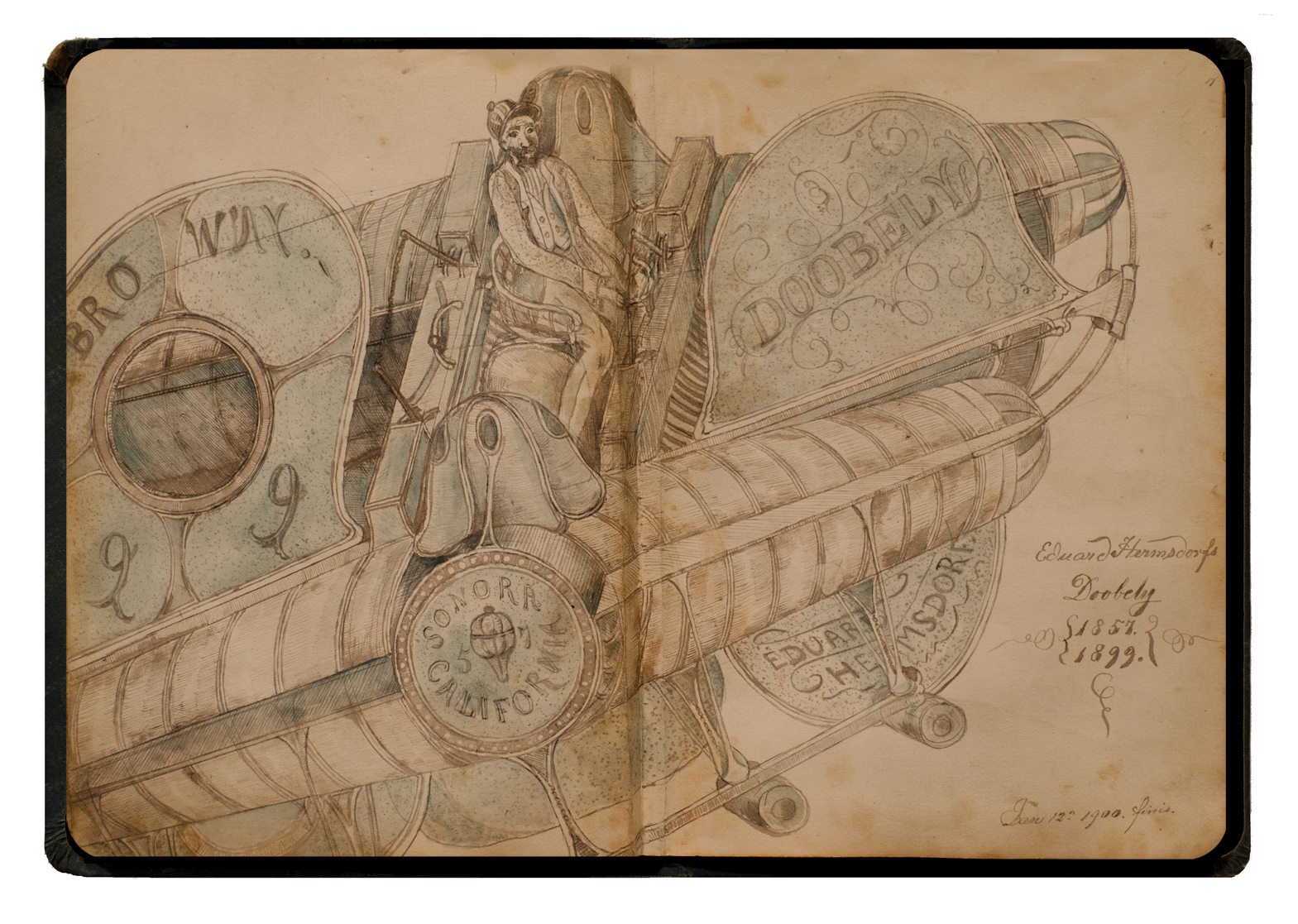

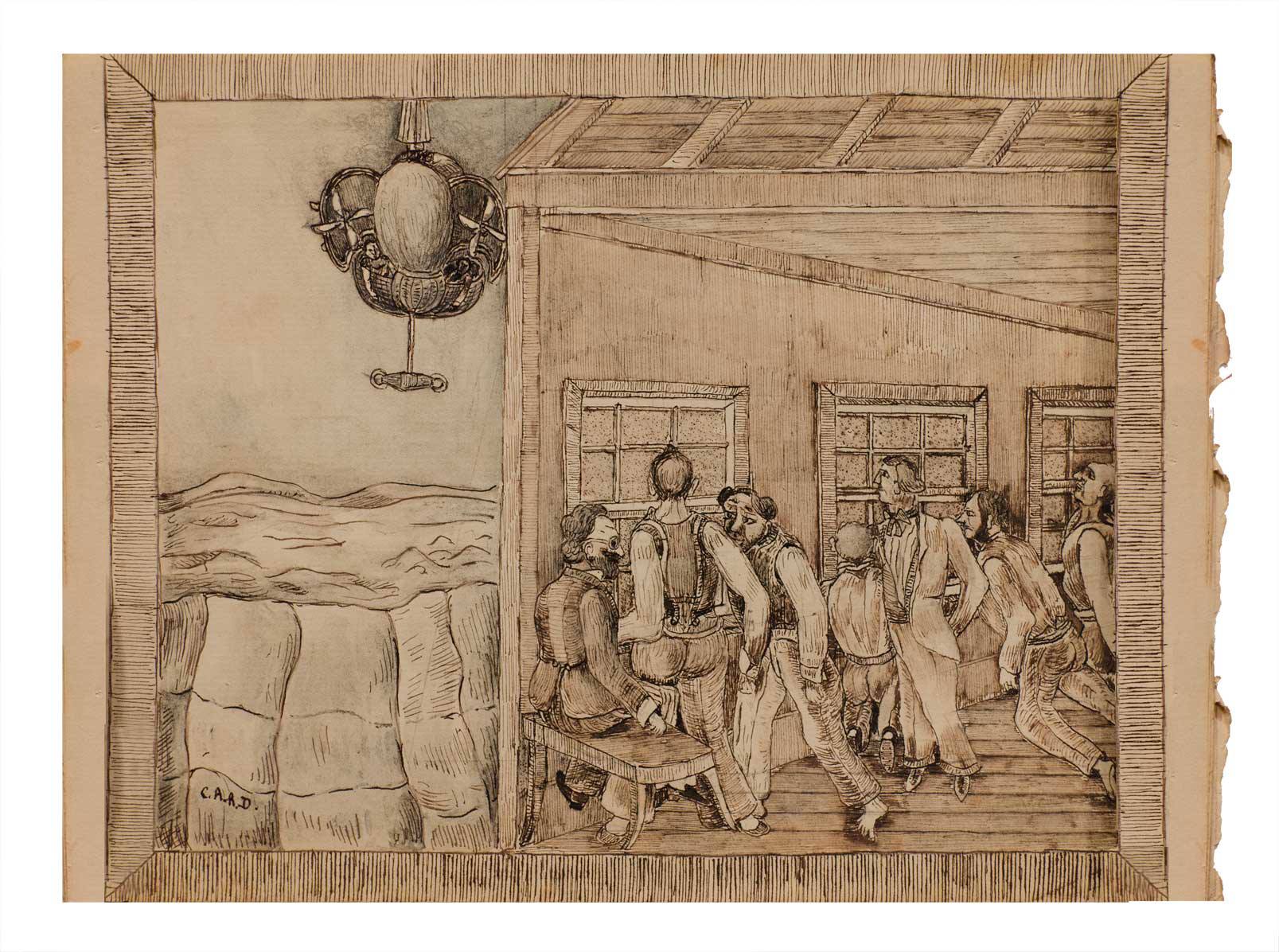

These aircraft were navigable airships, designed and built at a time when the only means of flight was the aerial balloon, which lacked maneuverability and was subject to the whims of the wind. According to C.A.A. Dellschau,

a member of the Sonora Aero Club who kept a secret record of all their activities and experiments which they carried out in the vicinity of Sonora and Columbia, California during the years 1850 to 1858, several of their airship

designs were built and flight-tested in the area which is now an airfield just outside of the town of Columbia. It is conceivable that these aircraft may have flown over the region as far as the giant redwoods area of California for

Dellschau states that one of their airships became accidentally entangled in the branches of a giant California redwood, resulting in the death of its pilot, who fell from the Aero and broke his neck. Dellschau referred to this aircraft

model as a “flying trap”, perhaps because it contained a device that was hung underneath the carriage of the airship and served as a “ballancier”. However, this device was dangerous, as it could easily get caught upon any tall

tree or obstacle close to the ground.

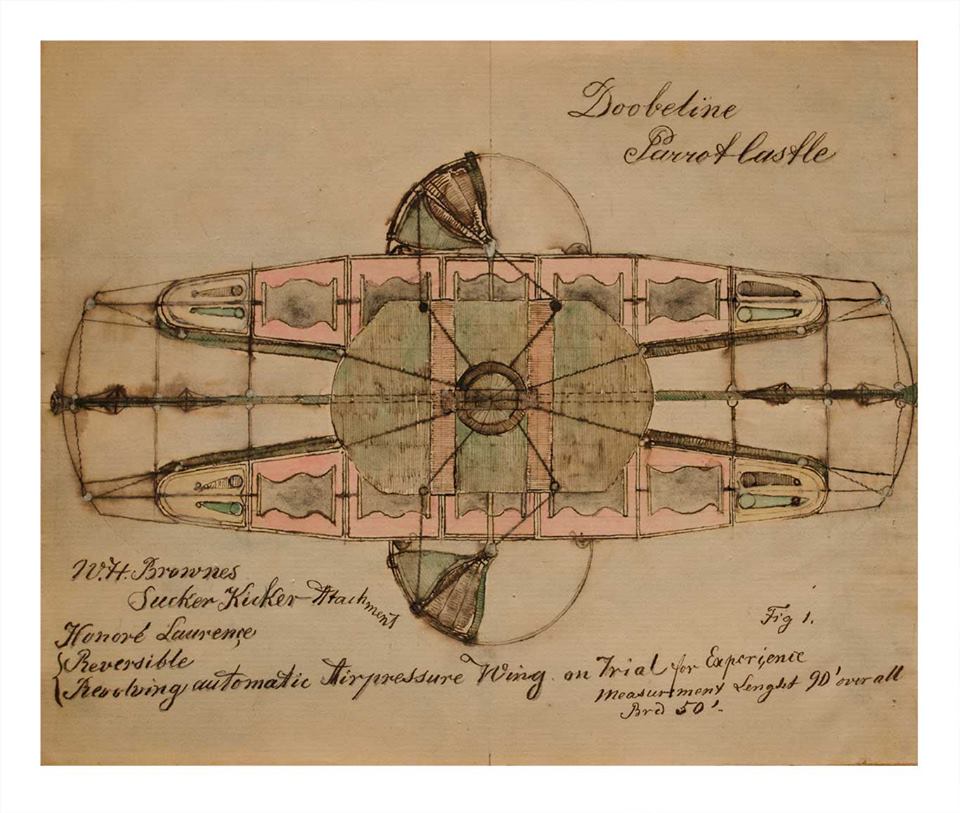

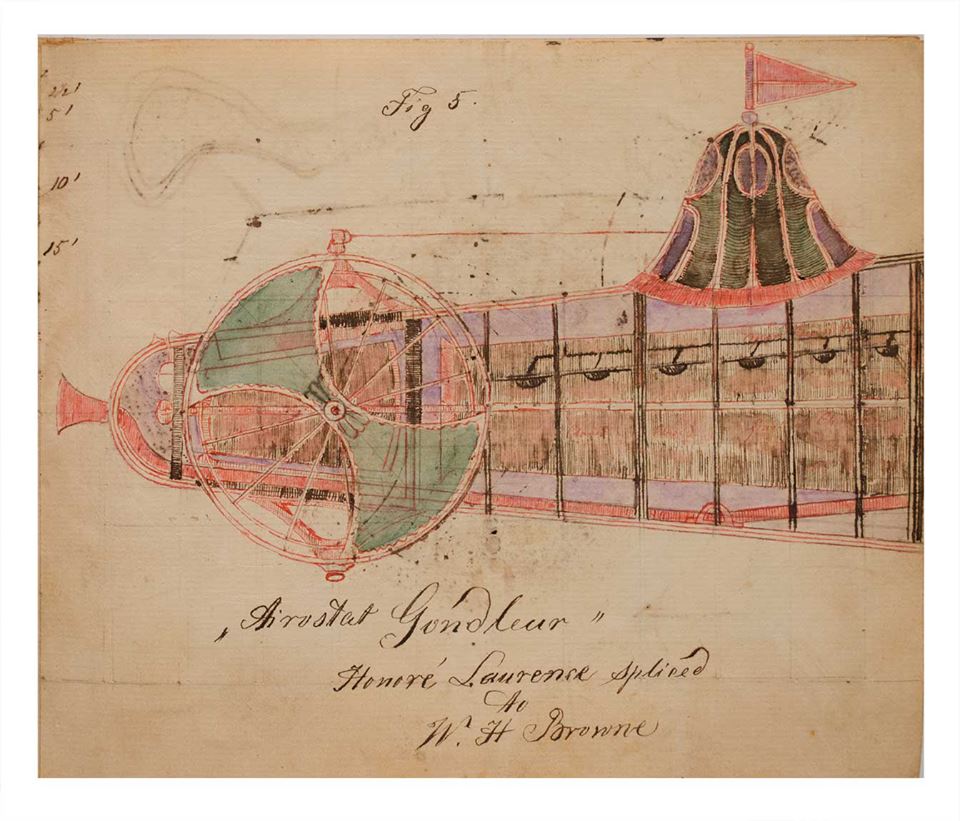

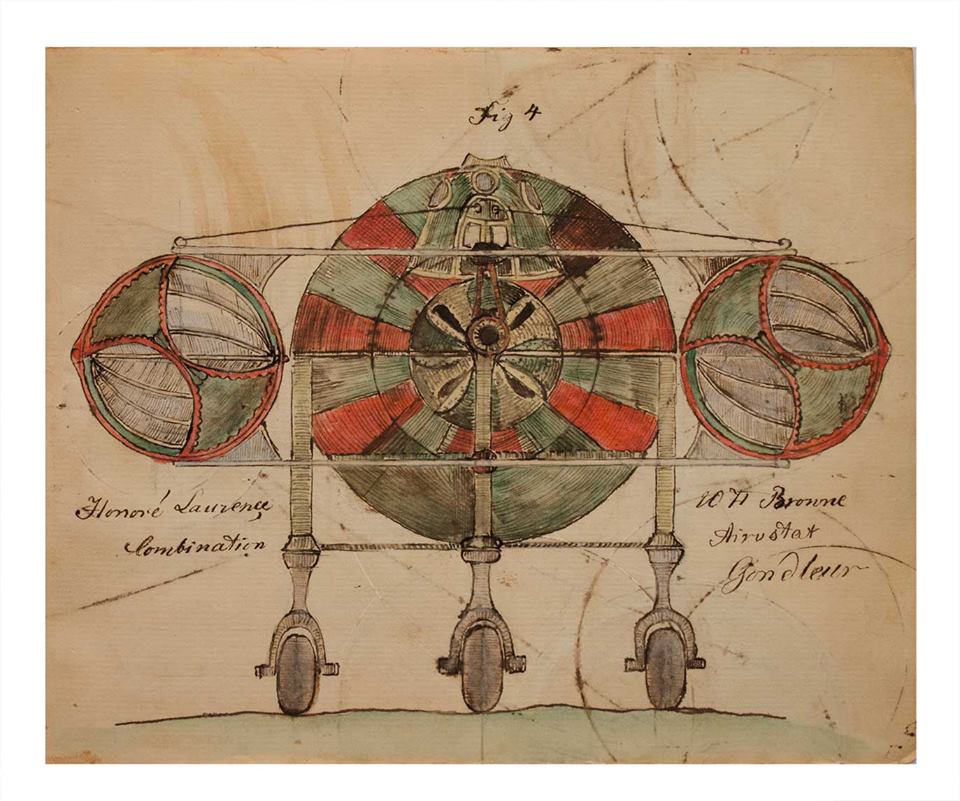

Charles A.A. Dellschau (1830 – 1923), untitled watercolor on paper c. 1898 – 1900 approx. 8 x 10 inches.

Charles A.A. Dellschau (1830 – 1923), untitled watercolor on paper c. 1898 – 1900 approx. 8 x 10 inches.

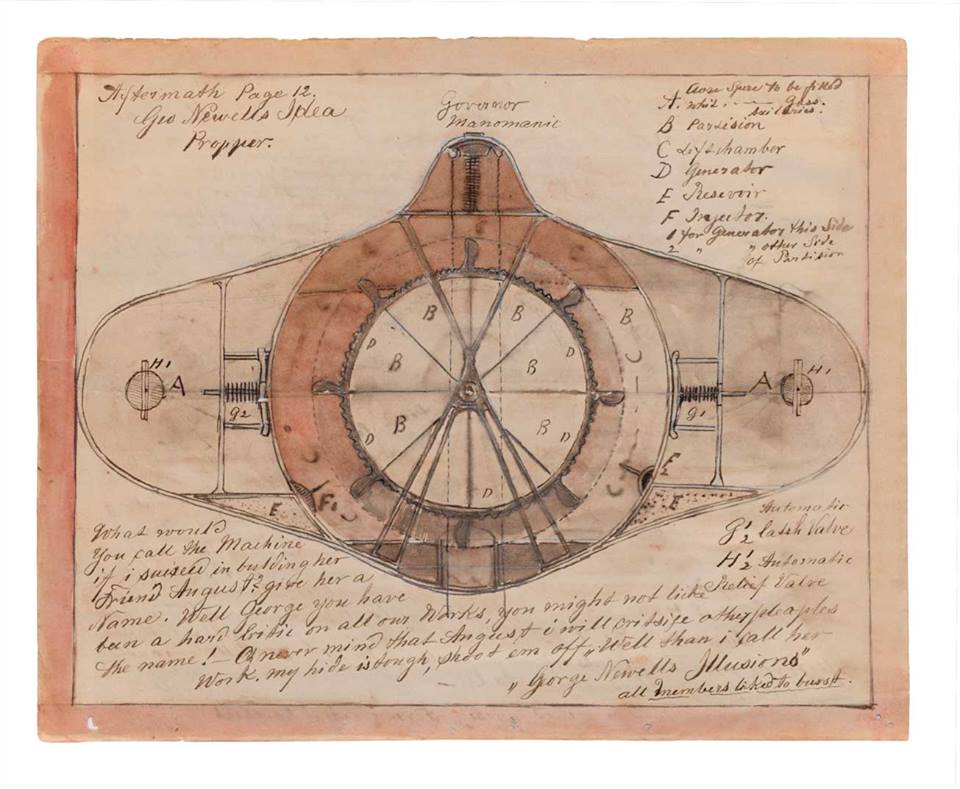

Charles A.A. Dellschau (1830 – 1923), untitled watercolor on paper c. 1898 – 1900 approx. 8 x 10 inches.

It is very possible that these aircraft were the progenitors of the Mystery Airships that were observed flying over Oakland and other points in California and in the Southwestern part of the country in the 1890’s.

.jpg)

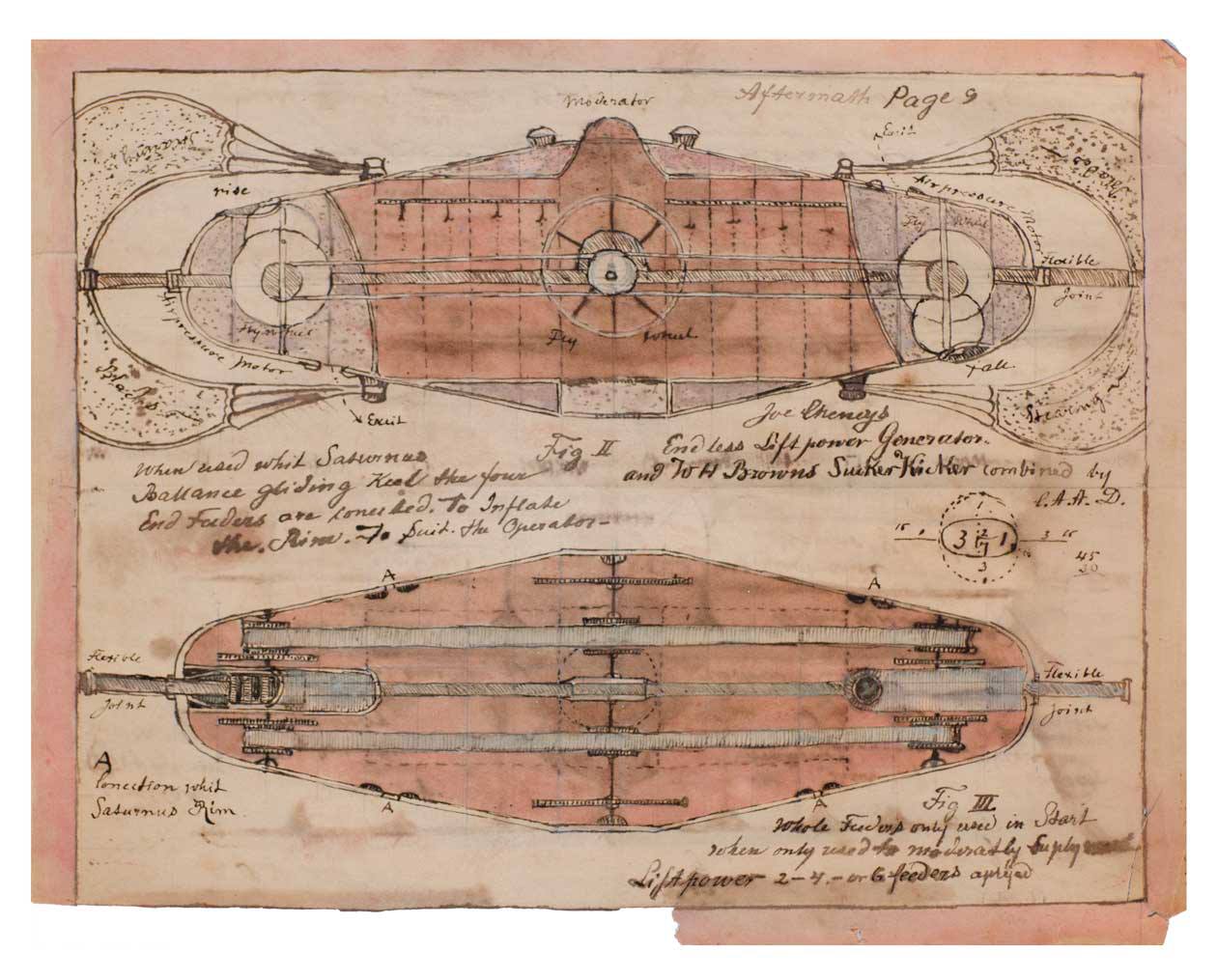

Charles A.A. Dellschau (1830 – 1923), untitled watercolor on paper c. 1898 – 1900 approx. 8 x 10 inches.

What leads me to believe that there was connection between these aeros and the Mystery Airships is the fact that, although Dellschau was an avid collector of news stories dealing with airships or anything aeronautical;

not ONE item concerning the Mystery Airship sightings is to be found among his collection. Could it be that he was reluctant to show any connection because of the fear of divulging matters of secret trust?

In one of his books the name WILSON is mentioned, and alludes to Wilson and his CREW. Anyone who has read of the stories that appeared in the newspapers of the 1890’s is probably well acquainted with this name,

for it is the name of the pilot of one of these Mystery Airships, and it is very possible that Dellschau was acquainted with him and his crew. But why all the secrecy?

Charles A.A. Dellschau (1830 – 1923), untitled watercolor on paper c. 1898 – 1900 approx. 8 x 10 inches.

Charles A.A. Dellschau (1830 – 1923), untitled watercolor on paper c. 1898 – 1900 approx. 8 x 10 inches.

It may be said here that members of the Sonora Aero Club were also adjoined to a secret organization or society known only by the initials N-Y-M-Z-A, which oversaw the workings of all its junior members. They were all subject to

strict obedience of the rules imposed by this Secret Society and the divulging of its secret operations was not permitted. It was for this very reason that Dellschau kept all this to himself and eventually, when he finally decided to write about

it he did it secretly, and this in code and in cryptograms and symbols, which only those with the patience and willingness to spend time in deciphering his writings would be able to read it and know what had been accomplished by them.

Vanguard note..

Strangely enough, I (Jerry) know a lady technical representative who is based out of Hollywood, Florida. In December of 1991, I was telling her about the Aeros and the mysterious substance known as N.B. or “float” gas. She was much

interested and told me that her late grandfather was a member of some super-secret group which had secret meetings and seemed to have contacts overseas.

She said that as a little girl, she had lived with her grandfather for one summer. He had a huge library with all sorts of strange books, some in a code type of language. She was not allowed entry into the library or certain rooms of the house.

When asking her father about what her grandfather was involved with, he told her that his father was a member of what he claimed was a very secret and very ancient group. This group was several hundred years ahead of mankind and

members were sworn to secrecy under threat of death.

Charles A.A. Dellschau (1830 – 1923), untitled watercolor on paper c. 1898 – 1900 approx. 8 x 10 inches.

Charles A.A. Dellschau (1830 – 1923), untitled watercolor on paper c. 1898 – 1900 approx. 8 x 10 inches.

The lady also told me that when her grandfather died, men showed up at his house with signed papers giving them the right to remove whatever they felt was necessary. The men took the majority of his library and all his private papers. They

also took what was in the rooms she was forbidden to enter as a child.

Her father was also forbidden to pursue the matter although he also spied on his father when he was young. The mysterious men also collected the majority of the grandfather’s inheritance which was bequeathed to the group. This might

possibly give us a clue since there must be records as to WHO received the inheritance, either a person or a group. That in turn would give us a further name to look into.

The grandfather was a strict vegetarian and had very precise and detailed habits which he believed had allowed him to live to his ripe 70’s, yet he looked like a man in his late 40’s. She also said he would walk in the grass early every morning

and said that the dew was very beneficial to life.

I have asked her for specific names and any other information she could gather relating to her grandfather, specifically a newspaper article she was sent about 2 years ago. She promised to find it and make me a copy. This could lead to

something if such a group exists in fact.

Charles A.A. Dellschau (1830 – 1923), untitled watercolor on paper c. 1898 – 1900 approx. 8 x 10 inches.

I asked her if the group might have been either Rosicrucian or of a magical nature and she said, no, that it was very scientific and dealt heavily with music. Her grandfather owned and operated a school of music in which he got heavily involved

after joining the group. Prior to that, music was not his means of income.

Also, as to the name NYMZA, Jimmy and Pete say that these German immigrants might have used either German or a combination of German and English. Since they were based in the East, it would follow that NY would equal New York,

M could equal Mechanical, Z could very well equal the German word Zephyr (meaning wind from the west), and A could mean Association.

So we have the term, New York Mechanical Zephyr Association, or NYMZA, indicating mechanical flying devices from the west, as would be seen through a European (eastern) viewpoint. Just an attempt to derive a logical name, might be incorrect.

Charles A.A. Dellschau (1830 – 1923), untitled watercolor on paper c. 1898 – 1900 approx. 8 x 10 inches.

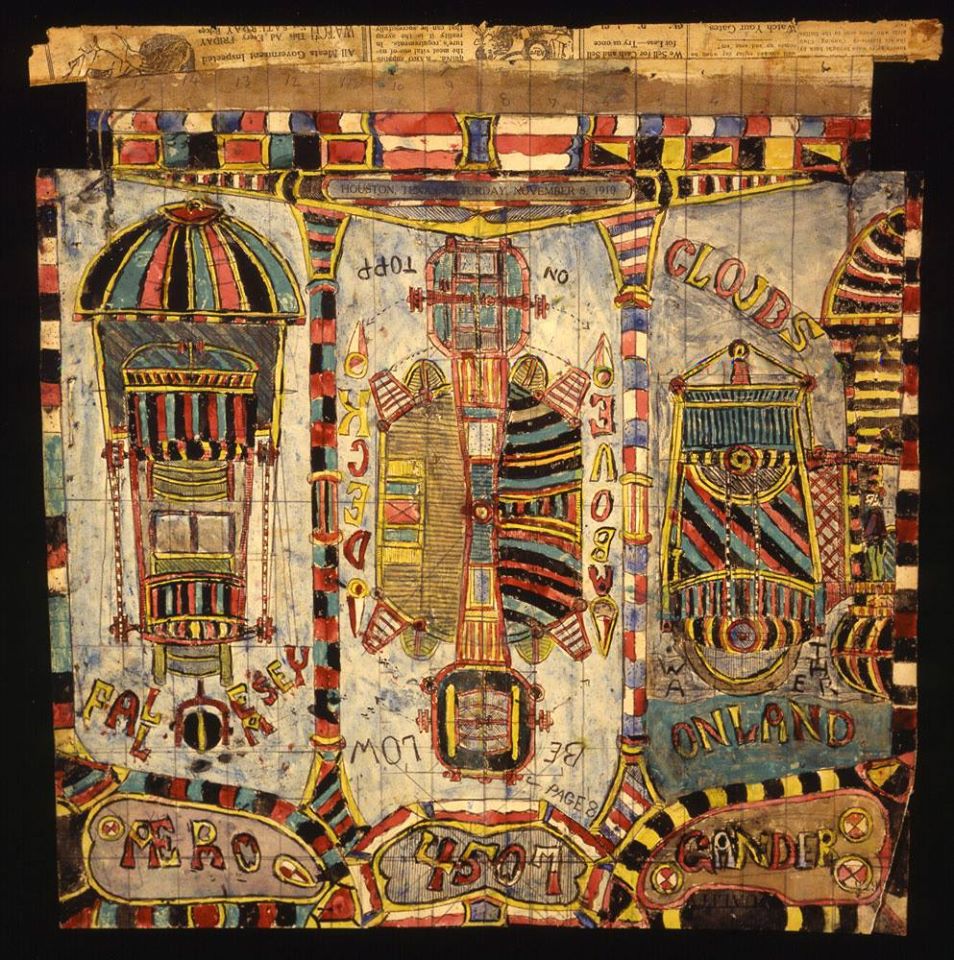

The tragic case of Jacob Mischer and his Aero will serve to point to the severity with which the rules of this secret society known as NYMZA were enforced.

Jacob Mischer was the designer and builder of a rather large, or medium-sized aircraft which was called the “Aero Flyerless Gander”. This airship was flown on a hundred mile trip and was successfully landed on land and on water, for it had

wheels as well as pontoons.

Jacob Mischer, however, met a most unfortunate end, for he became greedy and desired to make a profit from his invention, intending to use it for hauling material and equipment for the miners in the area. This was looked upon by the

headmasters of the secret society as being strictly against the rules and, one way or another, Jacob Mischer ended up dead when his ship was destroyed in a blinding aerial explosion. Dellschau alludes to this incident as something that was

deliberate and NOT accidental.

Charles A.A. Dellschau (1830 – 1923), untitled watercolor on paper c. 1898 – 1900 approx. 8 x 10 inches.

Charles A.A. Dellschau (1830 – 1923), untitled watercolor on paper c. 1898 – 1900 approx. 8 x 10 inches.

Charles A.A. Dellschau (1830 – 1923), untitled watercolor on paper c. 1898 – 1900 approx. 8 x 10 inches.

Charles A.A. Dellschau (1830 – 1923), untitled watercolor on paper c. 1898 – 1900 approx. 8 x 10 inches.

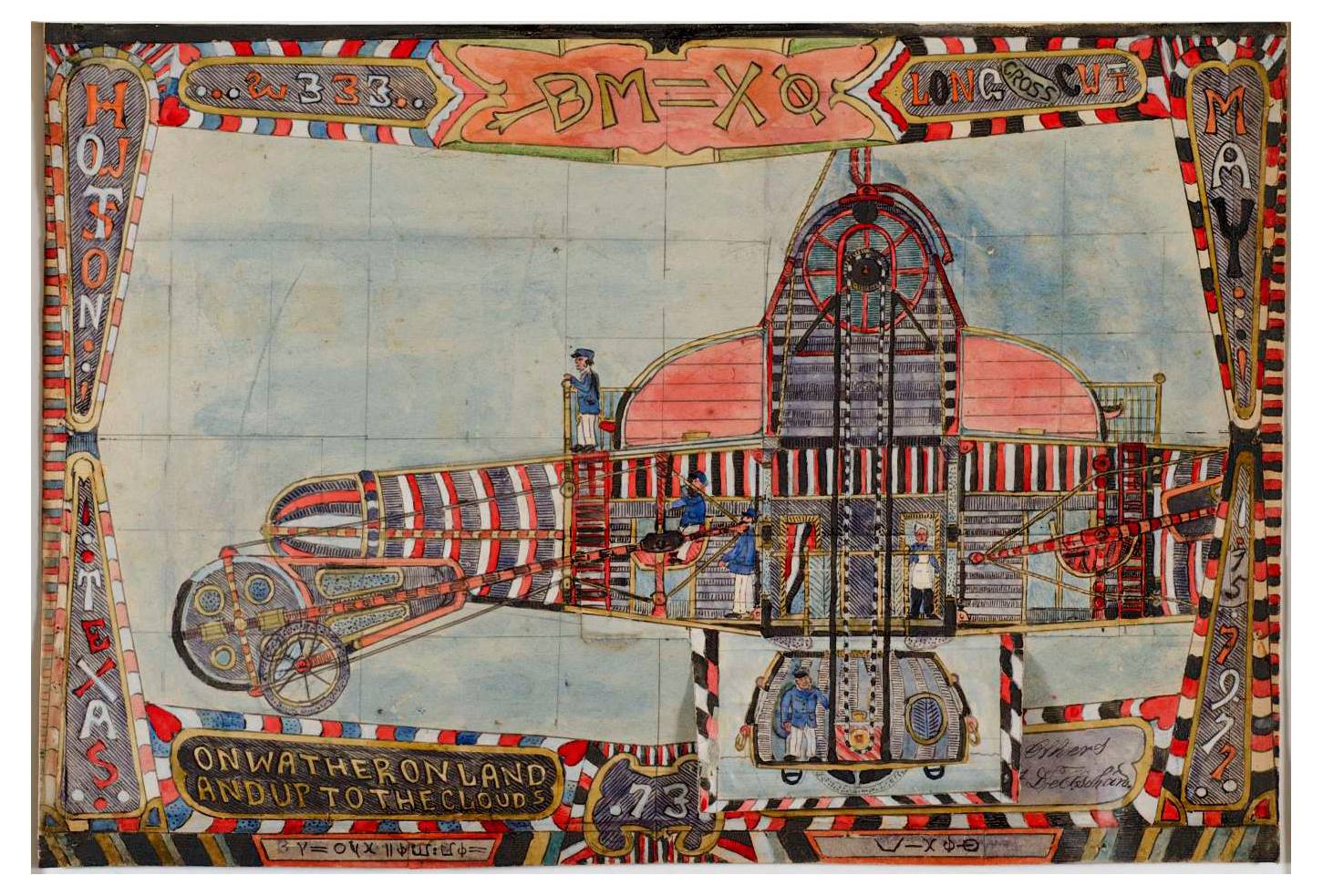

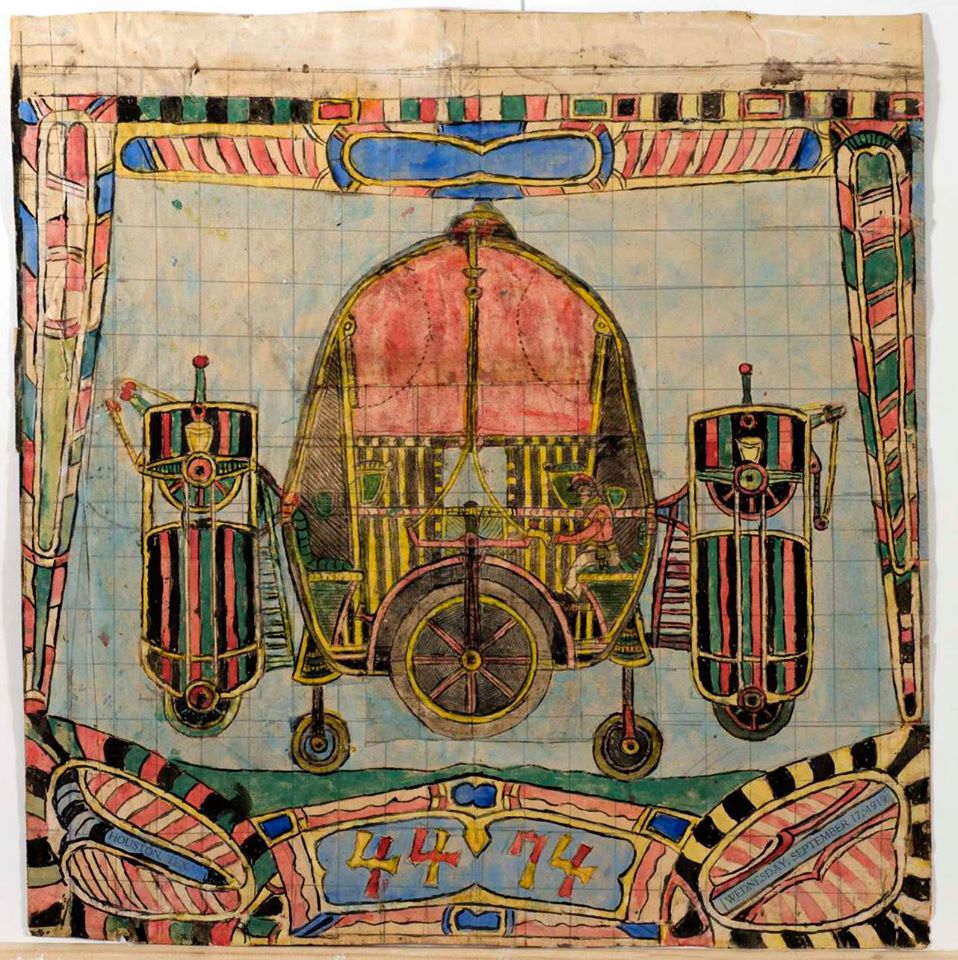

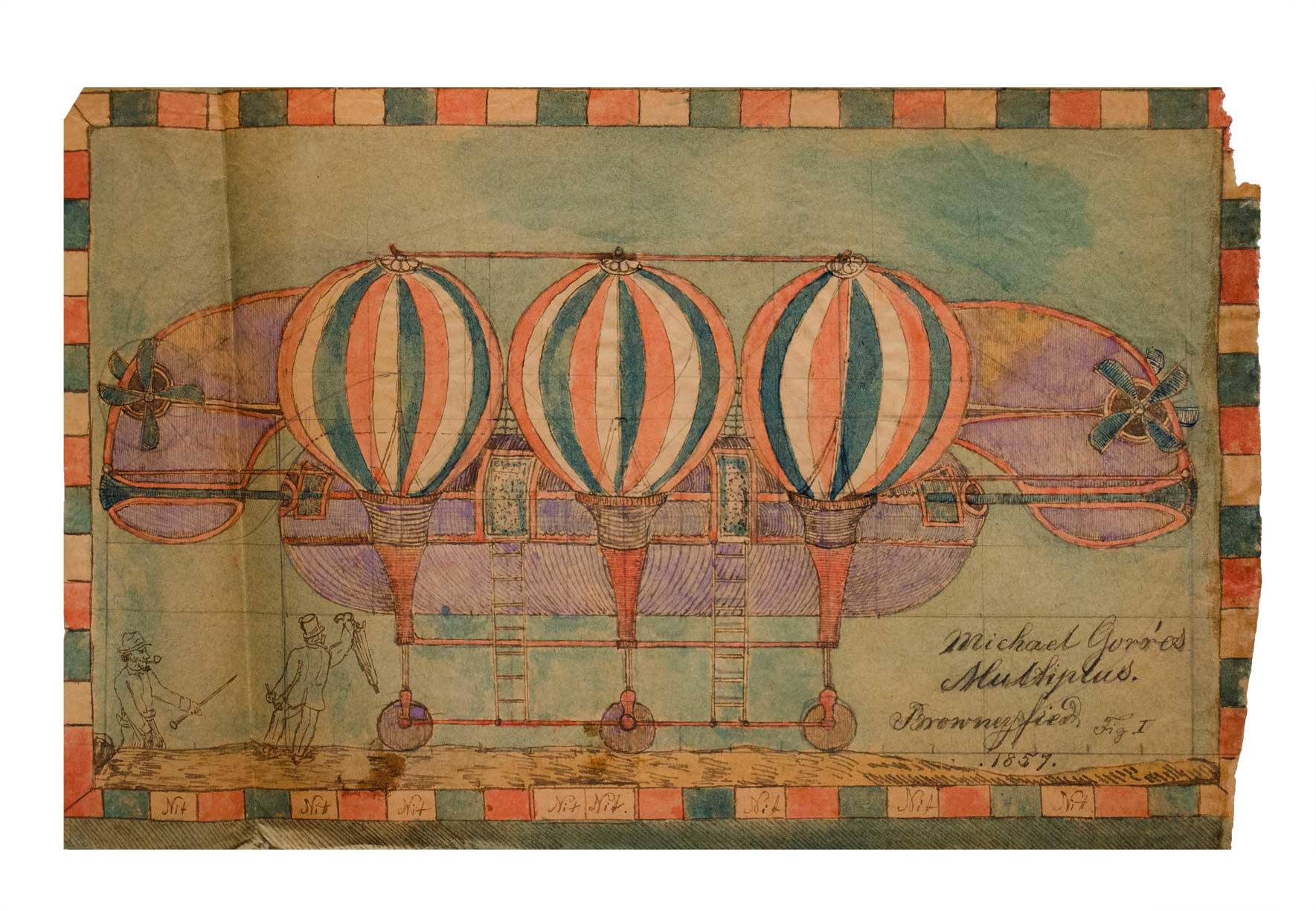

The most successful of their aircraft, and probably the first to be flown was Peter Mennis’ “Aero Goosey”, which was built in 1857 and set the precedent for all subsequent Aero designs and, although modifications were gradually added to

new Aero designs, the Aero Goosey continued to be flown as originally designed with only minor changes and was the aircraft favored mostly by Peter Mennis for short flights.

Peter Mennis ranged far and wide on several occasions, but he was able to land and use his Aero as a place to spend the night, for it was equipped with a canvas cover which served as a tent.

The original “Aero Goosey” was a small craft with a basket-type affair in which the pilot and passengers sat at the bow and stern ends of the airship. It carried a liquid fuel container in the center of the craft and a gas converter under the

seats. Attached to the center pole was the air-pressure motor which was used to propel the airship, and two gas bags were on the sides. It was a very simply designed airship, and, despite all modifications and improvements that were made

upon this original model and its “motor” design, the mode of operation and function of its internal workings remained basically the same in all subsequent models with the exception of size and appearance and the addition of useful conveniences

such as galleys, toilets, beds, tables, and other gimcracks of one kind or another.

Louis Caro, another member of the Sonora Aero Club expressed it very well when he said that he and his colleagues agreed on one thing; and that was the fact that they all longed for an airship design which would have all the features of the

Aero Goosey, but be larger and yet be safe. Several very large models were designed toward this end and proposed but were never built. There were, however, several medium-sized models which were actually built, and flown.

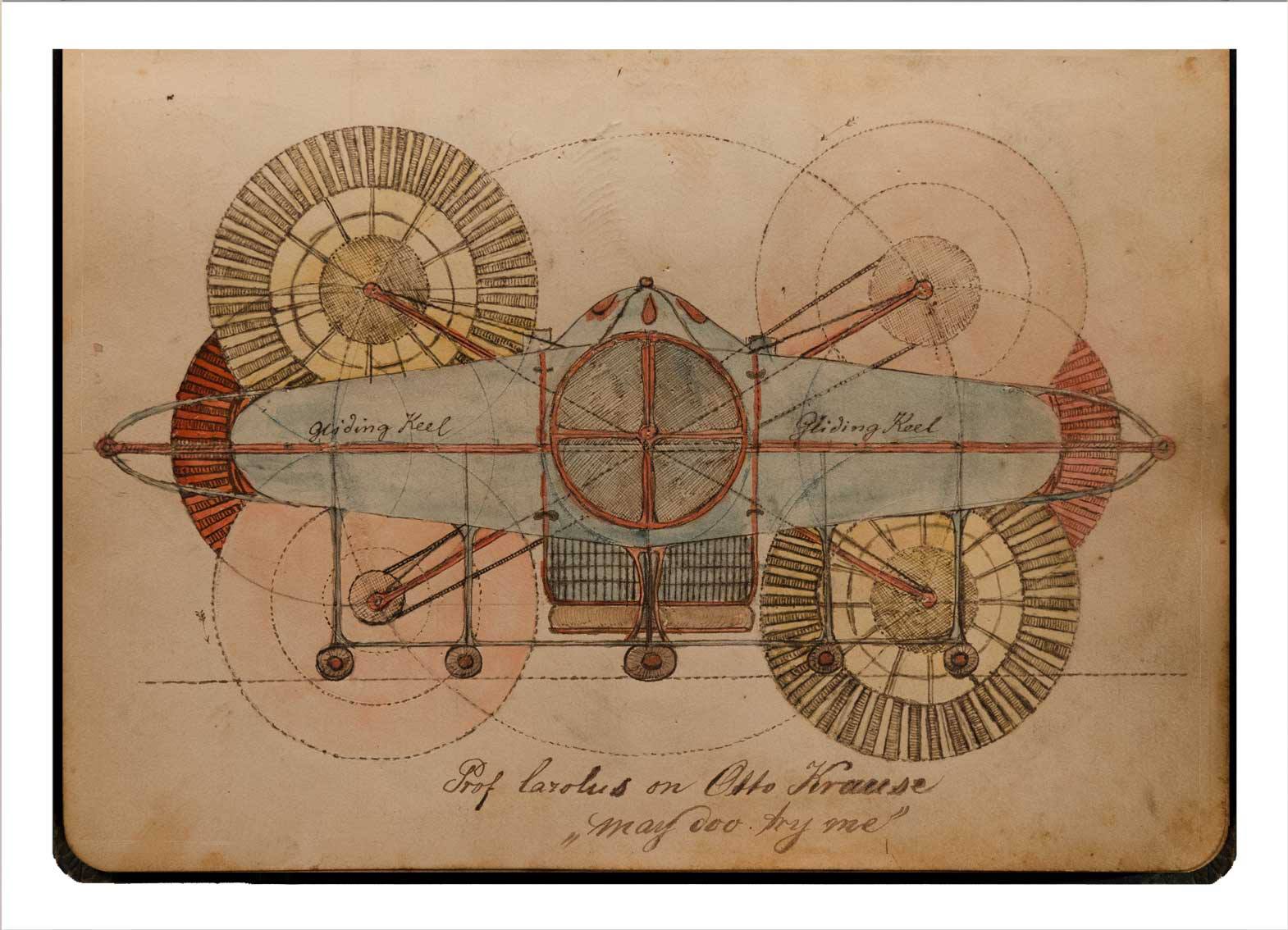

One of these was the “Aero Dora”, which was another of the most favorable designs. This Aero was first envisioned by Ernest Kraus and was later elaborated upon by several other members of the club who were very pleased with its

appearance and function and used it as a basis upon which to apply their own ideas.

The Aero Dora was equipped with a "sucker-kicker", which was a

device for compressing air and operated very much like a JET for

propulsion. Yes, several of these Aeros had devices that were years

ahead of their times, and included up to date contrivances such as

retractable landing gear, shock absorbers, gas converters, spot-

lights, and many other novel ideas for their time, for one must take

into consideration that these were entirely new concepts, or

designs, with absolutely no precendent to go by, and it is for this

reason that some of the aircraft look so fantastically monstrous and

absolutely unfeasable as aeronautical machines. In other words,

none of them look like they could even BEGIN to get off the ground,

much less fly!

This was no problem for them though, for they possessed a formula

for producing a SPECIAL GAS, called "NB" gas, which was capable of

lifting the most ponderous construction with a minimum of gas. The

gas was produced on board the aircraft and carried in one or several

gas bags on top or on the sides of the airship. Marthin Karo, one

of the members of the Club and inventor of a "hood" for carrying

excess gas referred to this lifting agent as "FLOAT", which is a

good description of its function.

George Newell was the inventor of a "gas motor" called "VOLTA" which

produced the "Lift Power" used on most of the airships. This was a

modified version of earlier gas motor designs or "converters" which

were used in earlier Aero models.

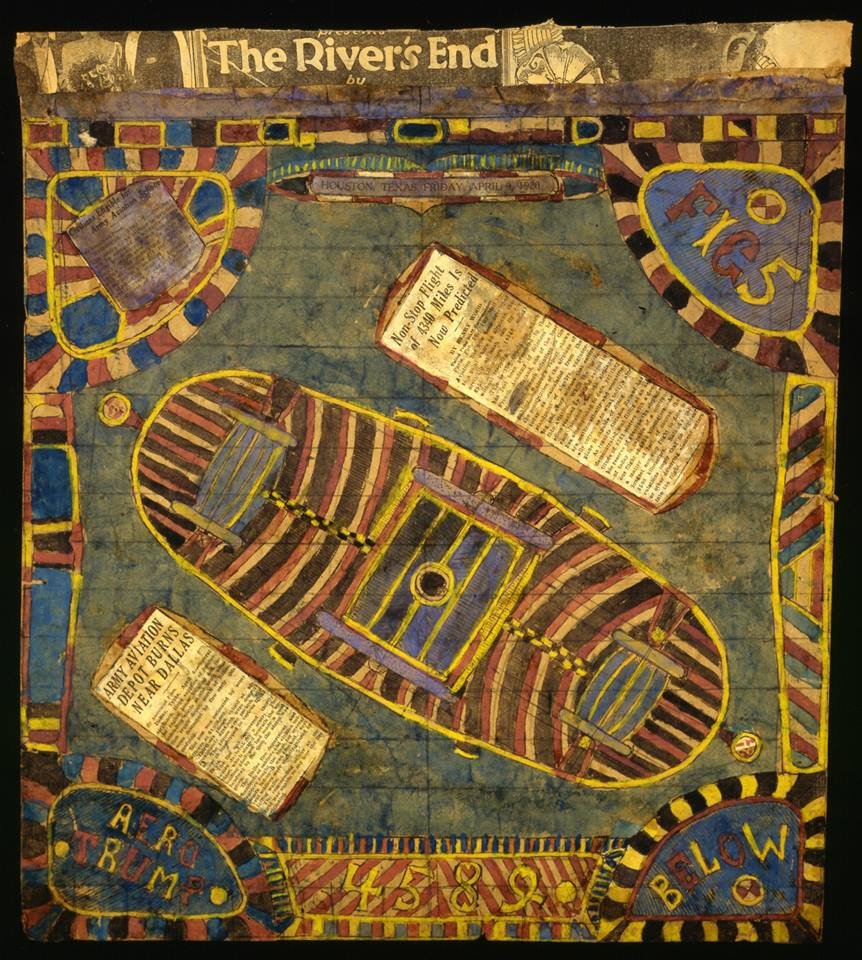

As for the Cripel Wagon...this was actually a wheeled land vehicle

designed in 1837 by Friderich Schultz but was adapted in 1857 for

use as an airship by August Schoetler with the addition of gas bags

and "air squeezers" which made the vehicle airborne, converting it

into an airship with hydrowheels (wheels with water inside instead

of air). "Air squeezers" were similar to "sucker kickers" and

consisted of a tube through which air was compressed and ejected

(similar to a jet engine).

The "Aero Buster" was an airship that was built but never flown. It

was designed and built by Max Miser and was equipped with a

parachute-like device. Before it was completed Max Miser remarked

that if his Aero ever got off the ground he would not want anybody

going up in it but him. "I am enough to break my neck", he said.

The Aero was completed except for the installation of the power

chamber and the fuel which only Peter Mennis could provide, since he

was the only one who knew the secret formula for producing it.

However, for some unkown reason, Peter Mennis refused to provide the

fuel or help Miser with the construction of the gas producing

chamber and consequently this aircraft was never able to get off the

ground. Many years later (in 1912) Dellschau would reminisce about

this incident and would remark on whether gasoline would have

"filled the bill" and would have made it possible for this airship

to fly. Of course, gasoline had not been discovered yet.

Of the more than one hundred airship designs in Dellschau's books

probably not more than eight or ten were actually built and flown.

And they were a howling success!

Why they didn't announce it to the world and reap their share of

profits and fame from their efforts is strange indeed. Could it be

that they were only conducting tests for others to follow? It is

only too clear that NYMZA was a very strict organization and that

any member who disregarded the rules of this secret society usually

PAID WITH HIS LIFE.

Dellschau faced the same threat to his life and it is believed that

he may have died a violent death, although this is strictly

conjecture. The fact is that Dellschau died in the year 1923 at the

age of 93 and was buried in Washington Cemetery in Houston, Texas.

He left behind a dozen large volumes in which he told many things

about their activities in California, but he never would say WHAT

NYMZA WAS, nor what the initials stood for, except to say that it

was work being done FOR THIS ORGANIZATION. Thus NYMZA remains a

mystery to all except to those who may read this and KNOW its

significance, for there may still be members of this society who

will continue to keep their vows of secrecy and may still be working

on yet other clandestine projects. You may very well ask; What

experiments could they (the present members of NYMZA) be engaged in

today? The spaceships of the 1990's? Who Knows?

P. G. Navarro

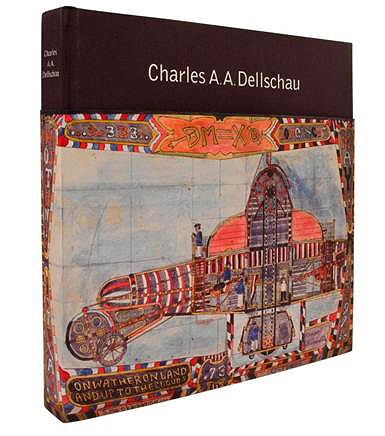

Books on Charles A.A. Dellschau:

A forthcoming book on Charles Dellschau entitled

CHARLES DELLSCHAU: A Higher Vision Is A Basic Demand Of Poetry

with a previously unpublished essay by Thomas McEvilley from 2013

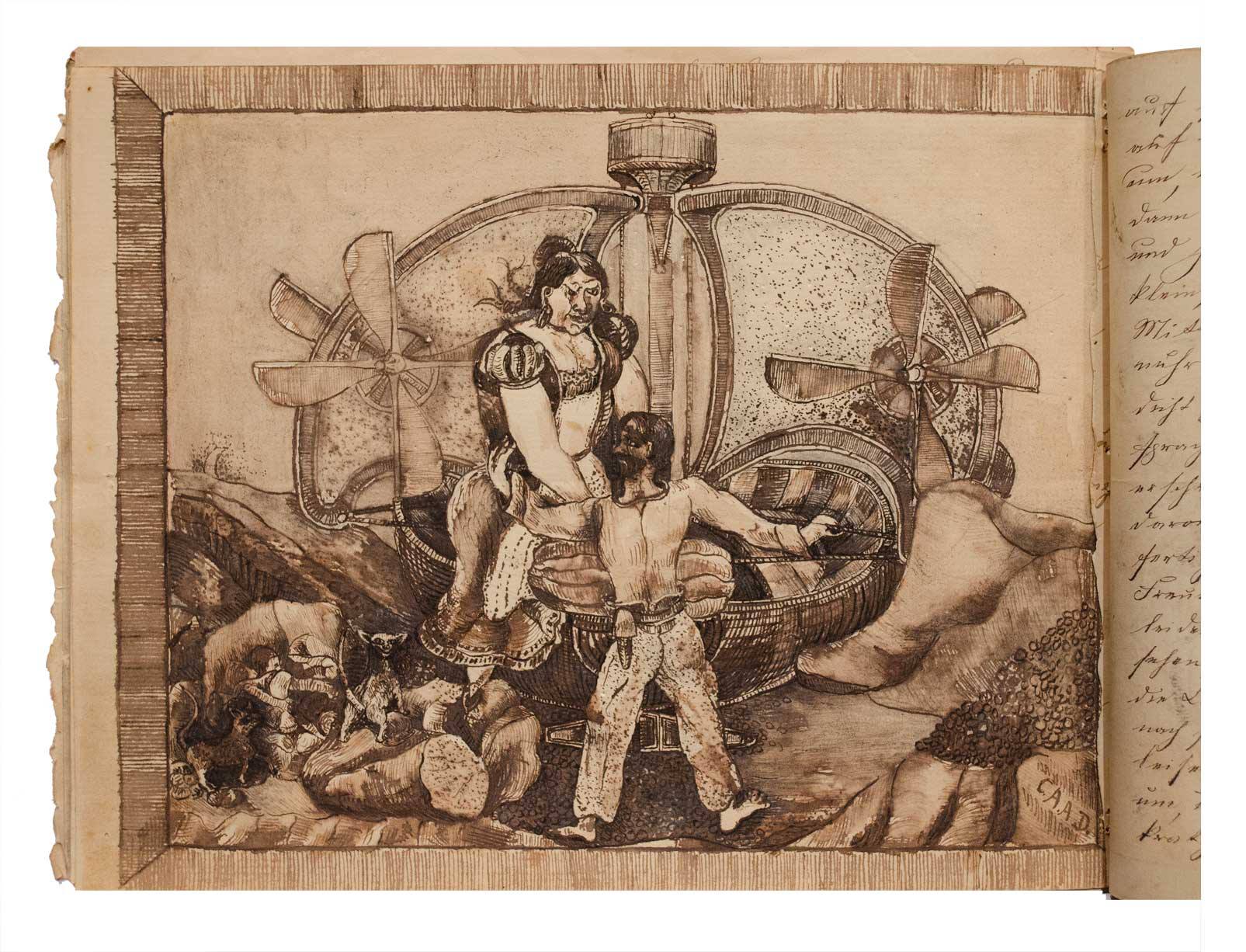

Charles A. A. Dellschau was born on June 4, 1830, in Brandenburg, Prussia, and immigrated to the United States in 1853, first settling in Texas. The historical record falls silent until 1860, when he is again shown living in Texas, where he marries

Antonia Hilt the following year. The so-called “lost years” of the secretive Dellschau’s life became a matter of controversy when his voluminous, illustrated notebooks surfaced nearly a half-century after his death in 1923 at age 93. Dellschau literally

spent the last 20 years of his life closeted away in an attic apartment, creating a fantastical body of art that continues to fascinate. Indeed, today Dellschau is recognized as one of America’s leading visionary artists, ranked alongside such world

luminaries as Henry Darger and Adolf Wölfli. A single page of one of his notebooks now fetches thousands of dollars – and there are thousands of such pages, frenetic productivity being a

This first monograph on Dellschau includes an essay by esteemed art writer Thomas McEvilley, a biographical overview by Tracy Baker-White, introduction by Stephen Romano and texts by Roger Cardinal of the University of Kent, James Brett

of the Museum of Everything in London, Tom Crouch of the Smithsonian Institution’s Museum of Air and Space, president of the ABCD Art Brut collection in Paris Barbara Safarova and writer and New York gallerist Randall Morris.

The second volume in the investigation of strange esoteric circumstances surrounding seven curious and questionable deaths in 1915 San Bernardino Valley. This book explores the unexpected fingerprints of a group of aviators who allegedly built

secret airships in California before the Civil War and may have been responsible for the widely reported but mostly forgotten Great Airship Mystery of 1897. Along with bizarre circumstances linking two of the victims to the airship milieu, the

possible identity of one of the victims also appears to bring the legendary outlaws Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid into the mystery.

Gallery of works by Charles A.A. Dellschau (1830 – 1923)

All images courtesy Stephen Romano Gallery, Brooklyn.

Charles A.A. Dellschau (1830 – 1923), untitled watercolor on paper c. 1898 – 1900 approx. 8 x 10 inches.

Charles A.A. Dellschau (1830 – 1923), untitled watercolor on paper c. 1898 – 1900 approx. 8 x 10 inches.

Charles A.A. Dellschau (1830 – 1923), untitled watercolor on paper c. 1898 – 1900 approx. 8 x 10 inches.

Charles A.A. Dellschau (1830 – 1923), untitled watercolor on paper c. 1898 – 1900 approx. 8 x 10 inches.

Charles A.A. Dellschau (1830 – 1923), untitled watercolor on paper c. 1898 – 1900 approx. 8 x 10 inches.

Charles A.A. Dellschau (1830 – 1923), untitled watercolor on paper c. 1898 – 1900 approx. 8 x 10 inches.

Charles A.A. Dellschau (1830 – 1923), untitled watercolor on paper c. 1898 – 1900 approx. 8 x 10 inches.

Charles A.A. Dellschau (1830 – 1923), untitled watercolor on paper c. 1898 – 1900 approx. 8 x 10 inches.

Charles A.A. Dellschau (1830 – 1923), untitled watercolor on paper c. 1898 – 1900 approx. 8 x 10 inches.

Charles A.A. Dellschau (1830 – 1923), untitled watercolor on paper c. 1898 – 1900 approx. 8 x 10 inches.

Charles A.A. Dellschau (1830 – 1923), untitled watercolor on paper c. 1898 – 1900 approx. 8 x 10 inches.

Charles A.A. Dellschau (1830 – 1923), untitled watercolor on paper c. 1898 – 1900 approx. 8 x 10 inches.

Charles A.A. Dellschau (1830 – 1923), untitled watercolor on paper c. 1898 – 1900 approx. 8 x 10 inches.

Charles A.A. Dellschau (1830 – 1923), untitled watercolor on paper c. 1898 – 1900 approx. 8 x 10 inches.

Charles A.A. Dellschau (1830 – 1923), untitled watercolor on paper c. 1898 – 1900 approx. 8 x 10 inches.

Charles A.A. Dellschau (1830 – 1923), untitled watercolor on paper c. 1898 – 1900 approx. 8 x 10 inches.

Charles A.A. Dellschau (1830 – 1923), untitled watercolor on paper c. 1898 – 1900 approx. 8 x 10 inches.

Charles A.A. Dellschau (1830 – 1923), untitled watercolor on paper c. 1898 – 1900 approx. 8 x 10 inches.

Charles A.A. Dellschau (1830 – 1923), untitled watercolor on paper c. 1898 – 1900 approx. 8 x 10 inches.

Charles A.A. Dellschau (1830 – 1923), untitled watercolor on paper c. 1907 - 1922 approx. assorted sized approx 15 - 17 inches wide