August 3 - November 3 2019

March 5 - 8 2020 New York NY

|

|

|

|

"An Empathic Gonzo Favola" by Idlu Lili Regulus with quotes from William Mortensen |

|

|

Merely two centuries and twenty-five years separated William Mortensen in time from two of my own ancestors, a witch-mother and witch-father, but unlike them William lived to see old age, they on the other hand instead got executed before their time. One of them was decapitated and the other, still defiant, was singing a psalm as the yearning flames rose on the pyre in which he was burned. Mortensen’s mother and father left their birth-country of Denmark fourteen years before William was born. Many of my relatives as well as a large share of other Scandinavians went on their own exodus of sorts into the brave new world that beyond the vast ocean lay waiting for them in the West. A land beckoning them on with promises of freedom from repressions of every kind, a land of plenty with hills and creeks full of gold, forests and steppes crawling with savages as well as sages, the great wide open just waiting, nay begging, to be claimed or so it was marketed to them. A vast land where one could sow and reap richly, thus assuring their families that they would never again hunger as they had done in Old Europe. My wise-blooded ancestors were alike William’s also born in Denmark. The two lived out their far too short lives there, except for the last decade or so when the place they lived in, or rather the defiant and unruly region called Ránríki/Viken/the province of Bohuslän that they belonged to, passed into the governance and reign of the Swedish crown. This of course in praxis mattered little or nothing to the folks of the time. Most carried on with their doings in peace, like my relatives did on their family farmstead, that is until they were taken into custody and after many hearings and viletorture horrendously executed. I still visit the old family farmstead as often as I can and every now and then also the place where they met their untimely death and ghastly fate. To further create a bridge to our present day I wish to mention the distinguished Clarence John Laughlin, whom I consider carried, and the esteemed Rik Garret that currently carries the torch that Mortensen lit. One could, in this context, argue that certain glory should be bestowed upon the name of Joel Julius Jaenzon that carried out his craft of highly innovative photography art already in 1921 on Victor Sjöström’s film The Phantom Carriage/Körkarlen (literally translated as The Wagoner), based on a novel by the first female recipient of the Noble price in literature, namely the author Selma Lagerlöf. The Phantom Carriage is generally considered to be the first horror movie in the world. In this context it is safest to mention Johan Ankerstjerne’s incredible work on the Swedish-Danish production of Häxan (1922) or Witchcraft Through the Ages. Surely Mortensen must be indebted to the unique images of Häxan (literally translated as The Witch), that Ankerstjerne as a brave, bold and ingenious cinematographer created, in as high degree as to the handicraft of Jaenzon in The Phantom Carriage, or maybe even more so to Häxan.

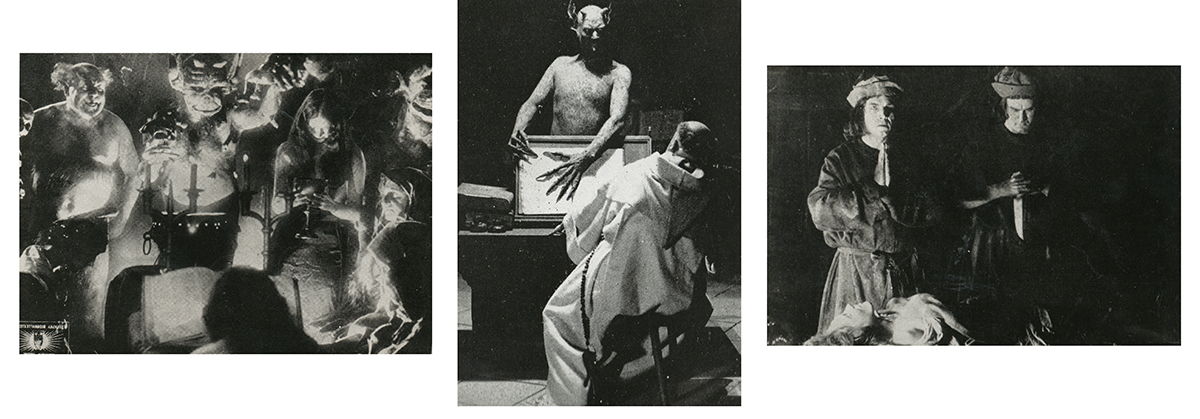

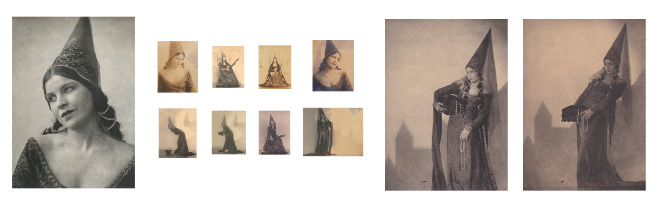

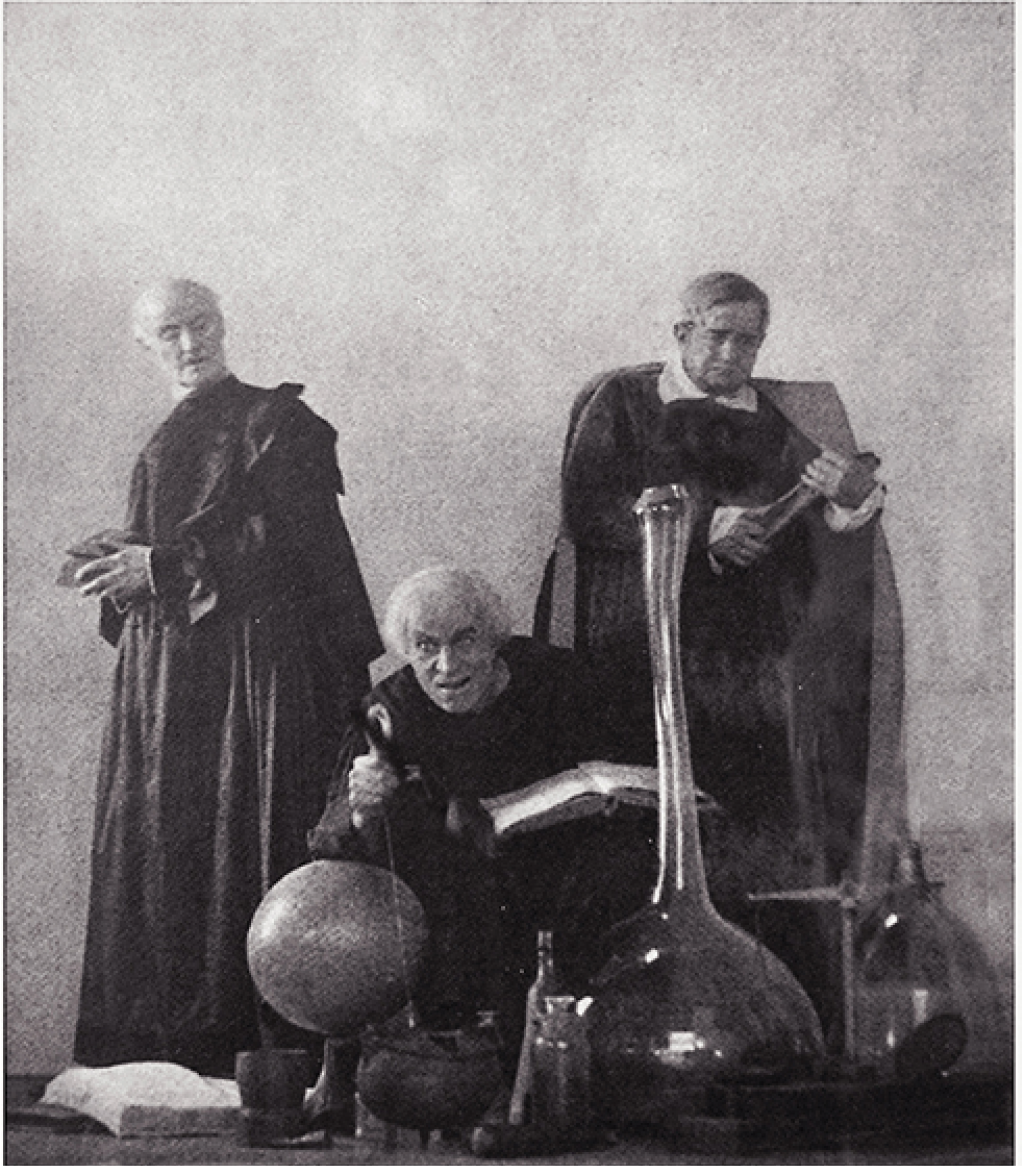

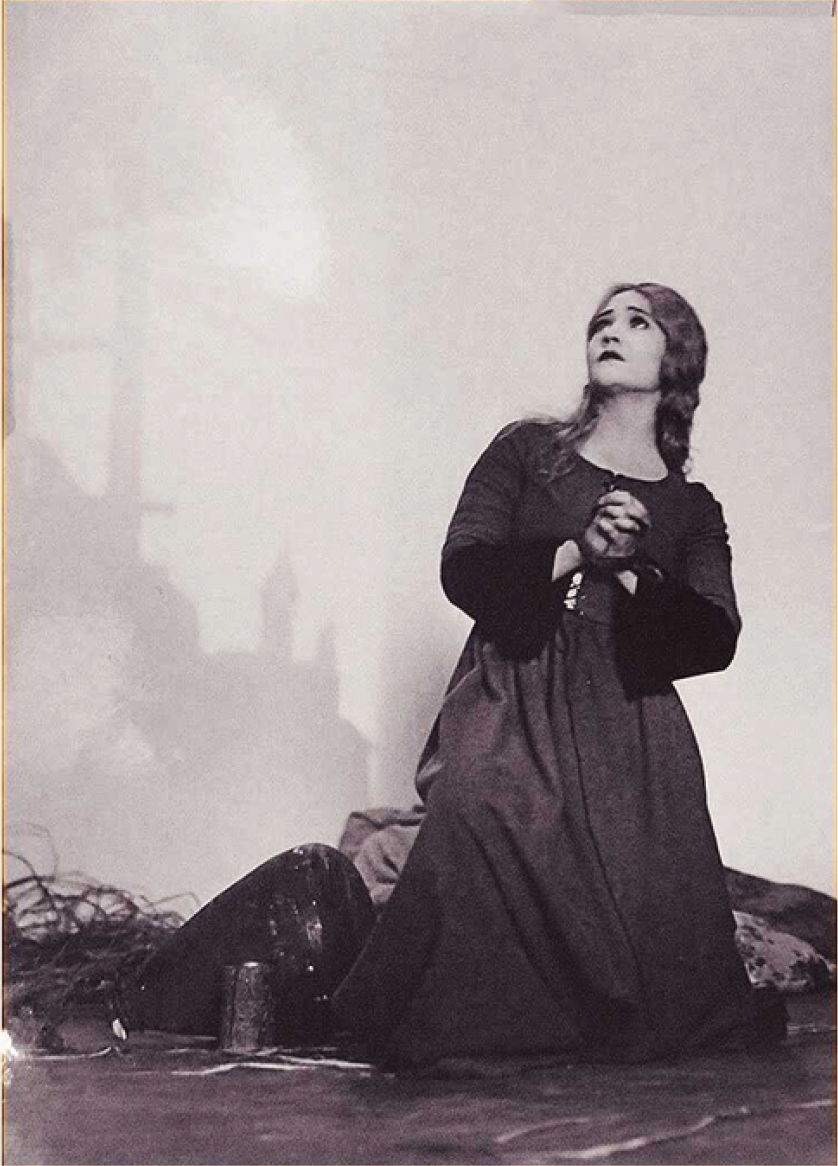

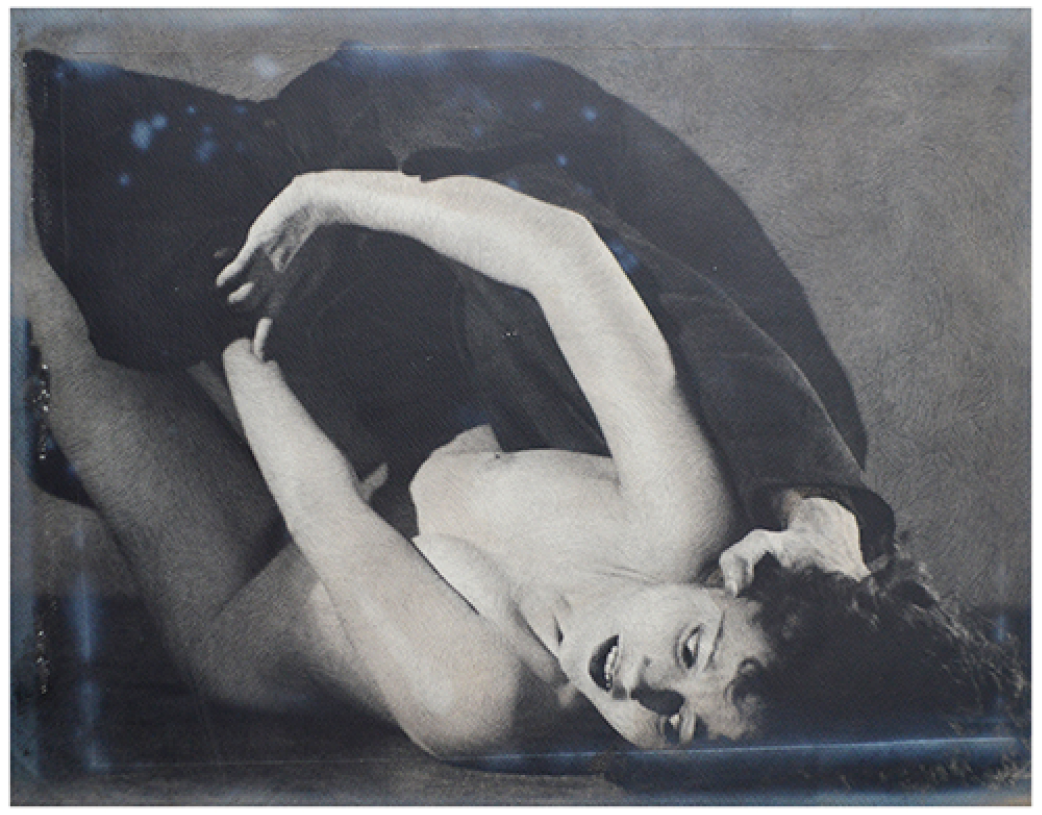

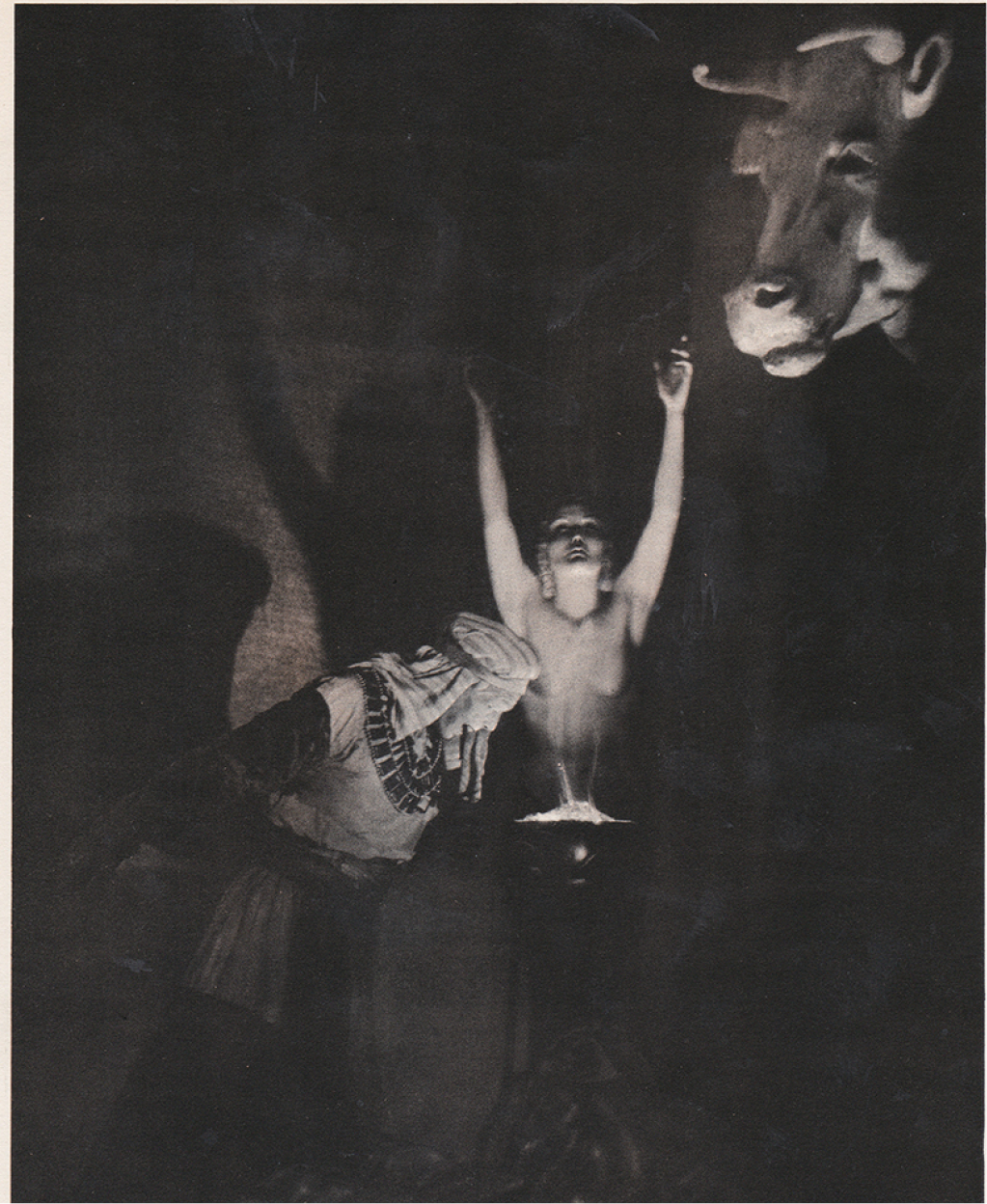

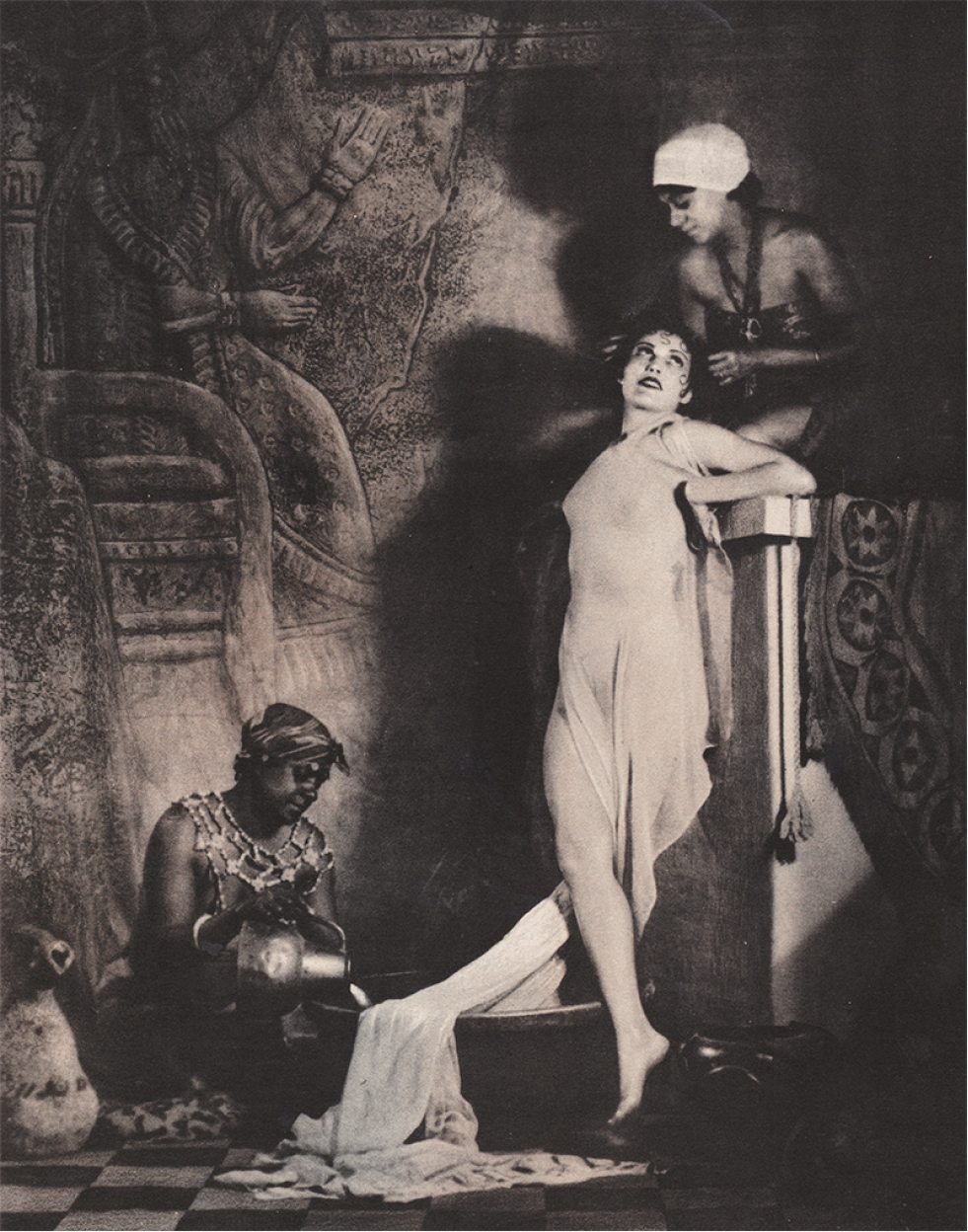

stills from the film "Haxan: Witchcraft Through the Ages" Written and directed by Benjamin Christensen, 1922. collection of Stephen Romano, Brooklyn NY I now wish to address you dear readers and appreciators of Mortensen’s pioneering and trailblazing photographic works of Arte and Art, since probably some of your ancestors, alike my own, were witches. Wise women and cunning men, eccentrics, subversives, freaks or trouble-makers, barefoot dancers and Devil-makers, church-goers, pact-sealers, dream-stealers and Evil Eye revealers. Those blessed with the Second Sight, or just knowing before they opened the door, answered the phone or read a text whom to expect on the other side of the door, the line or whom had authored the received short message service. What you now are reading are my impressions of his art, an empathic gonzo tale of misfits and rejects, about often flat broke humans but never souls with broken spirits. The only things truly broken in this story is the societal view on the Other. For we Are the freaks that lives among you, but you are the ones that are broken as the potshards that were used for ostracizing (from ostrakon) individuals in the days of yore by a condescending and condemning society that treated them and us, for we are one, as contagious criminals, damaged goods and adherents of damned gods. What they failed to realize was that we, the Others, that with open minds, eagerly anticipating eyes and keen senses are the ones in more close contact with nature. For all of these aforementioned aspects and traits are needed to be able to communicate with both Gods, Demons and Angels alike as well as with man and beasts, stones and bones, creeks and hedges, birds and bees and talking snakes in trees. It is these abilities that enable us to find beauty everywhere we turn in the widening gyre of the whole wide whirling world. For in embracing the impure, the dead and the damned we dissolve reductions, revoke dichotomies and just as easily find traces of the One we love in blood as in stone, in flowers as well as in bleached bones, both in fair dresses and ragged fur, truly in all aspects alike just as we adore the Moon in all of her phases and with all her faces of: Maid, Mother and Crone. Mortensen himself was a magician, so am I, but if we leave that literal aspect aside for but a moment or two I will do my best to convey that the great feat of his was in crafting and creating, yes ushering in, an almost supernatural and surreal, real magical realism. Mortensen embodies, not embodied, this really surreal supernatural magical realism, for his legacy lives on and for that we indeed aught to be endlessly grateful. We are also the bearers and perpetuators of this legacy of his, for as long as we love and adore all of his witches, devils, demons, monsters, shunned Madonnas and spirits of sorcery his legacy lives on in each and every one of us! Idlu Lili Regulus, 2019.

"The word "grotesque" is derived from the same root as "grotto." Thus the grotesque art is, in its origin, closely connected with the rites of deities that were worshipped underground. Much of this original significance still clings to it. The old, old fears are still with us, despite the braggadocio of our modern learning. Fundamentally we still fear the winged terrors that hover in the darkness, we shrink from the black mystery of the grave. Herein lies the abiding fascination of grotesque art; for we are inevitably drawn by that which we fear, and cannot take our eyes from that which terrorizes us. There are, however, other motives affecting the use of the grotesque in art. One motive, nearly as old as the basic element of fear, is propitiation. By giving a concrete artistic form to the fear that obsesses us—by giving it a definite time and place, so to speak—we are enabled to lessen its power over us. Another important motive in grotesque art is hatred. There is inevitably a close relationship between hatred and fear. So in dealing with that which we hate, we are very apt to turn to the grotesque. A more sophisticated and modern motive for the grotesque is found in an attitude that we may call "intellectual sadism." The artist, in other words, enjoys the shock that his pictures inflict on his public. This rather trivial motive, I confess, has encouraged me in my indulgence in the grotesque. I take malicious pleasure in observing the horrified reaction of the innocent spectator as he comes unwarned on a picture that strikes past his guard of polite tolerance. A sounder and possibly more dignified motive, and one which contributes much to the modern interest in the grotesque, is the escape which it provides from cramping realism. Realism for its own sake is a blind alley. Photography, owing to the peculiarities of the medium, is made particularly aware of this fact. Photographers who are irked and weary of merely factual reports of everyday people in the everyday world may well turn to the world of the grotesque. When the world of the grotesque is known and appreciated, the real world becomes vastly more significant. We become aware of the dark forces that work behind the curtain of events; the skull suddenly leers at us through the flesh; and we see the exaggerated gesture that lurks behind the most commonplace acts. Edgar Allen Poe in his "Tales of the Grotesque and Arabesque" gave a fresh artistic impetus to the use of such material. Neglected or belittled in his own country, his work created in Europe a new school of literary thought. Many excellent examples of modern grotesque art owe their inspiration to his stories. " - William Mortensen, from “Monsters and Madonnas” 1936 |

|

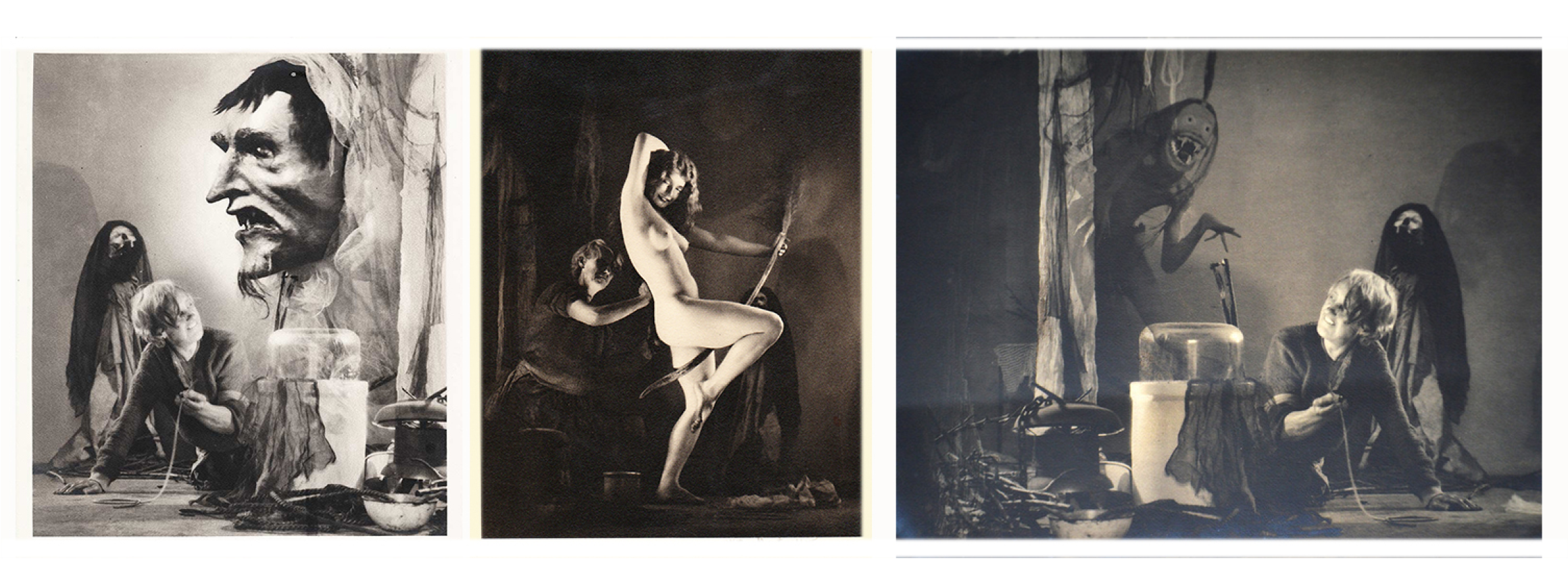

Preparation for the Sabbath Suite 1928

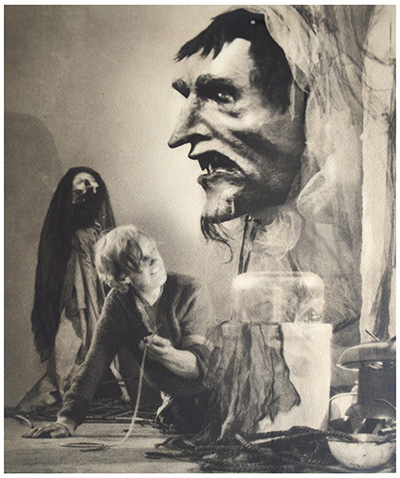

The Old Hag With Mask (1928) in which we behold phials and a cauldron belching smoke as the titanic face of the Lord of the Sabbatic Meadow and Acre of Blood manifest from within the plumes of vapor to proclaim commandments unto the eagerly awaiting witch.

Preparation For The Sabbath (1928) is almost a study of The Departure for the Sabbat by David Teniers, his art is the first thing you see when you open the book ‘The History of Witchcraft and Demonology’ (1926) by Montague Summers. The naked and radiant witch or her astral-form straddles a phallic broom, stalk or ear of Corn. Mayhap the stalk, or the witch herself, is besmeared with the secret secretion of Henbane and Belladonna to aid the lift-off into the Witches Flight towards the eternal black Sabbat. "With this picture we take our leave of the clear open air and conventional understandable themes and plunge into a world of murky shadows and primitive fears. This world is not peopled with the butcher, the baker, the candlestick-maker, nor any of their female relatives, but with the half-glimpsed figures that loom through the mists of our dreams and with troglodytic terrors that reach out toward us across the abyss of centuries. Herein lies the reason for the equivocal effect of grotesque art on many people: the material is unfamiliar, and, by ordinary standards, unpleasant; yet it calls forth a deep instinctive response. Thus they are torn between repulsion and attraction. I have noticed many times that people, coming by chance on a specimen of grotesque art in a gallery, do what the old-time movie directors called a "double take." That is, they pass over the picture with a casual glance, turn away from it, pause suddenly with a startled expression, and then return to it with in-credulous intentness. The subject matter, at first meaningless, suddenly strikes home. Elderly ladies (of both sexes) have often remonstrated with me for upsetting them with such horrid pictures. "The other day I saw such a sweet picture of a little boy blowing bubbles." Yet these same elderly ladies would pause, before leaving the gallery, to further upset themselves with a final glance at the most sanguinary horror that was on view. Everything exists through its opposite. For pictures of calm and tranquil beauty to have any meaning, even. for "sweet" pictures to have any meaning, it is necessary that the grotesque and the distorted exist. Perfection of form is significant only because the malforms exist also. Those who turn away from the grotesque are losing the richness and completeness of artistic experience. A very fruitful field for grotesque art is afforded by the manifestations of witchcraft and demonology. Fear, secrecy, and converse with evil powers, were characteristic elements of this mysterious cult which is as old as man. These elements are of the very substance of the grotesque. The early wood engravers did much with themes derived from witchcraft. Brueghel has worked with this material; so also has Goya; but little has been done with it by photographers. Over-consciousness of the literal limitations of their medium has perhaps held some back from entering this unrealistic and imaginative field. But this very quality of unrealism should be a challenge to a photographer who wishes to pass beyond the conventionally accepted realism of the camera. Some years ago I planned and partly carried out a "Pictorial History of Witchcraft and Demonology." This picture and several others that follow belong to this series. The preparation for the Sabbot has been a favorite and frequent theme of the artists who have dealt with this material. The young witch, eager and exuberant, is being rubbed by the old witch with a magic ointment. By the virtue of this salve, according to tradition, the witches were enabled to fly to their assemblies. Reginald Scot (1584) gives the formula for this ointment or "witch butter" as follows: "The fat of yoong children, and seeth it with water in a brasen vessell, reserving the thickest of that which remaineth boiled in the bottom, which they lay up and keepe, untill occasion serueth to use it. They put hereunto Eleoselinum, Aconitum, Frondes populeas, and Soote." The mysterious setting was assembled from quite commonplace materials. A black background was used, of course. The strange hanging shapes were composed of torn strips of black tarlatan. Dimly seen in the back-ground is a skull, supported on a tripod and draped with a dark cloth. The snake form in the foreground is the hose from a gas heater. Close examination will reveal the fact that my garbage can functioned in this picture also. The curiously curved broomstick, which the young witch bestrides impatiently, was made from a palm branch. The old beldame, the important subordinate character in the composition, was played by the scrub woman who came in that day to clean. Without warning, and without change of costume, she found herself suddenly thrust into a picture. This picture is one of very few in which I have made a successful composition with two figures. Such a com-position usually results in an uncomfortable division of interest. But here there is no such division. The old witch is effectively subordinated, both by her inferior position, and by her lesser illumination. "Those who can't resist new developers might try this formula some time. 1 am sure it is as good as some others.” - William Mortensen, from “Monsters and Madonnas” 1936, on his photograph “Preperation for the Sabbath”

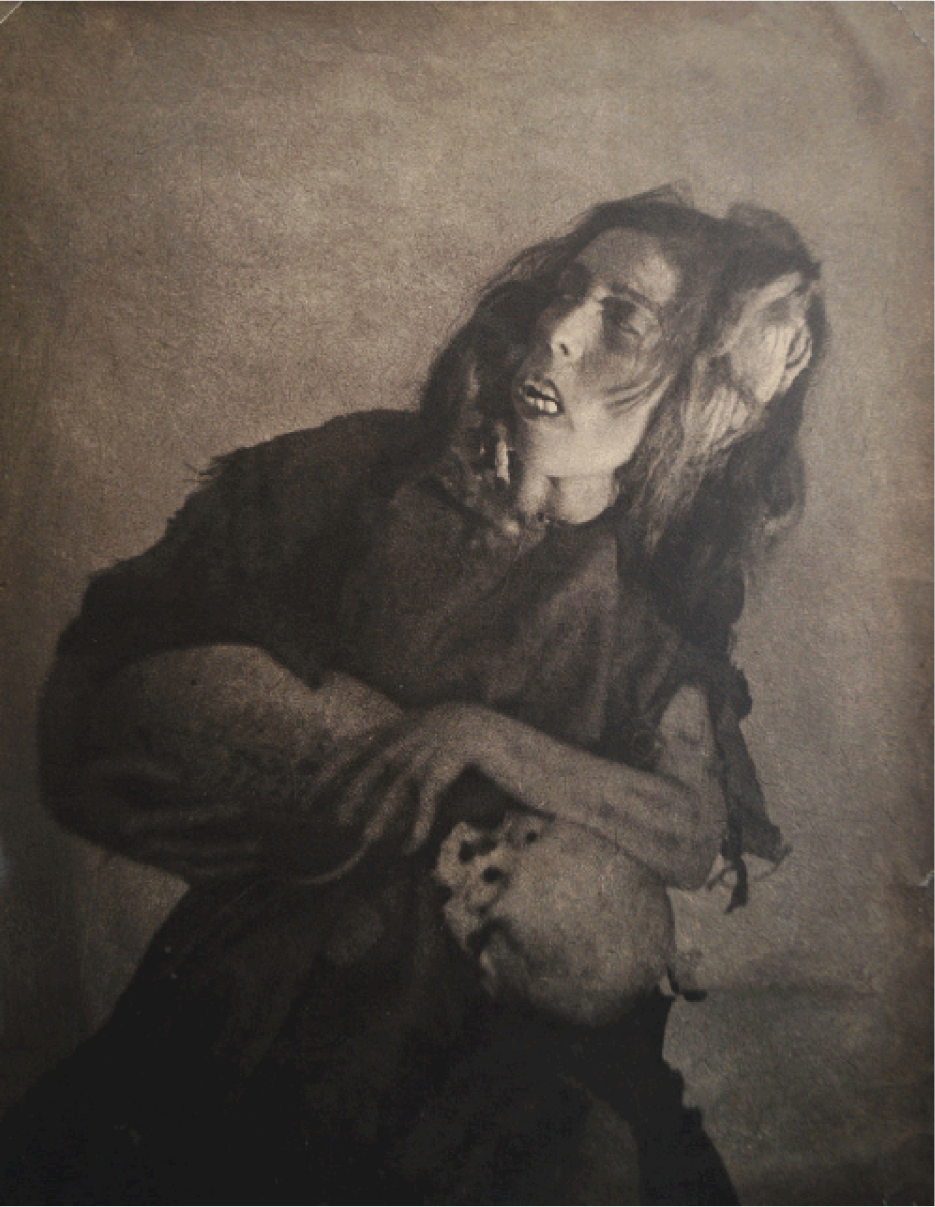

The Old Hag With Incubus (1928) depicting a manifested demonic apparition, entering from the left in the scene. The demon brings tidings of the Sabbatic call for the old crone/mage to attend and pay homage to her dark Lord.

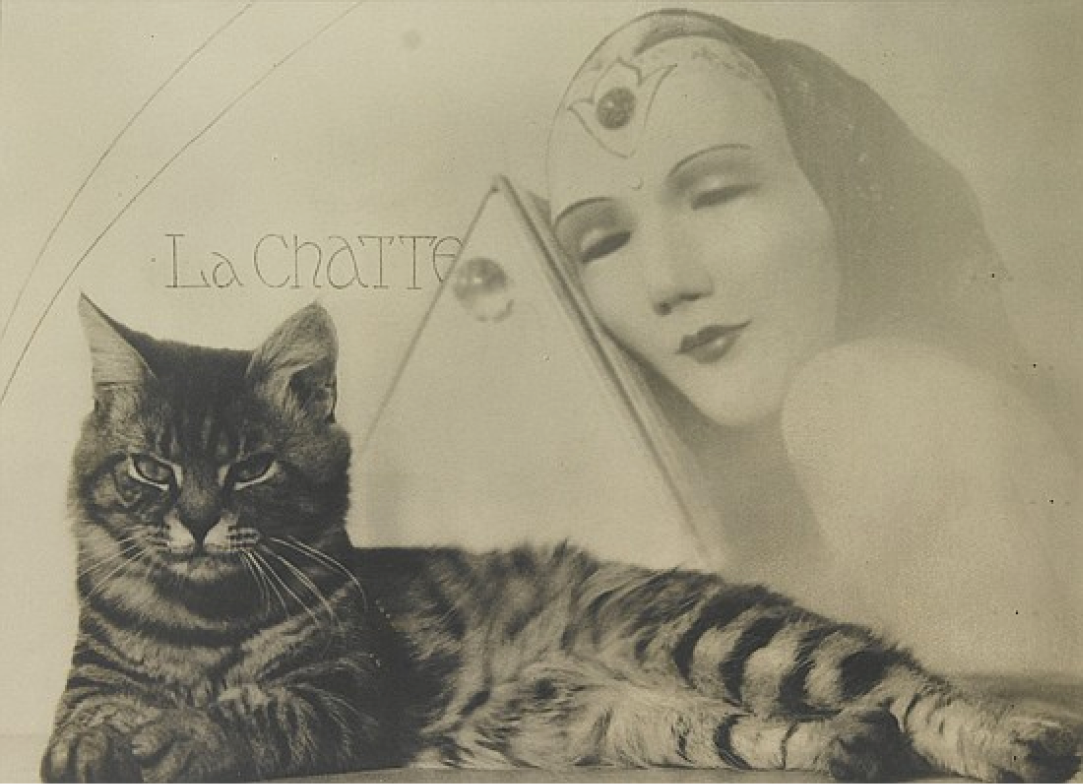

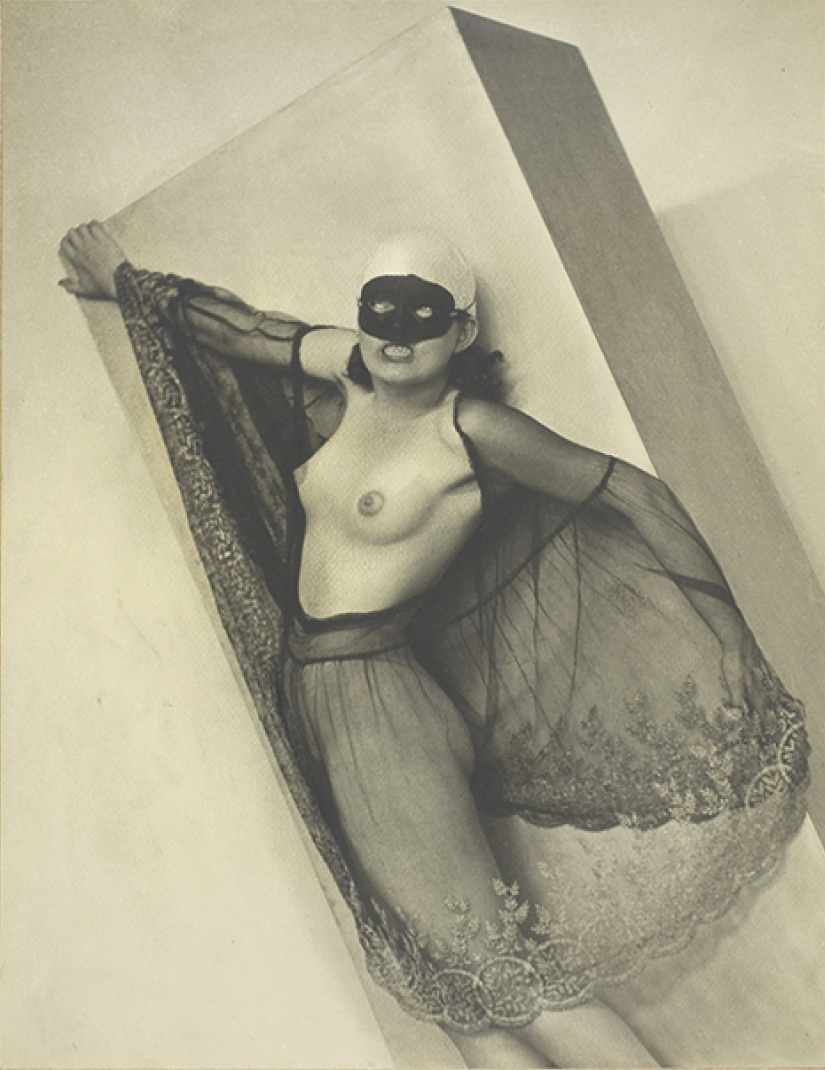

In La Chatte the modus operandi of the witch has been facilitated by the putting on of her mask that both acts as armor and aids a speedy descent into the deep states of trance. Now she freely can travel the astral fields of the world and the worlds beyond and betwixt. As her own eyes closes her third eye opens atop the pyramidion apex in the next world while her other two opens in the ever-watchful calm and firm gaze of her cat, the familiar of yore in the ancient Craft of the Witch.

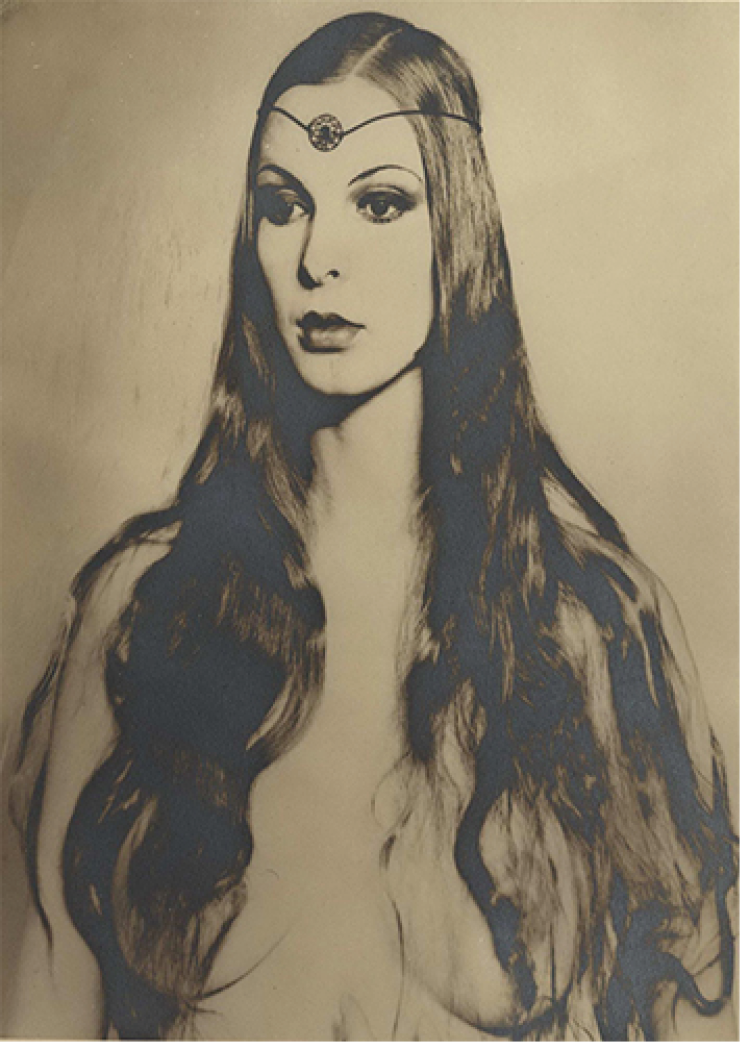

The Witch Lady Suite (Courtney Crawford as Morgan le Fay) 1926

Portrait (1926) to me is the tarot card The Empress. She does not appear to be clothed in the sun, she is the sun, beauty and success attained through her wise and resourceful actions. The pearls round her hair are the stars of the firmament, the golden and copper rings on her headwear the planets and woven into her garment are the wyrd-threads of each soul she will encounter throughout the rich tapestry of her life. Pleasure and joy from her eyes emanate.

In Portrait (1926) her gaze is contemplative, focused inward and downward. Woe unto all when her Medusine traits come into play and she lifts up her eyes to petrify all and unsheathes her blade. Princess of Swords I name her for as Artemis and Minerva she is vigilant and mighty, insightful and wise, verily an amazon aflame. Determination her second name.

Sitting With Lyre (1926) I associate this with the tarot card Queen of Cups but don’t let her coquettish impression mislead you, warmhearted is not dumb, she is as imaginative as she is blessed with poetic skills. Her lyre and inkwell is always at hand as is her prized painters palette.

Sitting With Sword (1926) this work embodies the tarot card Fortitude. Her courage has enthroned her, she wields the power and might, the indomitable strength. Self-possessed she madly backwards dances on a razor’s edge wearing a smile. ‘Per aspera ad Astra’ her credo her gaze firm and fiery.

Portrait 2 (1926) incarnates as the card of The Star, though a tad dreamy she with ease leap the revolving sword of ordeals. In this age she embody Faith, the lodestar that beckons us on. The Star fallen to earth, the laughing Maid that with joyful heart lovingly hands overflowing cups to the cracked lips of ours, the parched pilgrims.

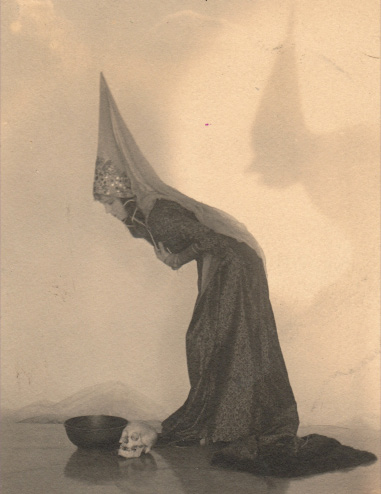

Standing With Scrying Bowl And Skull (1926) iis to me the tarot card The High Priestess. She is change, she is wisdom, she is judgment and decisions sound. She is alteration, she is fluctuation, she is our priestess, the voice of the Divine.

Standing Scrying Bowl And Skull 2 (1926) has been graced with the honour to incarnate the subtle form of the tarot card Temperance. The marriage of forces empyrean and infernal, fire and ice, death and life, young and old, man and woman, shadow and light, body and spirit. The arcane Hieros Gamos of Heaven and Hell, verily the Ceremony of Opposites.

Sitting (1926) with its dreamy imagination brings the card Princess of Cups to mind. She is draped in an airt of a reflective poetic gentleness. She offers insights in matters otherwise obscured, as all potent poetry pregnant with quintessence should.

Portrait (1926) has been given the sad role of the Five of Cups to play in this her very own melodrama called Life. Sorrow and sadness, treachery and deceit, the end of pleasure, the loss of something that once was held very dear. Disappointment found in someone close, here Mars in Scorpio come to the fore. Indeed a heavy burden to bear and mournful role to play.>

Large Standing With Box (1926) I interpret this as the tarot card of the Queen of Pentacles, she is as highly intelligent as she is as melancholic and impetuous. I see here a moody carmine empress as charming as a carmagnole paired with a golden vein of truthfulness, a rare and highly priced gift in our Kali Yuga age.

Large Standing With Box 2 (1926) it is as if our beloved, mischievous and lascivious Naamah herself from Universe B had climbed through her web to manifest here in this work of arte. The Princess of Pentacles, is within this portrait enshrined and embodied.

The Old Hag With Skull And Scrying Bowl (1926). Has there ever been a more potent and portent archetype connected to magic, that old Witchcraft, the horror and awe, than the Crone? I would say no! She is so imprinted within our souls that we sometimes take her for granted. The Old Hag with Skull and Scrying Bowl ties perfectly in with the Crone of yesteryears. May she praised and blessed be.

The Old Hag with Skull (1926) is a vibrant ninety-three years old befit to be a still from The VVitch, Körkarlen/The Phantom Carriage (1921) or Häxan, Witchcraft Through the Ages (1922). The hand-features slightly dissolved lending an airt of avian talons to the Hag. Her eyes slowly open from within the deathlike states of trance. A rabid animal awakens from unnatural sleep with mouth ajar.

The Tantric Priest (1932) with his eyes closed in trance he raises the most potent, wrathful and evocative ritual implement in Vajrayana Buddhism: the Kīla/Phurba knife symbolizing the Karma activity of the Buddha. Crowns as this possess esoteric powers when held in the hands or worn on the head of an initiated priest. The act of wearing such a crown also enshrines the status of the tantric specialists in Nepalese society.

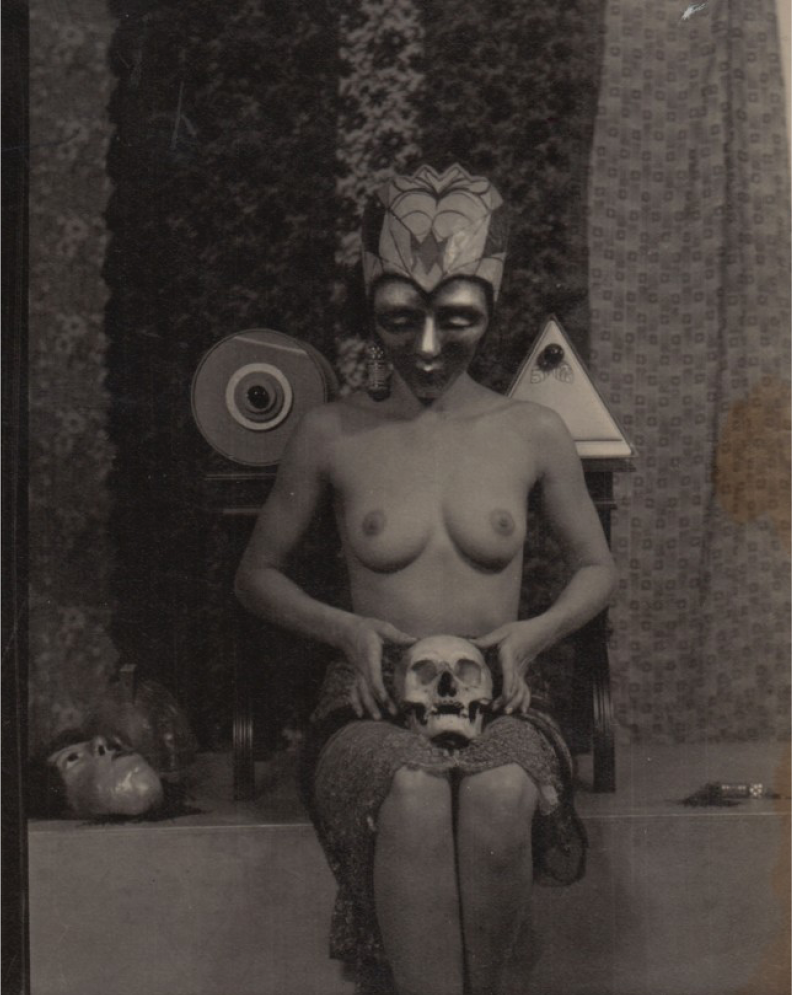

In The Sorceress (1926) we find the archetypes of Goddess, Priestess, Witch and Votaress have formed a merger. A Crossroad nexus, a powerhouse of the sacred, seduction, sensuality and true freedom. The bare-breasted Goddess and/or priestess eternal, forever above the norms and prejudices of the limiting world of men with their petty moral and concepts of sin. The Minoan snake goddess and Pontia Theron figurines race into my mind. She is Night and a storm that I believe in.

Fraternal Practices (1928) is this a male version of the Moirai; Clotho, Lachesis and Atropos, the three Greek goddesses of Fate, or the three Norns of Scandinavian mythology? Or is it the Moon phases triptych of Magicians or of Monks or Alchemists here seen from left to right: the Waxing Moon, Full and Black Moon? For the first appears be inebriated on Solar-potion, the middle fully intoxicated and the last more towards a sober mind or blank slate.

The Heretic (Betty Compton) (1926) is this mournful, somber and pious soul one of the few survivors in Château de Montségur? The castle that since May 1243 had been under attack by 10,000 royal troops because of the freely chosen faith of its inhabitants. Now, March 16th 1244, the end is near, the battle lost, below the mountain castle the wood for the pyre has been erected. Will she renounce her faith and live or voluntarily mount the pyre to perish in flames?

Madame LaFarge (1931) was a rich, free, lavish and successful upper Midwest widow but in 1870 envious rumors said that the obese, old, well-endowed landlady at night magically turned into a young, sensuous girl, that led the Devil to her bedroom and in exchange for fulfilling all his debaucheries the witch of Bemidji would lend his slaves. Her mundane success was attributed to her reign of terror over the Devil’s slaves that worked for her at all hours. When the priest and parishioners stormed the farm to end her reign the young witch died in a heart attack, and as she in agony clutched at her chest screaming she turned old, grey and obese, then caught on fire and perished. This is her portrait.

The Initiation Of A Young Witch (1928) teems with movement, emotions, fear, refusal, confusion, structures, power and status. Rites of Initiation are successive processes guiding participants through a liminal phase, as such they are considered potentially dangerous for both body and mind, even for ones very soul. Yet when undergone a new societal status and consciousness dawns.

Circe (1932) it was said that Hekate herself bore two daughters, Kirke (Circe) and Medea, and a son Aigialeus. Circe lived on Aiaia and was a veritable master of the dark art of necromancy. She called up ghosts using ululatibus, long shrieking, and the aid of her famed and powerful mother.

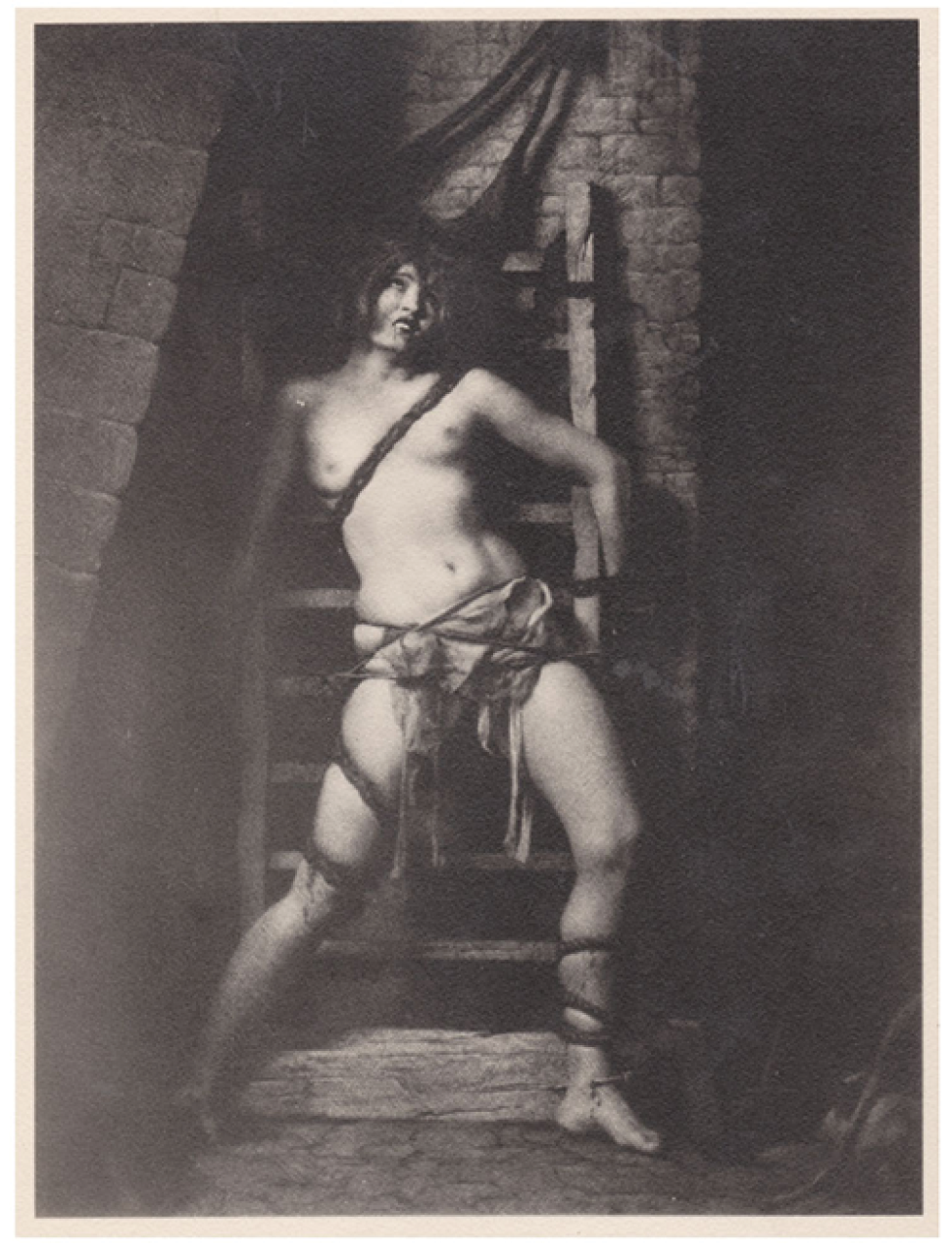

‘Shine clear, Moon: low, in your hushed ears, shall my spells be sung, goddess, and to her, the earth-bound Hecate, before whom the dog- pack cowers when she comes among the tombs for the black blood of corpses. Hail, dread Hecate! Attend us to the close, working direr magic than any Circe worked! ’(The poems of Theocritus, trans. by Anna Rist (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1978), p. 39). "TORTURE and pain are frequent themes of grotesque art. Indeed, it is only in the medium of the grotesque that these powerful primitive motives admissible; for the realistic representation of torture or pain is intolerable pictorially. Like the other phases of grotesque art, the representation of such subjects exerts a tremendous fascination. The attention given to them is shocked, and often unwilling; but it is intense and breathless. This fascination is not reprehensible, nor a sign of complete morbidity. Persons who would be made acutely ill at seeing a dog run over in the street may quite sincerely enjoy contemplating the most brutal themes in the medium of the grotesque. The spectacle of torture strikes through our civilized shell to a primordial impulse of cruelty that lurks in every mortal man. This impulse lies deep and stirs seldom, but it is there. It is not so long ago that public executions were a common spectacle. And we still go to prize fights and wrestling matches. A piece of grotesque art may appeal, in a manner utterly refined and quintessential, to this same impulse. The use of this theme in art is of great antiquity. Assyrian sculptures show torture and execution of prisoners of war. Human sacrifices are depicted in Mayan sculptures. Chinese painters have shown, with great particularity and the most delicate artistry, the method of performing a large number of intricate and clever tortures. Among the first books to issue from the printing presses in the fifteenth century were collections of Lives of the Martyrs, in which woodcuts displayed, in naive and circumstantial detail, the horrible sufferings by stoning, flaying, breaking on the wheel, and boiling in oil whereby they attained to blessedness. Medieval artists delighted also to portray the sufferings of the damned in Hell, serving thereby the laudable twofold purpose of gratifying the righteous and of creating good grotesque art. The torture theme appears frequently in the art of the Middle Ages. certainly the doting care with which Medieval artists lingered over the outraged and multilated body of the Christ was not motivated solely by religious zeal. In times gone by, the most amazing ingenuity of invention and fertility of imagination have been exercised in exploiting the human body's capacity for feeling pain. To the Chinese, torture assumed the delicacy and refinement of an aesthetic problem. In Europe, the tortures were more gross; but, as revealed by the instruments which have survived the thumb screw, the Spanish boot, the Iron Maiden thoroughly effective, and not without imagination. Judicial torture in Europe possibly reached its climax in the period of the Inquisition and the witch trials of the Sixteenth and Seventeenth centuries. The present picture was suggested by the accounts of these trials. When a suspected witch was apprehended (according to the reports) she was stripped, searched and shaved. Her body was carefully examined for unusual marks. If any was found, it constituted presumptive evidence of converse with the Devil. "On the meaner Proselytes the Devil fixes in some secret Part of their Bodies a Mark, as his Seal to know his own by." (Forbes, 1730.) The Devil's Mark is described as being like a flea bite, or sometimes as a "blew Spot" like the impression of "a Hare's foot, or the Foot of a Rat or Spider." Some-times the searchers found supernumerary breasts or "witch paps." These were even more serious evidence. If no marks were found, she was left thus stripped in a cell with a peep hole, through which secret watchers took note of her every action and word. Sometimes under these conditions she would reveal "Stigma" which the searchers had missed; sometimes she would betray herself by incautious conversation with the Devil or her familiars. If the inquisitors still failed to find the evidence they sought or to exact a confession, she was subjected to the additional persuasion of the torture. After being given certain preliminary tortures, she was strung up and given a final opportunity to confess and recant. This is the moment represented in The Heretic. " - William Mortensen, from “Monsters and Madonnas” 1936, on his photograph “THE HETERIC”

The Heretic (1932) it appears as if this poor subversive soul has been victim of The Rack of horrid notoriety. The anguish is tangible, the fear is real, the pain is sharp, the body is aching and the mind begins to wander. Is she conferring with her God? The same God that may have been the reason why she is put here under pain of death? Are she and the unfortunate Cathar-soul we already met sistren? A wife, a sister, a mother, a witch? Does it matter?

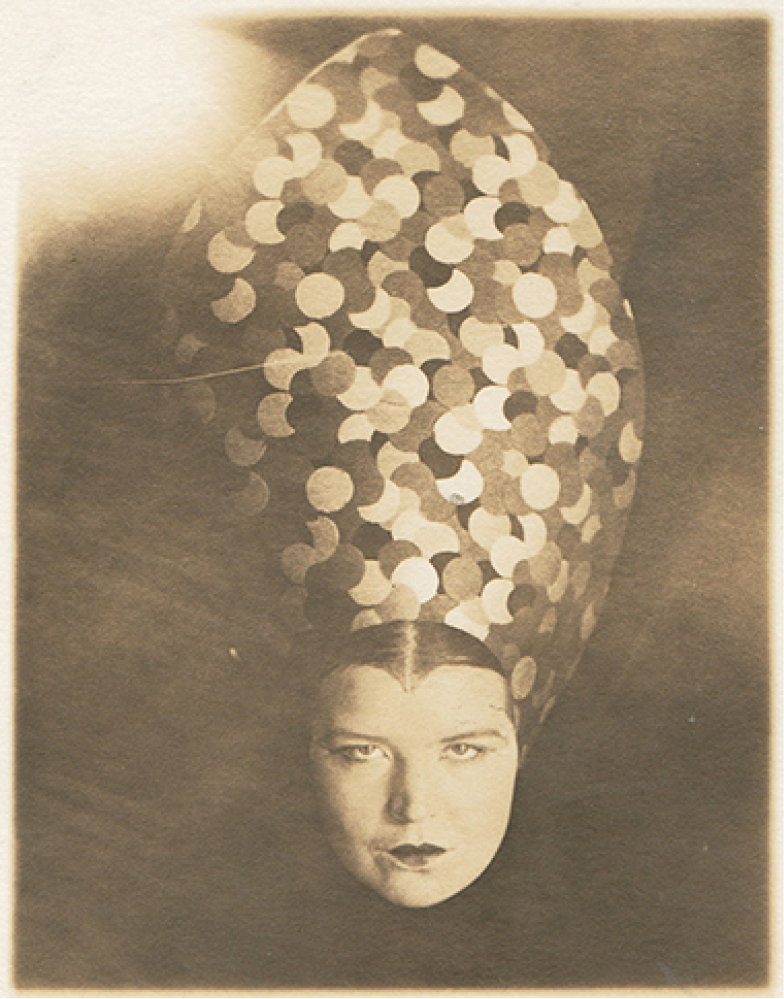

Untitled (Courtney With Headdress) (1926) what is there to say about an artwork to not hinder the imagination of the beholder? It could easily fit on the cover of Vogue Magazine, in a sci-fi novel, in a superhero movie, on stage with the band Ghost, as the image of a wise oracle or why not in a psychotic episode in a David Lynch movie? Only your own imagination sets the limits and I will certainly not limit your imagination dear reader and seeker.

Untitled (Masked Figure With Skull) (1926) the mask worn by the apparition appears as a lovers union between a Tiffany lamp and the Maschinenmensch Futura of Metropolis fame had merged to render a new wise face of man, god and beast made glass, steel and flesh. As if harking from Eyes wide shut or Lucifer Rising the divine creature unifies male and female, man and machine, life and death. S/he is our Figura Bafometi, a Rebis, a divine Androgyne.

Catherine de Medici (The Occult Queen) (1926), all according to a book of a relative of hers, Princess Michael of Kent, drank the urine of pregnant animals, consumed the powdered sexual organs of boars, stags and cats, and mixed many different herbs in her food and wine. She is also said to have made use of charms. Now whether all this was slander or to be attributed to such grains of truth as that the Queen had studied astrology we do not know. "There are certain types who seek the grotesque merely to gain this new shudder. These are the ones who are consumed with that anaemia of the soul, boredom. Their ability to appreciate the quieter sensations has become depleted, and, like drug addicts increasing their dose, they are obliged to seek new and ever more violent sensations. From this group are derived the extremest, most unpleasant, and least productive talents of decadent art. Uncreative, unsatisfied, they arrive at an exclusive and coprolitic devotion to the fruits of the charnel house and the morgue Aside from this enervated boredom which leads to these dreary excesses, there is boredom of another and more vital sort; an active, creative force that leads to accomplishment along new lines. Boredom, with the prosaic material of the everyday world, with the smug limitations of his medium, leads the artist to seek new and more expressive forms. Often this search brings him to the grotesque. The photographer, bored to dis-traction by the banalities of realism and the imperious demands of the Machine, should find grateful re-lease in the exaggerations of grotesque art. The art of the grotesque is not mere morbidity far from it. We do not seek, for example, the purely animal shock of photographing the aftermath of automobile accidents. Such subject matter would be ideal, if mere morbid sensation were the sole aim. But, on the contrary, the thing photographed must have pictorial merit, and, as a grotesque symbol, it must have mean-ing. I have suggested that grotesque art derives its peculiar power from its connection with very primitive human fears and impulses. Most potent among these fears is the great arch-fear, the great mystery of mysteries, death. In grotesque art it is a powerful motive. Indeed, some have suggested that the fear of death is the basic motive of all art, driving men to try to immortalize a little of themselves in material more enduring than the flesh. Common among primitive peoples is the idea of the "dead soul." This "dead soul," according to this belief, was not transported to a land of the dead, but dwelt in or near the corpse. This belief was the original reason for tomb building—to furnish the dead soul with decent shelter. The tomb was probably the world's first architecture. And early religions centered in the tomb. As a result of this belief in the "dead soul" there was an awe and fear of the dead body. The dead soul might be malignant or resentful, and might do harm to the living. Even today, many people experience, in the presence of death, a cold fear that does not admit of rational explanation. In one of his magnificent stories of the Civil War, filled with subtle intimations of horror, Ambrose Bierce tells of such an instance; a young soldier watching alone at night on a dark road, is driven to insane extremity as he becomes obsessed with the idea that a two-day-old corpse fifty feet down the road is slowly creeping toward him through the shadows. " - William Mortensen, from “Monsters and Madonnas” 1936

The Worship Of Isis, The Moon Goddess (1927) evokes a ritual context with the first figure in a noble gown and headdress, is s/he a Pharaoh, Queen, Priestess or Magician? She cast a shadow reminiscent of wings while staring enthralled at the bright white flame from which Isis, the mourning sister and sky-dancing goddess of magic emanates. With arms raised towards her sky she is the epitome of the bare-breasted Goddess eternal.

Jezebel (1926) this composition of Mortensen feels inspired by John Liston Byam Shaw’s famed depiction of her (1896). Mortensen imprint her upon our souls by letting his statuette of flesh have her radiant face adorned by snakes in the forms of the short serpentine locks of hair. It could almost be a scene from the secret brothel of the Republic of Gilead in The Handmaid’s Tale if it was set in another century.

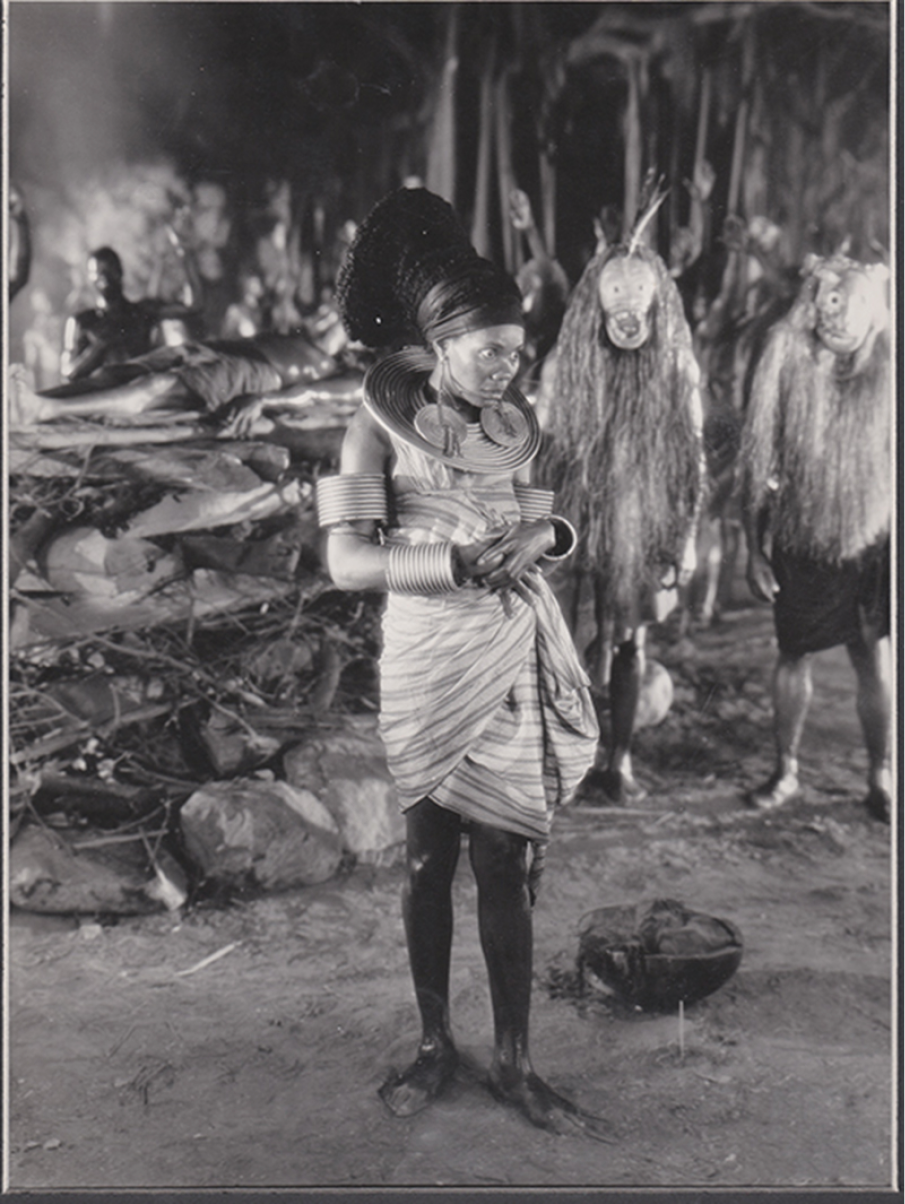

Still From West of Zanzibar (1926), instead of accepting this awful scene of a man’s funeral pyre where his wife or daughter is to be burned alive alongside him I reinterpret it. For this glorious, vibrant artwork overflow with magic, trance, rapture and dance. One can almost hear the drums a’ drumming and the rhythmic, pulsating, hypnotic stomping of feet in the ground, the songs sung aloud, the ancient chanting and the crackling fires.

Ho Ho Off To Sabbath (1926) is nothing short of perfection. Mortensen at the apex of his curve. The naked witch straddles her broom as she darts across a hamlet sky, as if taken from a wood-engraving by Doré, in old Europe towards the black Sabbath. Where does her facial expression stem from? Something she spotted? With the broom stick clasped tightly by her thighs is she in sexual ecstasy or agony? Is her flight backwards? Is she crashing or rising? Close to a century later Laura Palmer in the Black Lodge used hand positions akin to that of our beloved witch. "It is probably true that pictorial art cannot touch so directly the springs of fear as can either the literary art or the cinema. Fear—and the answering thrill of the scalp—is stirred much more subtly, and at the same time much more directly, through the medium of the more primitive sense impressions, touch and smell. Those familiar with the ghost stories of Montague James can testify to this fact. In one memorable story, a man sitting alone in a lamp-lit room senses something stirring beside his chair. Without looking, he puts his hand down; and a soft and hairy mass rises against it. Consider the utter impossibility of adequately rendering this moment in pictorial terms. You can represent the hairy mass, you can represent the hand, you can represent the horrified face of the man; but nothing can represent the searing horror conveyed by the suggested tactual sensation. Fear also can be rendered in terms of the cinema medium. Here the purely pictorial element receives much assistance from the additional stimulus of movement and sound. So in the pictorial art of the grotesque we are not so much concerned with stirring fear, or with representing fear, as with representing symbols of fear. The elements of the horrible in grotesque art seldom frighten us any more; they are well domesticated little horrors, thoroughly housebroke, and of a friendly Nature. The Devil was, of course, the principal deity of the witch cult. But he was attended by a large hierarchy of subsidiary demons: Thaumiel, Adam-Belial, Satharial, Astaroth, Golab, Asmodeus, Belphegor, Baal-Chanan, and Adramalek. There are several curious books—notably Le Dragon Rouge and Le Grand Grimoire—which contain detailed portraits of many of these demons"" - William Mortensen, from “Monsters and Madonnas” 1936

|

|

Stephen Romano Gallery would like to thank J. Kevin O’Rourke, Scott Asen, James Brett, Jillian Slane, Steven Intermill, Idlu Lili Regulus, Alexis Hubshman, Annie Taylor, Toni Rotonda , Jesse Bransford, Barry William Hale and zeroequalstwo.com, Andy Smith and Hi-Fructose Magazine, and Amie Romano.

|